Katie Kingery-Page is an assistant professor of landscape architecture at Kansas State University. Kingery-Page has studied sculpture, art theory, ecology, and landscape architecture in the United States and Brazil. Her design work includes streetscapes, school yards, and stormwater meadows. Kingery-Page is focused upon art as a mode of knowledge for landscape architects, meaning both humanities research and design as a conceptual art practice.

Living in northeast Kansas can be a constant aesthetic and intellectual experience with the Flint Hills. The tallgrass prairie landscape of the Flint Hills is rare, globally-speaking, and is both challenging and satisfying, aesthetically. The Flint Hills (and indeed other grasslands) challenge conventional wisdom regarding landscape aesthetics. For decades, professional evaluation of a landscape’s scenic value (such as that conducted by the National Forest Service) has been based upon notions of diverse visual experiences.

Quoting the Forest Service Manual, a “Class A” landscape scores high in the “…visual perception attributes of variety, unity, vividness, intactness, coherence, mystery, uniqueness, harmony, balance, and pattern.” While “variety” and “vividness” in landscape scenes may work very well as criteria for evaluating forest, mountain or seaside landscape, I argue that these criteria are inherently less relevant to the aesthetics of the Flint Hills. The Flint Hills can be understood as scenes of unity, intactness, and subtlety.

When I experience the Flint Hills from a distance (let’s say while driving), it’s the unity of form, texture and color within a single scene that is so compelling. This minimalist landscape aesthetic can be understood through many lenses: the study of 20th century minimalist art; the wabi-sabi aesthetic of Japanese landscape; and even the high lonesome aesthetic of country and bluegrass music. The Beach Museum of Art collection contains work by many artists who capture the minimalism of the Flint Hills grassland, such as Larry W. Schwarm’s Two Hills with Burned Grass, Chase County, Kansas, 1994.

When observing the Flint Hills up-close (the immersive experience of walking through the grassland) what strikes me is the bodily experience of topography and the limitless complexity of tallgrass species which hold in tension visual unity and (yes) variety: look ahead and see a unified sea of grasses and forbs, look down and see the many structures of individual species. This tension of unity and complexity is what my colleagues and I have begun to term “meadow-thinking:” an ability to move seamlessly between the whole and its parts, between detailed concerns and the big picture.

As a native planting designer, I was mentored early in my career by landscape architects, a landscape ecologist, an agronomist, and landscape design professionals. I mention my mentors because I value the informal learning that occurs when designing and building landscapes. The first native plants establishment I designed and helped to install (advised by Dr. Tim Keane and Dr. Clenton Owensby) is a large seeded and plugged landscape near Olathe, Kansas, now in its sixth season of growth. This planted prairie gives a hint of what’s to come in the Meadow.

As the Meadow at K-State lies dormant, just beginning to show its life through sprouts of new grass and wildflower shoots, it’s difficult to visualize the intended aesthetic of the Meadow. Over the next two years, the Meadow’s maintenance regime will require it to be mowed to six inches height. It won’t be until the Meadow’s third growing season that the aesthetic created by plant selection, planting strategy, and path design will be fully visible.

