–by Dr. Bob Bauernfeind

One of my favorite most succinct introductory slides simply says:

While attentiveness, care and pampering are especially important in the early years after newly transplanted trees first become “family members”, there does come a point-in-time when they become “Big Boys and Girls”. Look at mature trees lining city streets, in park and recreation areas and in the countryside —- all thriving on their own. This despite having to contend with different insect pests.

Most alarming for homeowners is the compromised appearance of trees when foliar feeding species come-to-town. The situation is such that their presence first becomes apparent (after-the-fact) when the offending species are approaching the end of their feeding phase-of-development — a time at which they are of such size that they ravenously feed on and rapidly deplete available foliage thus drawing attention to their presence.

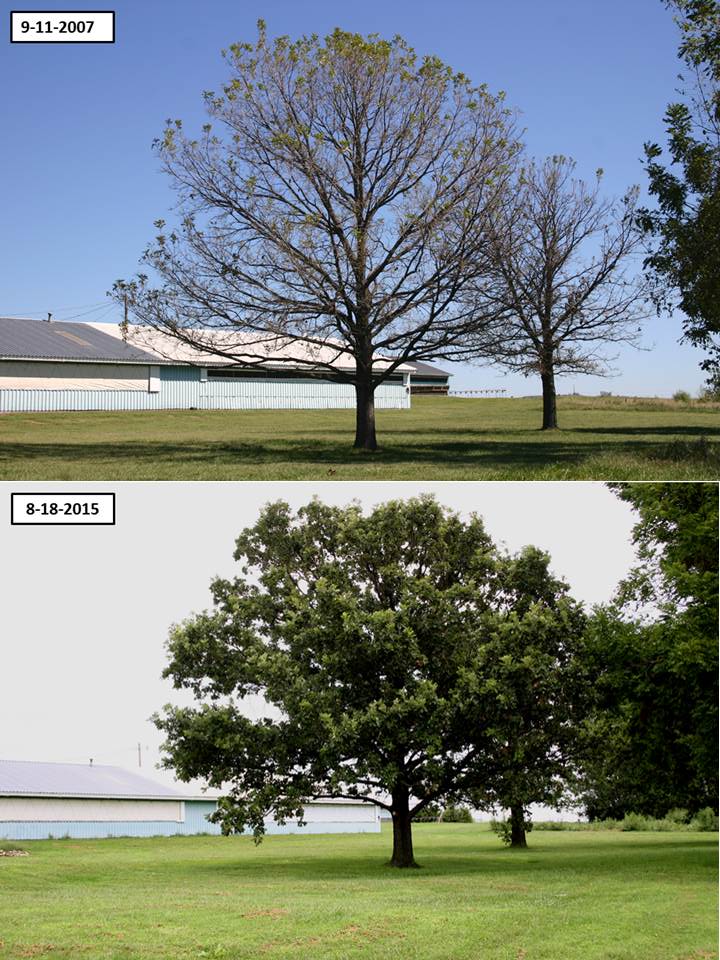

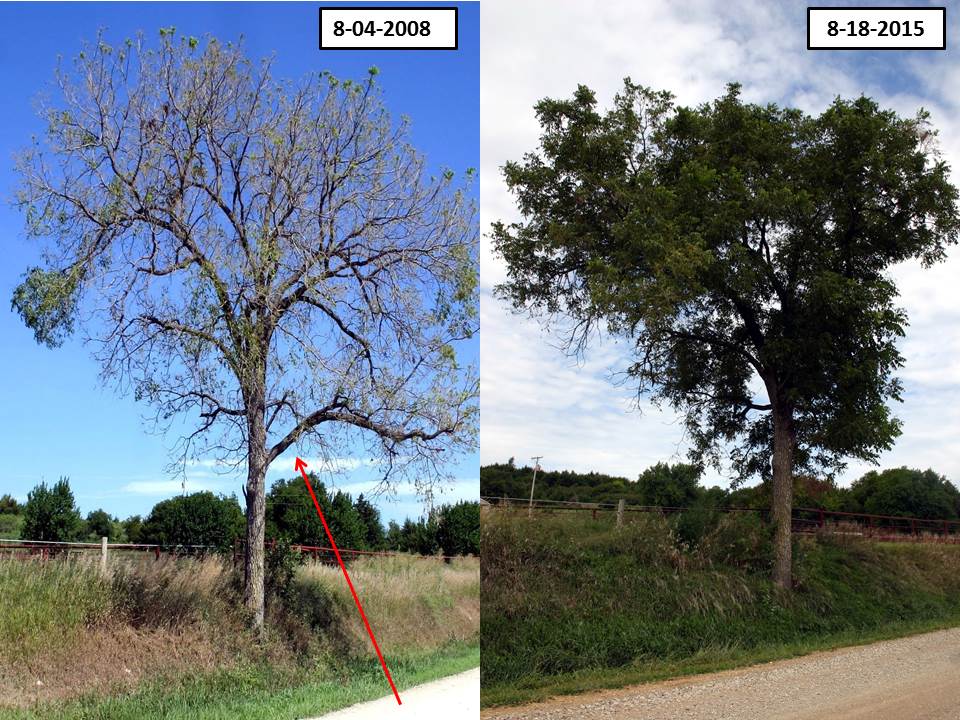

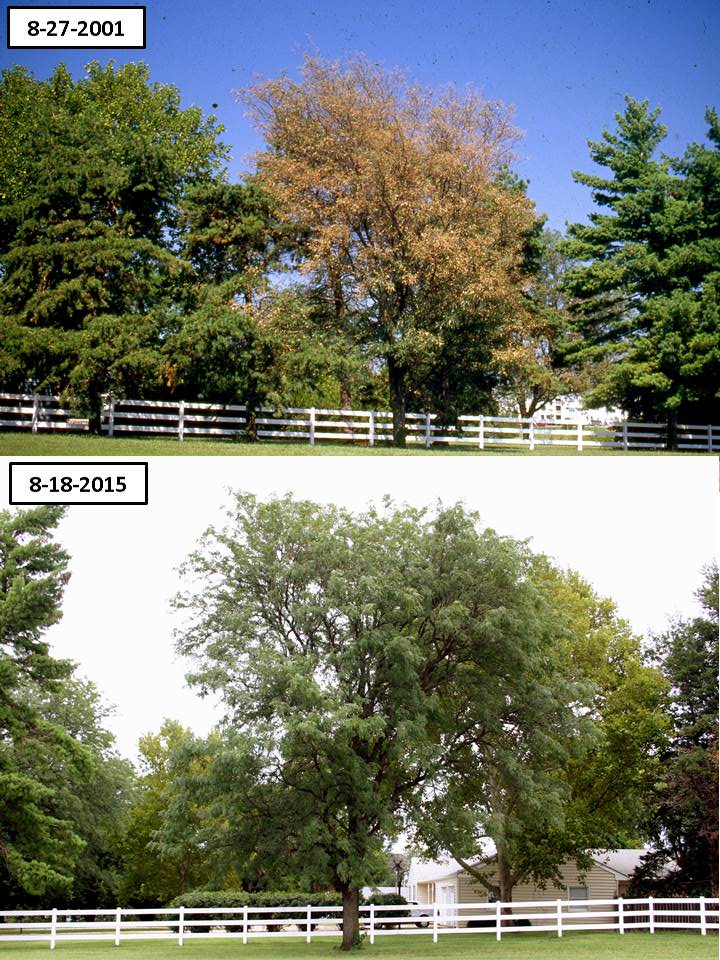

Defoliations may vary in intensity from a few bare branches to the entire canopy. As alarming as a complete defoliation might appear, it should be regarded as but a cosmetic issue. Probably more objectionable is the visible and audible “rain-of-frass”, as well as streams of descended mature larvae roaming about in search of pupation sites. Early-season defoliations are of temporary duration because trees rapidly produce a new flush of growth restoring normalcy. On the other hand, new foliage production is scant late in the season at a time when leaf abscission is imminent after the cessation of seasonal photosynthetic activities. Come springtime, trees again will fully leaf out — seemingly none the worse-for-wear.

