On a clear night in Burden, gazing at the innumerable twinkling lights in the sky can be overwhelming. As bright as these stars and planets seem, they are millions of lightyears away. Taking that into account, it’s hard to imagine how far the farthest planet in our solar system is.

Growing up on a farm in rural Kansas, Gerald “Eddie” Weigle was able to see the icy dwarf more clearly than most. Now, the entire world can see Pluto in a way that was once imaginable only by the National Aeronautics and Space Administration — NASA to us laymen. Weigle was a part of the NASA project that helped to pluck the planet from the Kuiper Belt and place it in the palm of our hands.

The Burden native’s path to completing contracts for NASA started humbly enough. Weigle went to Burden High School, graduating in 1988. He then attended Southwestern College for his first four years of secondary education but eventually relocated to Manhattan to complete his final four years at Kansas State University, receiving a master’s in electrical engineering. “It wasn’t easy. I was in school for many years. None of that school is what I do now,” Weigle said, chuckling. “Part of it is just being at the right place at the right time. (Another) part is just befriending the right people.” After getting his master’s, Weigle spent 15 years doing hands-on work at the Southwest Research Institute (SwRI) headquarters in San Antonio. Then an opportunity presented itself that would take 10 years to come to fruition.

New Horizons, a NASA-funded program, was going to send a spacecraft to the farthest reaches of the solar system. Pluto was finally going to be seen up close and personal, and NASA wanted Weigle’s expertise to be a part of the mission.

“The biggest fascination to me was that (Pluto) was the great unknown as far as the traditional nine planets. It’s the last planet to have humans fly something by it or on it,” said Weigle. “This is the first time seeing a new world. What’s not to be completely enthusiastic about?”

New Horizons is part of NASA’s New Frontiers Program, which attempts to accomplish specific solar system exploration goals with frequent, medium-class spacecraft missions, according to the New Frontiers website. The New Horizons mission priority was to understand where Pluto and its moons fit in with the rest of the objects in the solar system. The success of the mission would allow the United States to complete the initial reconnaissance of the solar system. Contribution to the project was shared by many teams and organizations, including Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory, Ball Aerospace Corporation, NASA Goddard Space Flight Center and SwRI.

Leading up to launch

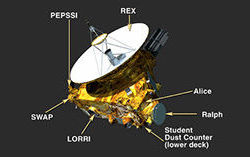

In the years leading up to launch, Weigle was the flight software lead on Ralph, one of the instruments on the New Horizons payload. Ralph, a joint  effort between Ball Aerospace Corporation, NASA Goddard and SwRI, is a visible and infrared imager/spectrometer that provides color, composition and thermal maps for the spacecraft.

effort between Ball Aerospace Corporation, NASA Goddard and SwRI, is a visible and infrared imager/spectrometer that provides color, composition and thermal maps for the spacecraft.

“Any time you see color data from Pluto, the color is coming from the Ralph instrument,” said Cathy Olkin, planetary scientist and one of the principal investigators for New Horizons. “The important thing is that we’re using Ralph to map the composition of the ices on the surface. We can see what’s on the surface and what molecules are making up the surface.”

Despite the small amount of data transferred from New Horizons, Olkin and other scientists have determined there’s a concentration of carbon monoxide ice in the heart-shaped region of the dwarf planet, known as Tombaugh Regio. Ralph assisted in this discovery. The naming of the Ralph instrument stems from American popular culture by working in coordination with another instrument on the payload, Alice. Alice looked at the composition of Pluto’s atmosphere as an ultraviolet spectrometer.

“This is very complementary to what Ralph does because Ralph looks at the composition of ices, the solid surface of Pluto,” said Olkin. In the development stage of the craft, it was decided that the two instruments would be “married.”

“They paid tribute to ‘The Honeymooners,’ so it was Ralph and Alice Kramden because you knew that (the instruments) could be on and taking data at the same time,” said Weigle. “It was kind of funny how they did that.”

After New Horizons launched on Jan. 16, 2006, Weigle stayed involved in the project, switching roles to Ralph’s cognizant engineer.

Watching New Horizons’ progress

“That means I’m looking at the status and health of the instrument,” he said. “All the voltages, temperatures, currents and things like that. (I make) sure that the actual electronics are working correctly.”

Olkin worked with Weigle on Ralph for more than a decade.