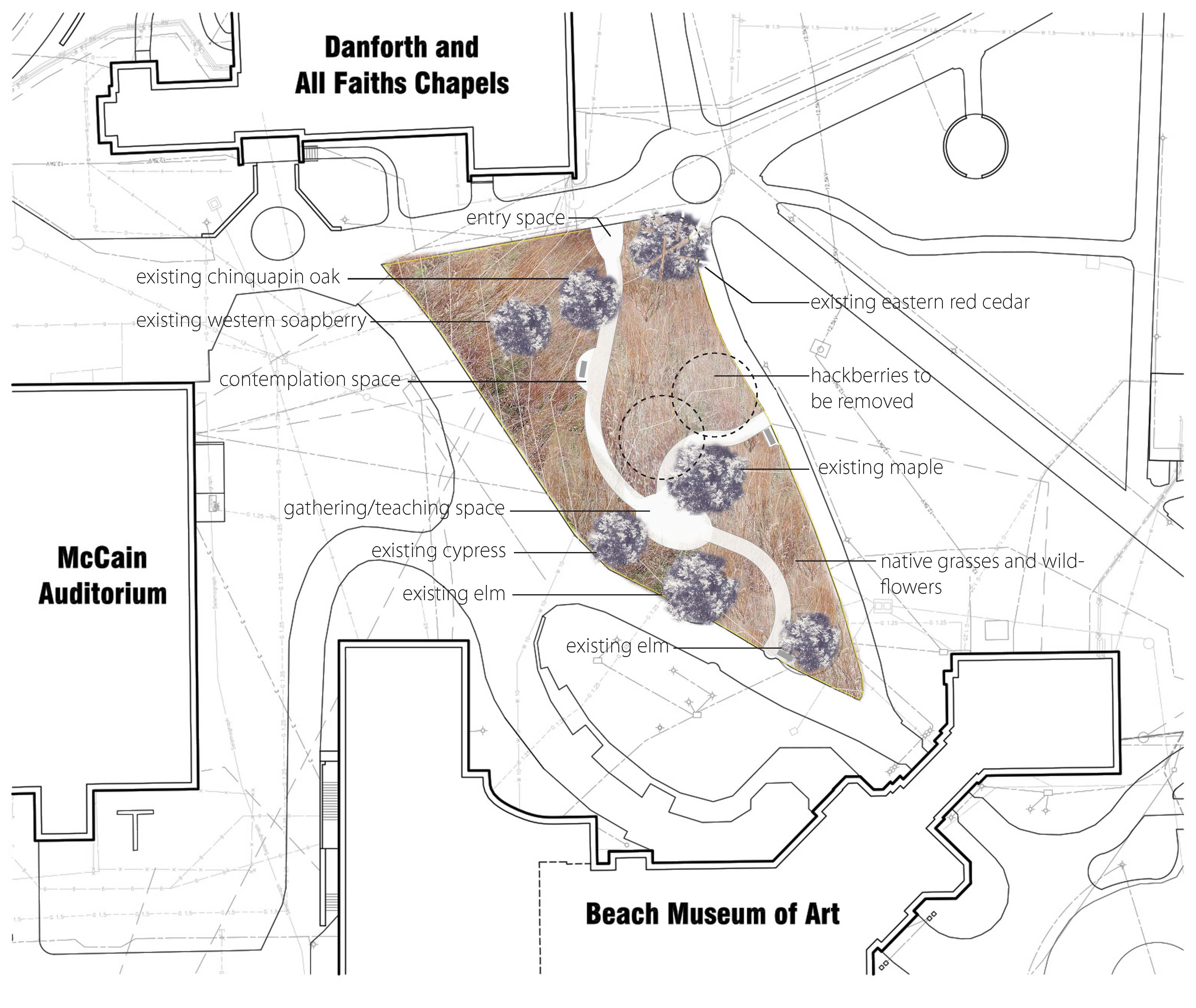

So, I reveal a bit of the aesthetic intent here. The Meadow at K-State (just through the Beach Museum of Art archway) is designed to be a unified landscape fabric of grasses and wildflowers, all less that 40 inches in height. This fabric is incised with a simple system of crushed limestone paths. The path color will contrast strongly with the green, summer growth of the Meadow, but in fall and winter, the effect will soften as the plants mature to tan and rust colors.

Because the Meadow site is relatively small and surrounded by a diverse scene, a simple, unified design seemed best to achieve our goals. These goals include creating a quiet place for restful contemplation and setting the stage for close observation of plants and processes in the Meadow. Aesthetic decisions have been made in context of the Meadow planning team discussions and charrette, considering diverse viewpoints. Many functional, pragmatic factors (which for sake of focus, I have not discussed here) have affected the team’s decisions. Guiding all decisions has been a conscious appreciation of the minimalist landscape aesthetic of the Fint Hills eco-region.