People may ask, “What did I do wrong? Couldn’t I have prevented this?”, to which I would respond, “You did nothing wrong. Outbreaks are unpredictable!”. As mentioned earlier, a person is unaware of the presence of specific pests which (as “wee ones”) scrape and nibble away not producing any noticeable foliar damage to give away their presence.

Come the questions, (1) “Well, once I notice the damage, shouldn’t I spray?”, to which there is not an absolute response. Consider the size (and possibly) number of trees, and the unlikely capability of an individual to apply/achieve thorough spray coverage. (2) “Well couldn’t I hire a service to spray for me?”, to which the response might be, “If the service provider is “booked” and unable to get to your tree(s) in a timely fashion, by the time they do arrive, caterpillars/larvae may have already completed and ceased feeding —- little point in spraying at that point.

Balancing the cost of hiring a spray service against what-is-to-be-gained by spraying at a time that tree appearance has already been compromised may make the decision to be to simply allow the situation to run its course.

“Is there a need to “kill-them-now” to prevent a repeat?” While this seems to be a logical thought, in reality, we really have little control over future events. Nature sort of has its own checks-and-balances. Whether unfavorable environmental conditions or biological entities (diseases, predators, parasites) reduce or eliminate potential future “seed” for pest populations, or, if pests themselves naturally disperse, one may never again experience a repeat situation. Individuals who have experienced defoliations and who have seen their trees recover are convinced of the need to let nature run-its-course.

