by Jack Fry, KSU

It’s like watching a toddler play with an open staircase nearby. You’re in a good mood and things are going reasonably well, but if you turn your head away for an instant, disaster could strike. It’s no different than managing water on putting greens during midsummer. Minor flaws in greens construction or management may go unnoticed until now; when temperatures are 85 degrees or lower, bentgrass is able to tolerate it. But, an extended stretch of 100+ degree days highs, along with high night temperatures, can bring out the weaknesses in construction or the superintendent’s management program. A rootzone that remains wetter longer can exacerbate problems. Maybe you’re dealing with push-up greens that have been topdressed for years with sand; better than nothing, but not as good as a well-constructed, well-drained profile. Maybe your greens were constructed to “almost” – USGA specifications. For example, maybe sand particle size wasn’t evaluated by a testing lab, pea gravel doesn’t meet specifications, or the rootzone is 8 inches deep on some parts of the green and 15 inches deep in others. Perhaps your topdressing sand particle size distribution, or frequency of application, are different from the previous superintendent. All of these factors can contribute to the rootzone holding too much water, or not enough.

A rootzone that stays wet too long will have limited oxygen, and also be hotter than one that drains well (water helps retain heat); neither situation bodes well for bentgrass roots. Optimum bentgrass root growth occurs at 50 to 65 F. The top two inches of most putting surfaces in full sun during mid-day during July in Kansas will be 90 degrees or higher. Up until now, we have had excessive rainfall, and roots of bentgrass and annual bluegrass on many greens are no deeper than a couple of inches, particularly if the rootzone retains more water than desired. Furthermore, the roots that are there may not be functioning at an optimum level with the ongoing heat. The plant’s water-absorbing capability has been severely limited (it’s like being really thirsty with a cold glass of ice water in front you, but you’re not able to swallow). The “deep and less frequent” strategy for irrigation is not going to be effective when roots are shallow or not effective at taking up water. Instead, match frequency of irrigation to rooting depth, which could mean irrigating at least once a day.

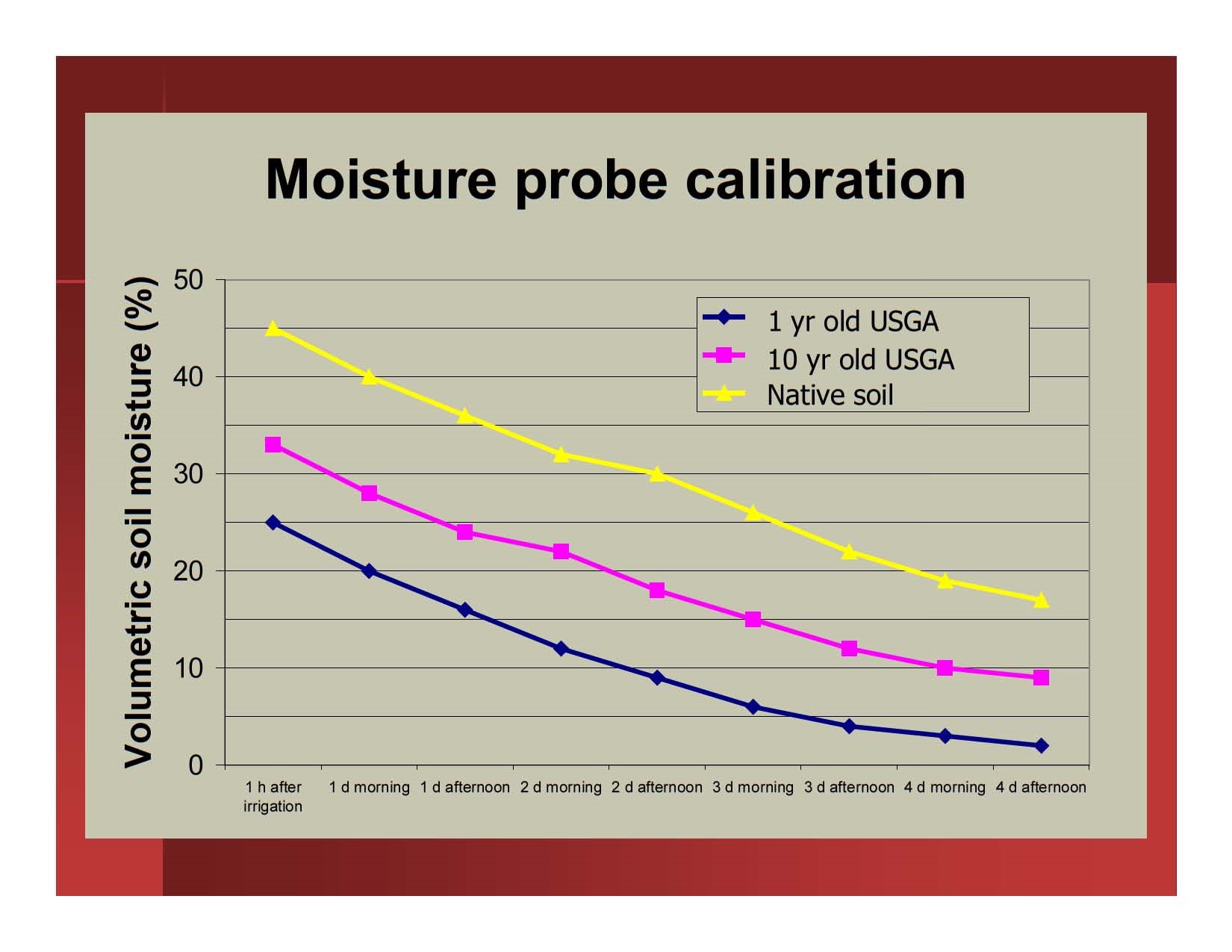

Frequent scouting of greens will help identify areas that are experiencing stress first – the purple/blue color is a good indicator. Lightly watering these areas by hand will help make up for deficiencies in water distribution by the irrigation system and differences in the rate the turf uses water across the surface of the green. Pay particular attention to sloped areas that dry out faster. Hydrophobic localized dry spots will continue to exhibit stress symptoms unless a wetting agent is used in combination with probing the areas to encourage water penetration. The ability to hand water correctly is not something we’re born with – train your best people how to effectively scout and to apply the right amount in the right places. Hand-held soil moisture meters are becoming commonplace for determining volumetric water content of greens (Fig. 1). If you don’t have one, put it on your wish list. By using the probe, you or your employees will be able to identify areas of the greens that are drying faster and need water, or those that are moist enough that watering should be avoided.

Fig. 1. Soil moisture meter for measuring uniformity of rootzone water content across the putting green.

Syringing, supplying a light mist on the surface of the leaves, can be used to help cool the leaf’s surface. However, it’s most effective when the humidity is lower and/or if there is air movement to help the water evaporate. Thin out or remove trees, or install fans, before relying on syringing to get creeping bentgrass through periods of heat stress.

Managing water on greens in midsummer is tricky business. Pay attention, put up a gate, do whatever it takes to keep the toddler away from the staircase.