–by Dr. Bob Bauernfeind

Recent questions have been received inquiring about the annoying “miller moths”. Also, numbers of moth captures in my (at home) blacklight trap have picked up

What are they? Why so many? What can I do about them?

“Miller moth” is an all-inclusive umbrella term used to describe any plain brown drab moth. Because virtually all moth species have wings covered with scales, those scales are fluffed off like dust-in-the-air (as dust associated with flour milling plants). At this time of year, the “miller moths” of note are army cutworm moths, Euxoa auxillaris.

Upon close examination, army cutworm moths definitely are not plain, brown or drab. There are 5 morphological forms (called varieties) of army cutworm moths. Each possesses its own intricate and distinctive wing pattern. Adding more to the visual array, brown forms of each variety are males, whereas grayish individuals are females.

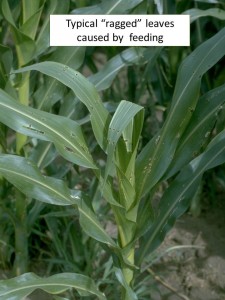

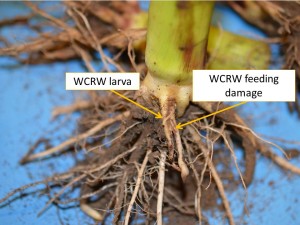

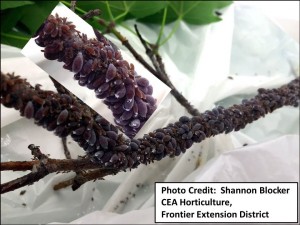

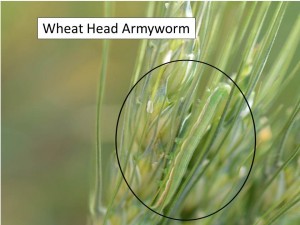

The seasonal life history begins in the fall of the year when moths deposit eggs in the soil in fields of fall-seeded wheat, alfalfa stands and weedy fields/patches. Eggs may hatch within several days of being deposited, but may be delayed under unfavorable/dry conditions. Larvae preferably feed during the dark of night, and seek shelter in the soil during daytime hours. Army cutworms overwinter as partially grown larvae (red rectangle).

Each year in the central plains states, overwintered army cutworm larvae resume their feeding as temperatures moderate/become warmer. They complete their development towards the beginning of May, after which they burrow into the ground where they create protective earthen cocoons inside of which they pupate.

Moth emergence usually begins by late May. Although moths are the mature form of the army cutworm, at this point in time, they are not sexually mature. For a period of time, moths remain near areas where they emerged. Then an undefined stimulus (likely photoperiod driven) signals moths across the central plains states to migrate westward to the higher elevations in the Rockies. There in the cool-of-summer, they feed, accumulate body fat and attain sexual maturity. In mid- to late September, they migrate back to the central plains where they deposit eggs (as previously described) to initiate the next generation of army cutworms.

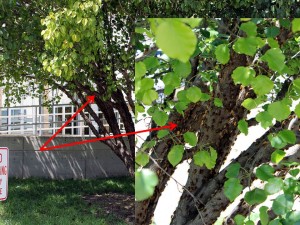

The current complaints revolve around the moths. Again, because moths are active during evening hours, they shun daylight. That is, with the approach of daylight, army cutworm moths seek shelter/cover in any conceivable space. Excluding moths is difficult because they will exploit very small openings. Because garage doors seldom are tight fitting, when one opens the garage door, a flurry of moths may rush out. A car window left open overnight provides an attractive entry point – and when one gets ready to drive to work, he/she will be greeted by a flurry of excited moths. Open a polycart to deposit a trash bag and you may be greeted by a rush of moths. Take an early morning walk and as you pass a line of shrubs, you may be startled by hundreds of excited moths darting out. And so on. In homes, catch or swat a moth on your wall or curtains/sheers and you will find a coating of “dust” (wing scales) left behind.

An example of the “dust” produced by army cutworm moths can be seen where moths gathered from a single blacklight trap are dumped out of a garbage can. Talk about being up-to-your-neck in army cutworm moths!

Another interesting tidbit about army cutworm moths: food for grizzly bears. During summer months, bears move to the higher elevations to feast on army cutworm moths. It was determined that single moth possesses ½ calorie of fat content. It was further estimated that a bear obtains 20,000 calories of fat on a daily basis by consuming 40,000 moths per day.