Defoliations: before and after

Greenstriped Mapleworms on silver maples

Yellownecked Caterpillars on oak

Walnut Caterpillars on black walnut (red arrow = limb pruned out in 2011)

Foliar Dessication: Before and After

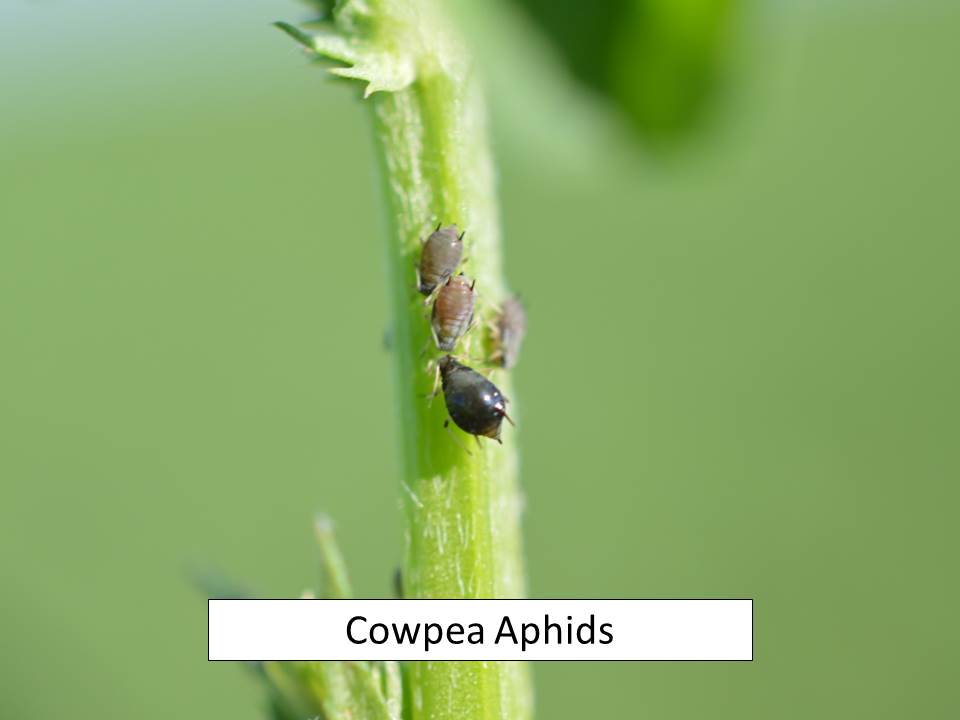

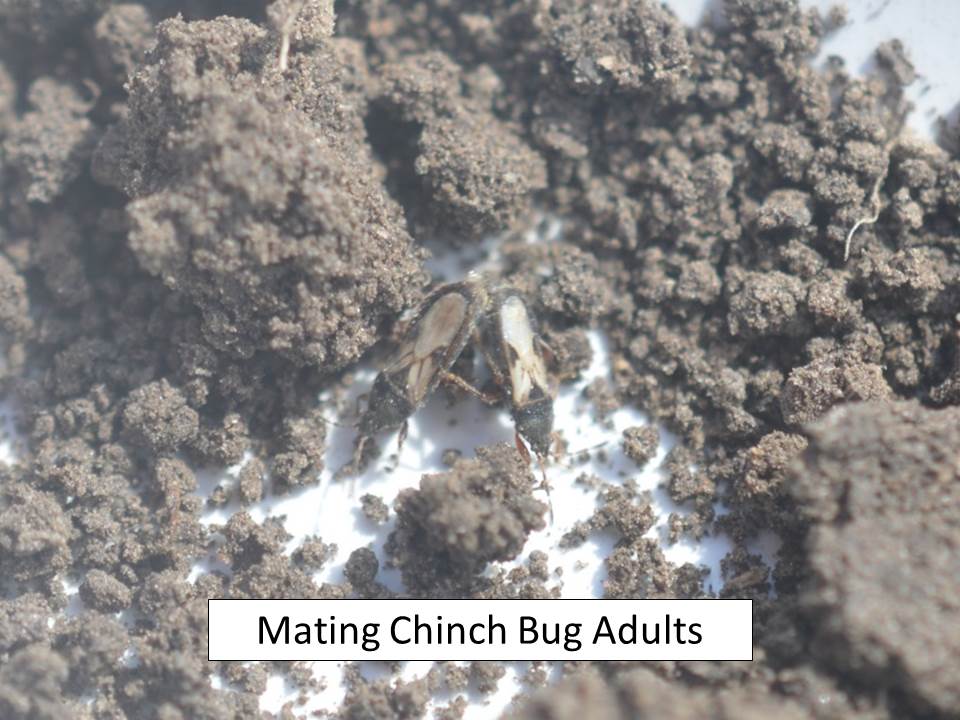

Some foliar-feeders are relatively small in size and therefore incapable of skelotinizing and defoliating tree hosts. Rather, their feeding activities are reduced to nibbling/consuming the epidermal tissues of leaves. Both the upper and lower epidermis (with their thicker “waxy” cuticles) protect the more delicate inbetween high-in-moisture-content internal cellular layers. Deprived of their protective outer layer, leaf dessication leads to leaf death — the resultant being the unsightly browned/burnt appearance of trees.

Mimosa Webworms on honey locust

Elm Leaf Beetles on elm

In this incidence, I do not have a current image of the trees above. They no longer exist. However, not due to to the depredations of elm leaf beetles. Rather, simply, they were in the way of progress. A highway expansion project necessitated their removal. They were no match against “man”. Soooo painful to watch trees ripped out roots-and-all by powerful excavating equipment. But again, the lesson being that the asthetically unacceptable foliar appearances resulting from insect activities are but an occasional temporary fleeting occurrences …. leading to the following:

