In this special book review series, authors will spotlight various resources addressing key ideas of community-engaged scholarship. The review essays offer perspectives on how stakeholders can co-create knowledge and build democratic communities.

In this special book review series, authors will spotlight various resources addressing key ideas of community-engaged scholarship. The review essays offer perspectives on how stakeholders can co-create knowledge and build democratic communities.

In this entry, Chibuzor Azubuike will review The Activist Academic: Engaged Scholarship for Resistance, Hope and Social Change by Colette Cann and Eric DeMeulenaere, 2020, Stylus Publishing.

Introduction

The Activist Academic was written by Colette Cann and Eric DeMeulenaere, two scholars and colleagues who met as cohort members during their doctorate program and now hold faculty positions in different universities. The book is intended to serve as a guide for scholars who are engaged in activism, and as a tool for academics who are interested in reimagining their research, work and teaching in ways that positively impact social change.

The book is written as a critical co-constructed autoethnography, though which the authors put forward their arguments in favor of academic activism. The text reflects their documented conversations over a 10-year period.

Summary of key ideas

The book is divided into seven chapters. In the first chapter, the authors discuss their journey into academia and define “activist academic.” Specifically, they identify the term activist before academic, implying that they are using the academia as platform for their activism. Cann explains:

Academia can be as you know, a powerful space to do racial justice and activist work, generally. Being here at Vassar, though has made me think more purposefully about what kind of academic identity will do righteous work, but also sustain me and my family emotionally, politically, socially, academically. (Cann and DeMeulenaere, 2020, p.7.)

They also discuss the politics of promotion for faculty members on a tenure track, since university systems do not often recognize activist achievements as academic milestones to be considered during a promotion.

In chapter two, they introduce a new methodological approach which was developed from critical theory, critical pedagogy, and critical race methodology which they call critical co-constructed autoethnography. They describe this method as similar to autoethnography, yet done collaboratively with a focus of campaigning against systems of oppression. The book itself utilizes this method through a form of dialogue that shows the flow of collaborative academic process and personal friendship as they critique the status quo together. They describe how this method helps them theorize along with the reader.

In chapter three, the authors provide a theoretical foundation for an activist scholarship geared towards social change. They posit that critical social theory supports the activist who is an educator. Critical social theory historically originated from critical pedagogy, critical race theory, and critical theory. In the academia, critical means questioning the norms as they are presented, rather than accepting them hook line and sinker.

Chapter four analyses scholars’ efforts in educational activist research. The authors present a framework for analyzing activist research with a focus on impact in line with dimensions of ideology, materiality, and scale. Put simply, studying topics that are not capable of transforming societies is not ideal, research must therefore have utilitarian value to society at large.

In chapter five, the authors illuminate the challenges of activist pedagogy in academia. They discuss different forms of pedagogy such as critical pedagogy, critical race pedagogy, and Queer pedagogy among others. They claim that these approaches are only theoretically aligned with activist pedagogy. They argue that an activist pedagogy is a refusal of schooling, of academia in discriminatory systems that limit imagination. They posit that an activist pedagogy is a pedagogy that is anti-oppressive in four dimensions in the classroom:

- Purpose: How is justice prioritized?

- Content: How is the content shaped by identities of those in the classroom and driven by issues of identity based justice?

- Identity: How is identity defined, considered, navigated in classroom spaces?

- Process: How do students and teachers interact in the interpersonal space in ways that do not mimic oppressive relationships in the society outside the classroom? (Cann & DeMeulenaere, 2020, p. 97)

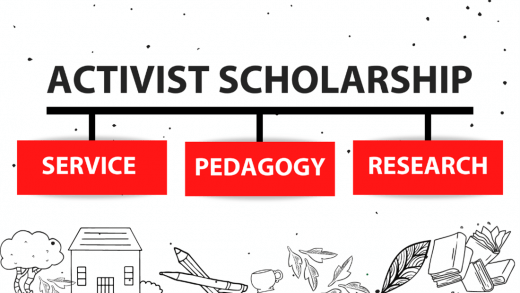

Finally, chapter seven explores at how core academic roles of service, research, and teaching (pedagogy) can complement each other (see Figure 1). The authors emphasize how these activities do not need to work in isolation, in fact they ought to complete each other. In my perspective, this means not just researching a phenomenon, but going a step further to facilitating implementation of research findings—that is, using a community-engaged model in teaching, service, and research.

