The newest exhibition at Kansas State University’s Marianna Kistler Beach Museum of Art shows how Americans could make fashion — and more — by using bags.

“Thrift Style,” which runs Aug. 1-Dec. 16, explores how feed sacks were reused to make clothing and other household items, particularly during the Great Depression and World War II.

“This exhibition highlights how upcycling — recycling of a discarded item into a product of higher value — of these bags mutually benefited 20th-century consumers and commercial businesses,” said Marla Day, curator of the Historic Costume and Textile Museum, which is a part of the apparel, textiles, and interior design department in the university’s College of Human Ecology.

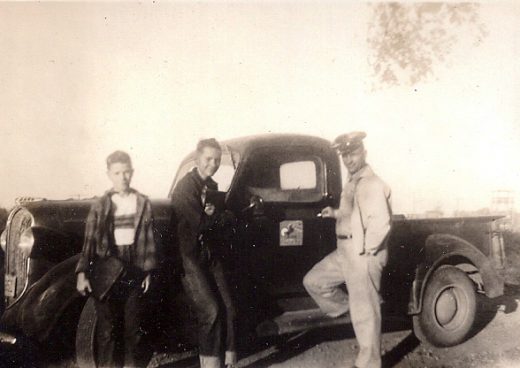

The exhibition features items from the Historic Costume and Textile Museum that were donated by Richard D. Rees, whose family owned a farm supply store, Rees’ Westside Farm Supply, in Coffeyville. The store supplied many home seamstresses with a selection of patterned feed sacks in the 1940s and 1950s. Rees’ mother made items for the family’s home from feed sack material as well as clothing for the family. Rees went on to earn bachelor’s and master’s degrees from Kansas State University. He later began collecting vintage feed and flour sacks from Kansas mills and bag manufacturers for the Historic Costume and Textile Museum. The collection currently includes 125 sacks and several homemade garments made with sack fabric.

Day said manufacturers offered bags, typically made of cotton, in different colors, patterns and themes to attract customers, who would reuse the bags to make a variety of clothing items or practical items such as curtains, placemats, pillow cases and hand towels.

“Although feed-sack dresses were often made out of need, in the hands of a seamstress with an eye for design, they didn’t have to look that way,” Day said. “With a bright and stylish print, double collar, decorative buttons and matching waist belt, a child’s dress from a feed sack wasn’t that much different from dresses one could buy in a department store at the time.”

Reusing feed sacks for clothing also was pitched as patriotic.

“During World War II, civilian women were encouraged to make do with what was available since cotton and wool were needed for military uniforms,” Day said. “Dresses lost ruffles, pleats, hoods and all but one pocket so that precious fabric could be used more efficiently. Shirtwaist dresses become a simple yet fashionable style for all ages. Fabric scraps would then be made into accessories such as belts to get the most out of the sacks.”

Underwear also got the sack treatment. Among the items in the exhibition is a pair of cotton bloomers worn by Nelda Jean Koons that were made by her older sister, Velma, from a 100-pound sack of chicken feed. Nelda was the youngest of six children in a family that farmed during the Great Depression in a Dust Bowl-stricken area of the Midwest.

“Wearing bloomers made from plain feed sacks was a common practice for children and adults,” Day said.

The sacks on display in “Thrift Style” also include prints of popular stars of the era, such as the Hillbilly Boys, a Texas-Western swing band in the ’30s, and Red Ryder, Little Beaver and Yaqui Joe from Dell’s Red Ryder Comics series. Some of the sacks are whimsical, such as the exhibition’s yellow feed sack with a “raining cats and dogs” print. The feed sacks could become toys, too, as demonstrated by a bag from the Eagle Milling Co. in Edmond, Oklahoma, that features a two-sided cut-and-sew girl doll wearing a green dress.

“During the depths of the Great Depression, the mill made a bold decision to add this bonus to its product,” Day said. “The dolls were printed on several sizes of feed sacks. The first doll wore a white dress with red stripes; in later printings the dress is blue, purple, red, yellow or green.”

Other bags by manufacturers featured in the exhibit were made to be embroidered later as tea towels or featured patterns suitable for placemats or pillow cases. Books, such as “A Bag of Tricks for Home Sewing” by the Cotton Council, were also available to inspire home sewers on ways to turn the bags into useful items.

Along with the feed sacks, Rees has donated a large number of business office garments and accessories worn by his late wife, Janet, in the ’50s and ’60s; a nearly complete collection of Trans World Airlines flight attendant uniforms; and several designer fashions. His donations were made in honor of his parents, Leonard and Beatrice Rees, and his wife. Rees also has established an endowment with the Kansas State University Foundation benefiting the Historic Costume and Textile Museum.

The Beach Museum of Art, at 14th Street and Anderson Avenue, is open Tuesday, Wednesday and Friday from 10 a.m. to 5 p.m.; Thursday from 10 a.m. to 8 p.m.; and Saturday from 11 a.m. to 4 p.m. Admission is free and free parking is available adjacent to the museum.