“Back before we launched, we would work together during the development phase of the instrument. Then we worked together as New Horizons traveled across the solar system,” she said. “Every year, we would take annual checkup data to see how the instrument was working.”

In addition to being responsible for the instruments, Olkin was involved on the science end of the project as well. “I would help to define the science observations that we would take with that instrument and then make sure they were implemented properly, along with the rest of the Ralph team,” she said.

Olkin enjoyed the partnership that she had with Weigle. “Eddie’s been great to work with,” she said. “He’s really knowledgeable about Ralph, and I think we make a good team.”

Weigle, Olkin and the rest of the hundreds of individuals involved in the New Horizons mission had been working for over a decade for one moment. They would get only one shot at it.

By Pluto

On July 14 , 2015, New Horizons floated by Pluto. “I don’t think it could’ve turned out any better,” said Weigle. “There were a lot of rehearsals, a lot of work that they did to make sure it would be as successful as possible, but you still never know until showtime.”

, 2015, New Horizons floated by Pluto. “I don’t think it could’ve turned out any better,” said Weigle. “There were a lot of rehearsals, a lot of work that they did to make sure it would be as successful as possible, but you still never know until showtime.”

“I was just amazed,” said Olkin. “When we saw the first high-resolution color image, we saw how many different colors are on Pluto. That tells you something about the different terrains (on the planet). It was just astounding.”

New Horizons isn’t the only interplanetary project that Weigle has his hand in. “The Mars rover, I’m active on that right now. There’s a space station project that we delivered about two months ago,” Weigle said. “There’s another one called Osiris Rex that’s going to go chase down an asteroid in a couple years.”

Big Head Endian

Despite all the work he’s done with New Horizons and the Mars rover, Weigle considers starting his company, Big Head Endian, to be one of his biggest, albeit scariest, achievements. “It certainly has felt like an accomplishment to have Big Head Endian alive for a couple years,” he said. “Who knows what the future holds for it.”

Big Head Endian does work similar to what Weigle did for NASA. “It does software engineering. It’s basically the data handling from the very beginning to the very end, all the way from the embedded systems to the data bases to the websites,” he said.

Now that he’s back at home, Weigle doesn’t have much of a work commute. All he has to do is step out into his backyard. “This is headquarters,” he said, gesturing to the large shed that houses all of BHE’s equipment. “We’ve had four or five people working across, but Kendall and I are the only technical employees. We’re the ones that carry the load.”

Eddie W

eigle, founder of Big Head Endian, works at his desk. The BHE headquarters sit right outside his farm home in Burden.

Kendall Kaufman, chief operating officer of Big Head Endian, has known Weigle since their days at K-State. “(Weigle) is one of the hardest workers I’ve known in the 20 years I’ve been involved in the professional engineering field,” Kaufman said. “He’s an impeccable worker. He’s a winner and always has been.”

While Weigle does the majority of the coding, Kaufman’s role involves testing the software by writing scripts and developing test procedures. Weigle and Kaufman have a couple of independent projects housed out of Big Head Endian. “We’re doing some projects on our own that involve programming Android phones and Bluetooth sensor capabilities and combining the two,” said Kaufman. “I also think there’s a possibility for us to help other engineering companies because of our expertise in the systems engineering role.”

Even though it took over a decade for a spacecraft flying 30,000 miles an hour to reach Pluto, Weigle believes that space expansion is fast approaching.

“I’d imagine that in my lifetime, you’ll see buses of people going up (to low orbit) for joyrides. (NASA) has already comme rcialized an aspect of it,” he said. “I think, maybe not in my lifetime, it’s quite possible that you could see the first people go to Mars. That would be a huge, huge step forward. I’m not sure of all the hurdles left that (NASA) has to conquer, but they’re getting fewer.”

Eddie Weigle, founder of Big Head Endian, visits one of the websites related to his Mars rover work. Weigle also had a large involvement in the success of the Ralph instrument on the New Horizons voyage to Pluto. Weigle is a graduate of KSU ECE.

Eddie Weigle, founder of Big Head Endian, visits one of the websites related to his Mars rover work. Weigle also had a large involvement in the success of the Ralph instrument on the New Horizons voyage to Pluto. Weigle is a graduate of KSU ECE.

Great great experience! Man, that was Pluto! No word can express what fell just now… Really speechles. I would love to come back again and again to get more update from you.

http://telkomuniversity.ac.id