Analysis

I found the method used by the authors of The Activist Academic to be quite interesting, because of the unique integration of ideas and my interest in these theories and approaches. They explain co-constructed autoethnography as a methodology steeped in critical theory, critical pedagogy, and critical race theory. In other words, critical co-constructed autoethnography creates spaces for collaborating researchers to work across differences, just like both of them came together to write this book. This is important because it is what engaged scholarship aims to achieve, rather than researchers working in isolation.

Just as the authors stated in the book that they entered into the academic as activists, Omotoso (2010) also argues that Nigerian women in the academia, whom she referred to as Acada Women, (Acada is the Nigerian colloquial word for Academy) ventured into this area to clamor for social justice and debunk androcentric foundations of the academia. She classified these women into second and third wave feminists and were visible in the public spaces where they advocated women’s rights.

From my perspective the term “activist” has been used closely to radicalism, therefore I am more comfortable with being referred to as a scholar-practitioner. Just like the activist-academic, the scholar-practitioner is also committed to social justice and transformation but without the baggage that comes with activism. Bruce and McKee (20202) describe transformative leadership as a continuum – from learner to ally to advocate to activist — which represents increasing public leadership roles and actions to support causes related to justice and equity.

Implications for community-engaged scholarship

One thing is clear, the aim of the book which is also evident in the methodology is to advocate for community-engaged scholarship.

Given that knowledge is co-produced, it is not possible for individual scholars to claim unique contributions. Rather, the research findings are developed in collaboration with community members.

This book illustrates how community-engaged scholars are activists. Community-engaged scholarship (CES) is an empowering process for the community where the members are part of the research and seek active partnerships with the community. Scholars who employ participatory methods are often classified as activists, and not all scholars want to be referred to as activists, for several reasons. It is against this backdrop that Scalet et al. (2020) created a relational model of public engagement as a framework for scholars that are interested in social change but do not want the baggage that comes with activism; for example the possibility of difficulty in earning promotion or getting into trouble with the university. Also, with the relational model the researcher is distant from the community and takes full credit of the work produced.

Furthermore, service activities conducted by scholars outside academia should be considered for promotion and tenure. A key question is, how can this be organized in a ways that do not cause chaos in the university? More research must be done to provide a framework for the practicality of this recommendation. Research from Imagining America offers insight for public scholars moving through the promotion and tenure process (Ellison and Eatmon, 2008). Their findings show that pursuing interests in public engagement is risky for faculty of colour. This submission is in line with the arguments in the Activist Academic, the university system was criticized by the authors as not being supportive of service component of faculty members.

References

Bruce, J., and McKee, K. (2020). Transformative leadership in action: Allyship, Advocacy, Activism. Emerald Publishing.

Cann, C., DeMeulenaere, E. J. (2020). The activist academic: Engaged scholarship for resistance, hope and social change. Myers Education Press.

Ellison, J., and Eatman, T. K. (2008). Scholarship in public: Knowledge creation and tenure posicity in the engaged university [White Paper]. Imagining America. https://iagathering.org/mainsite/wp-content/uploads/TTI_FINAL.pdf

Omotoso S.A. (2020). Acada-activism and feminist political communication in Nigeria. In Omotoso S. (Ed.) Women’s Political Communication in Africa (pp. 155-172). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-42827-3_10

Schalet, A. T., Tropp, L. R., and Troy, L. M. (2020). Making research usable beyond academic circles: A relational model of public engagement. Analyses of Social Issues and Public Policy, 20(1), 336-356.

About the author

Chibuzor Azubuike has ten years of experience in community service. She is the founder/director of Haske Water Aid and Empowerment Foundation, a non-profit organization which focuses on providing potable water for vulnerable people and youth empowerment. Chibuzor is interested in building civic leaders that would solve complex societal problems, especially in developing countries. The doctoral program in leadership communication will help her to build transferable leadership skills, and contribute to scholarship on leadership, social change and development.

Chibuzor Azubuike has ten years of experience in community service. She is the founder/director of Haske Water Aid and Empowerment Foundation, a non-profit organization which focuses on providing potable water for vulnerable people and youth empowerment. Chibuzor is interested in building civic leaders that would solve complex societal problems, especially in developing countries. The doctoral program in leadership communication will help her to build transferable leadership skills, and contribute to scholarship on leadership, social change and development.