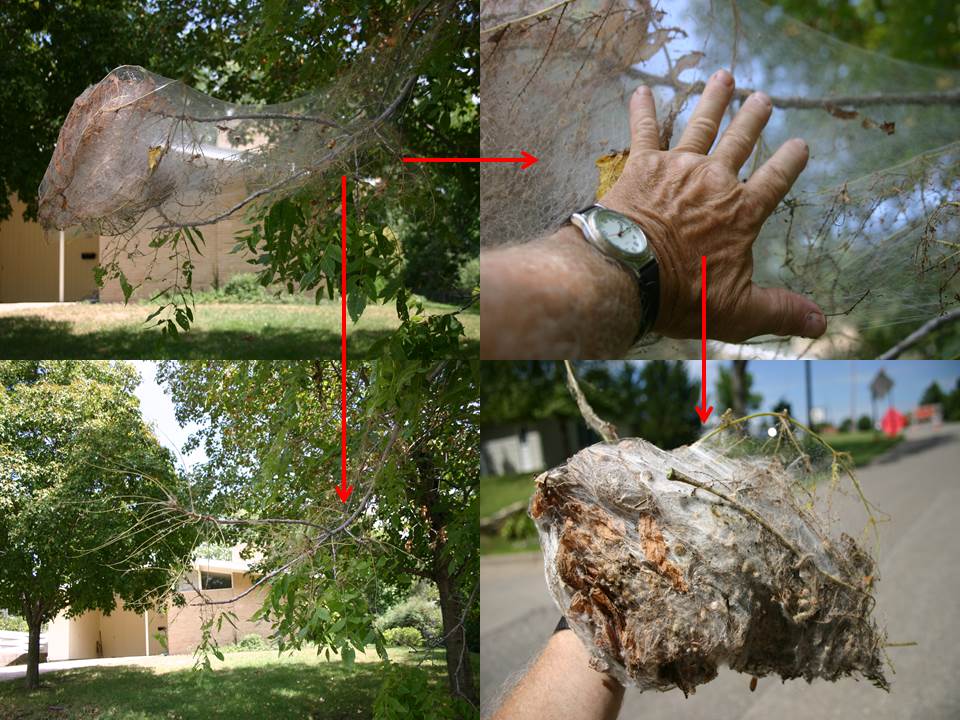

On a return trip to Manhattan Monday, I noted the presence of fall webworms along the roadway — sometimes one or two in an occasional tree here and there, or (in this instance) numerous web masses.

These did not develop “overnight” Judging by their size, these colonies likely were initiated 4-5 weeks earlier. Again under the banner of defoliators, people may worry about the impact of feeding depredations. Minimal! Probably a more verbally expressed concern is the unsightlyness created by the webbing, as well “creepy” clumps of caterpillars within.

A common recommendation is to prune out webbed branches. One must consider the accessibility of web masses — those beyond reach simply allowed to remain.

Pruning might be doable if just a branch or two —- but possibly unacceptable and disfiguring when trees are heavily infested with web masses.

If within reach, consider an implement (of sorts) to “rake out”/remove webbing. And what implement could be more handy (yes, pun intended) than one’s own hand. There is no need to fear the dry webbing and/or dried fecal deposits and squirmy caterpillers within. As webbing is removed, also removed will be the objectionable dead/dry foliage and the fallwebworms. Simply dispose of the gathered material. All that is left behind is the leafless (but still living) branch and it’s intact buds which will produce the ensuing year’s foliage.