–by Raymond Cloyd

This is the time of year when the Asian ladybird beetle, Harmonia axyridis adults start entering homes and becoming a nuisance. The Asian lady beetle is a native of Asia and was introduced into the southeastern and southwestern portions of USA to deal with aphids on pecan trees. However, the Asian ladybird beetle has spread rapidly to other portions of the USA. The Asian ladybird beetle is a tree-dwelling ladybird beetle, more so than the native species of ladybird beetles, and is a very efficient predator of aphids and scales.

During fall and early winter, when the weather is cooler, Asian ladybird beetle adults start aggregating on the south side of buildings and entering homes. The beetle does this because in their homeland of China they inhabit tall cliffs to overwinter. There are very few “tall cliffs” in Kansas—so the next best thing is a building.

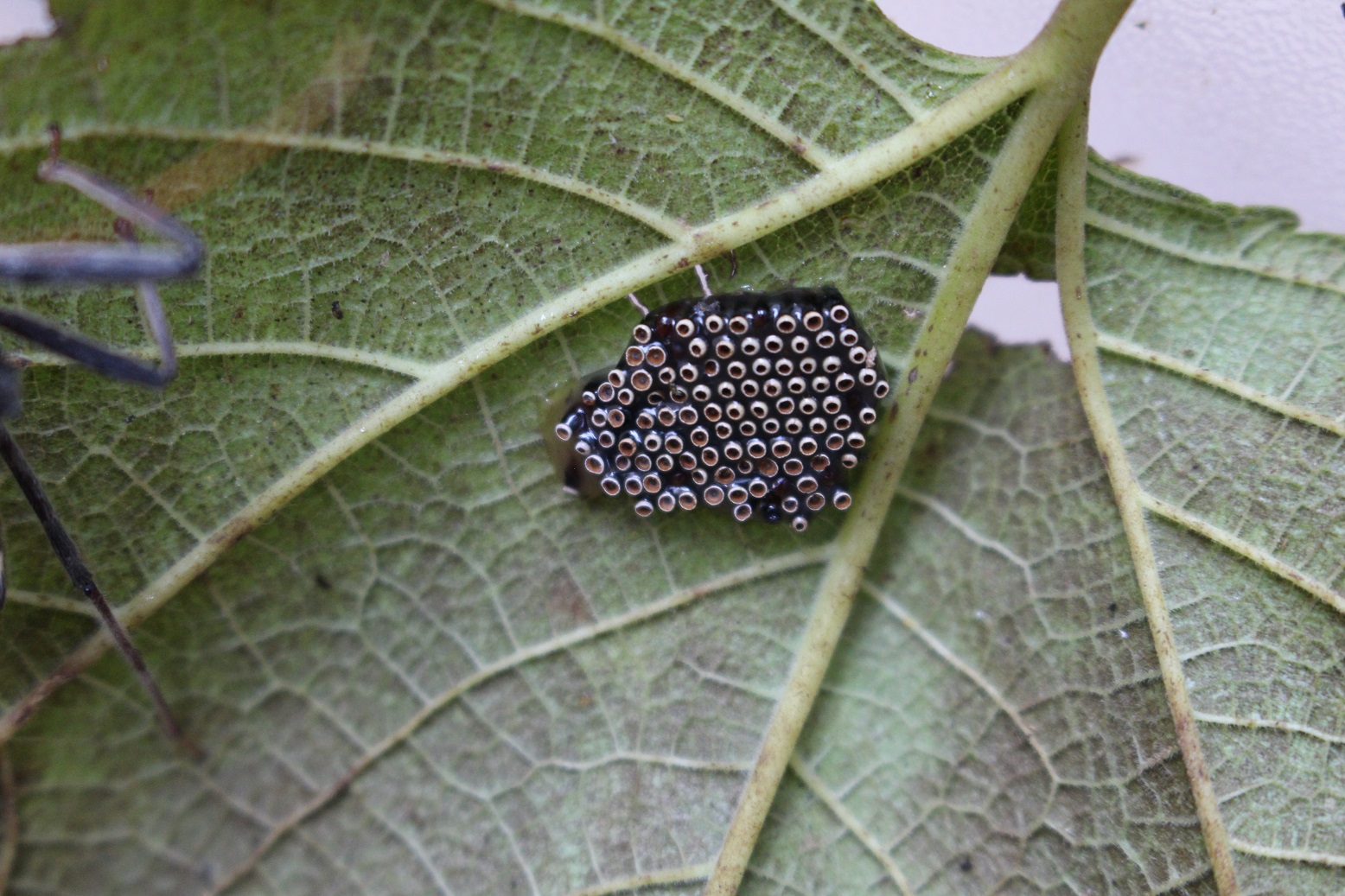

The Asian ladybird beetle can be easily distinguished from other species of ladybird beetles by the presence of a pair of white, oval markings directly behind the head, which forms a black M-shaped pattern. Adults are 1/4 inch long, 3/16 inch wide and yellow to dark-orange colored. In addition, their body is usually covered with 19 black spots. Adults can live up to 3 years. Female beetles lay yellow, oval-shaped eggs in clusters on the underside of leaves. The eggs hatch into larvae that are red-orange and black in color, and shaped like a miniature alligator. The larvae are primarily found on plants feeding on soft-bodied insects such as aphids and scales. They eventually enter a pupal stage. Pupae can be seen attached to plant leaves. The adults emerge from the pupae and start feeding on aphids. Adults can be found on a wide-variety of trees including apple, maple, oak, pine, and poplar.

Asian ladybird beetle adults are a nuisance pest because they tend to aggregate and overwinter inside buildings in large numbers. The beetles release a pheromone that attracts more beetles to the same area. Although the beetles may bite, they do not physically harm humans nor can they breed or reproduce indoors. Beetles are attracted to lights and light-colored buildings, especially the south side due to the warmth provided when they bask in the sunlight. The beetles then work their way into buildings through cracks and crevices. Dark-colored buildings generally have fewer problems with beetles (so now is the time to paint your house). Adult beetles will feed on ripening fruit such as peaches, apples, and grapes creating shallow holes in the fruit. Large numbers of beetles feeding on fruit may cause substantial damage so that the fruit is less appealing for consumption.

Beetles may be prevented from entering homes by caulking or sealing cracks and crevices. Beetles already in homes can be physically removed by sweeping them or vacuuming. Be sure to thoroughly empty the vacuum bags afterward. Do not kill the beetles. Just release them outdoors underneath a shrub or tree away from the house. Commercially available indoor light traps can be used to deal with beetles indoors. The traps need to be placed near the center of a room and they are only effective at night in the absence of competing light. In addition, they work best when room temperatures are 75°F or higher.

If crushed, the beetles will emit a foul odor and leave a stain. The dust produced from an accumulation of dead Asian ladybird beetle adults behind wall voids may incite allergies or asthma in people. Although there are some sprays available, the use of insecticides is not recommended for indoors.

Homeowners that want to avoid dealing with overwintering beetles entering their homes can hire a pest management professional to treat the points of entry on the building exterior with a pyrethroid insecticide. The treatments need to be made in late September or early October before the beetles enter the building to overwinter. Beetles that are feeding on fruit can be “controlled” with insecticides commonly labeled for use on fruit trees.