Continuing the Leadership in Democracy blog series, Don Dunoon, author and leadership development specialist, discusses collective and individual dimensions of leadership learning, development and practice.

In an earlier post, Brandon Kliewer proposed three categories of leadership learning and development for advancing the project of democracy. One aspect that I’d like to tease out is that the practice of leadership, whether in furthering democracy or seeking to make progress in any other area of change, has both collective and individual dimensions.

My aim is that readers will consider what follows as propositions to spark reflection and conversation, rather than solidly evidenced conclusions. Considering leadership learning and development, and practice, through both collective and individual lenses requires a degree of “standing back” from conventional assumptions about leadership.

After decades of preoccupation in the leadership literatures with “the leader” and such aspects as leader-follower interactions and leader capabilities and qualities, the past decade or more has seen increasing attention to leadership as a collective phenomenon. Some of the writings from this perspective, however, do not seem to acknowledge an individual component of leadership. This might reflect concerns about “re-platforming”, re-energizing conventional notions, such as to do with leaders and followers.

Yet, allowing a place for the exercise of leadership by individuals need not imply falling back into regarding leadership as synonymous with either leaders – whether by virtue of their authority or exceptional (or other) attributes – or “leading”, in the sense of “going first” or taking charge of a situation.

Leadership as practiced by an individual takes place largely through conversation, as well as experimentation. Leadership is an in-the-moment activity, occurring at those times when we give priority to the quality of communication and interaction over and above task achievement (which is also vital, but in other moments).

Exercising leadership as a practice involves efforts to help build shared meaning, at least as far as possible, accepting residual and perhaps unbridgeable differences of perspective are likely. Ideally, the aim is to build common understandings both about preferred futures, including purpose and vision, and the current situation. As a group moves towards clarity, there is the prospect of drawing forth energy and further action in support of deep-reaching change.

For a group to make progress, ideally there are contributions by more than one member, in keeping with the idea of leadership as collective as well as individual. A key, though, with the individual component is that exercising leadership is not just about “jumping into” a conversation. Instead, this is intentional, deliberate work.

We can characterize such interventions as “relational.” Intervening relationally implies engaging with others so as to: recognize that the issues we are dealing with are complex, multifaceted, with our own being potentially one of many perspectives; working from observational data and consciously making and testing interpretations; seeing difference with others as an opportunity for learning, while respecting their humanity and unique experience and story; and consciously seeking to surface and explore underlying assumptions and mindsets, including our own. Relational conversation here is taken as synonymous with dialogic conversation. Leadership as a practice necessarily involves efforts towards dialogue.

Dialogue, while necessary, is problematic. Relationally oriented communications as described above are often avoided or sidestepped. There are multiple factors at play here. One is that groups and individuals with an interest in a civic issue often have particular objectives to achieve. Their view is “right” and others can be seen as misguided or self-interested. As well, there can be pressures on civic officials and others to achieve results quickly and avoid upsetting others. This last factor, keeping things calm and smooth, is possibly the biggest difficulty for those seeking to enact leadership and dialogue. Put simply, dialogue – as it involves surfacing and exploring differences of viewpoint – is prone to give rise to threat and unease, potentially anxiety.

Desires to minimize/avoid threat and stay in control are likely to lead many who could otherwise contribute to civic leadership through dialogue instead to seek to “manage” a situation. What I term “management mode” action here refers to focusing on the more concrete, tangible aspects of the issue (as distinct from the hidden, implicit and potentially more threatening aspects); on task accomplishment, getting things done; and using whatever relevant authority we bring to the situation to achieve our objectives. Management, like leadership, is collective as well as individual.

Consider the example of a municipal council undertaking community consultation to gain input on a plan for re-use of a former industrial site. The emphasis is on tangibles, such as the plan and input; task action, as with inviting community consultation; and using the Council’s authority as the body with jurisdiction over the land. Potentially, the council manager in charge of the project might prefer to exercise leadership and adopt a more dialogic approach in engaging with the community, but falls into line, seeks to minimize risk and psychological threat, and thus goes down the management-mode path.

If, however, that manager has a keenly developed individual practice of leadership – as well as management – the individual may be able to weigh up the risks and potentially “lean into” a more leadership-oriented intervention. This will be more likely to the extent that this individual and others are able to critically appraise different meanings of the common good in this instance, avoid dignitary harm, and be able to sort through the dynamics and patterns in their interactions. Yet, an individual being able to consciously choose to enact leadership in this situation, rather than defaulting to management, may have a significant impact in advancing a more dialogic and pro-democracy exploration of the specific challenge in that community.

Perhaps the time has come for more scholarly attention to potential synergies arising from considering leadership learning, development and practice as having both collective and individual dimensions.

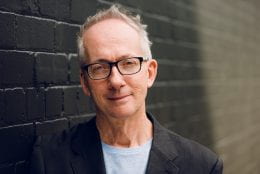

More about Don Dunoon

Don Dunoon is a Sydney-based leadership development specialist and author. His book, In the Leadership Mode, frames leadership as a form of in-the-moment intervention in dealing with contentious issues and different from management as another form of intervention. Dunoon is the author of articles in international journals including one with acclaimed Harvard mindfulness researcher, Ellen Langer. He is the developer of the OBREAU conversation model (Observation, Reasonableness, Authenticity) and is partner with HealthCareCAN (Canada’s peak hospitals and health services organization) in an e-learning course, “Talking about Tough Issues.” With 25 years’ leadership development experience, his passion is in helping organizations, groups and individuals achieve practical results through applying conceptually grounded tools. He has presented at several international conferences including – with K-State colleagues Trish Gott and Mary Tolar – at the 2020 (virtual) conference of the International Leadership Association.

Insightful article that speaks to the complex and emergent nature of Leadership and Management. Don asks us to go beyond those dichotomies that limit us from seeing the reality that is both grey and fuzzy. A person well versed in the practice of Leadership embraces a broader and meta understanding of the context and landscape, having this understanding enables them as Don states to be able to weigh up the risks and potentially “lean into” a more leadership-oriented intervention.