——-by Brian McCornack, Wendy Johnson, Jeff Whitworth, J.P. Michaud, Sarah Zukoff

Kansas State University is leading a Sugarcane Aphid Monitoring Network comprised of researchers across the Southern half of the US. This group effort results in a national reporting and mapping of aphid distribution in real-time during the growing season using the online Extension program, myFields.info.

In general, migrating populations of sugarcane aphid disperse north from Southern Texas and northern Mexico into Oklahoma and then Kansas depending on weather patterns, temperature, and potential factors limiting aphid population growth, including natural enemies and use of resistant sorghum hybrids. No overwintering in Oklahoma and Kansas has been reported due to a lack of host plants (i.e. grain sorghum and green Johnsongrass) during winter months. Real-time tracking of migrating populations of sugarcane aphid into Kansas results in early detection of this pest for local farmers, which is necessary for timely applications of insecticide, a primary practice for protecting sorghum crops. See our Scouting Card (see picture below) for more management information.

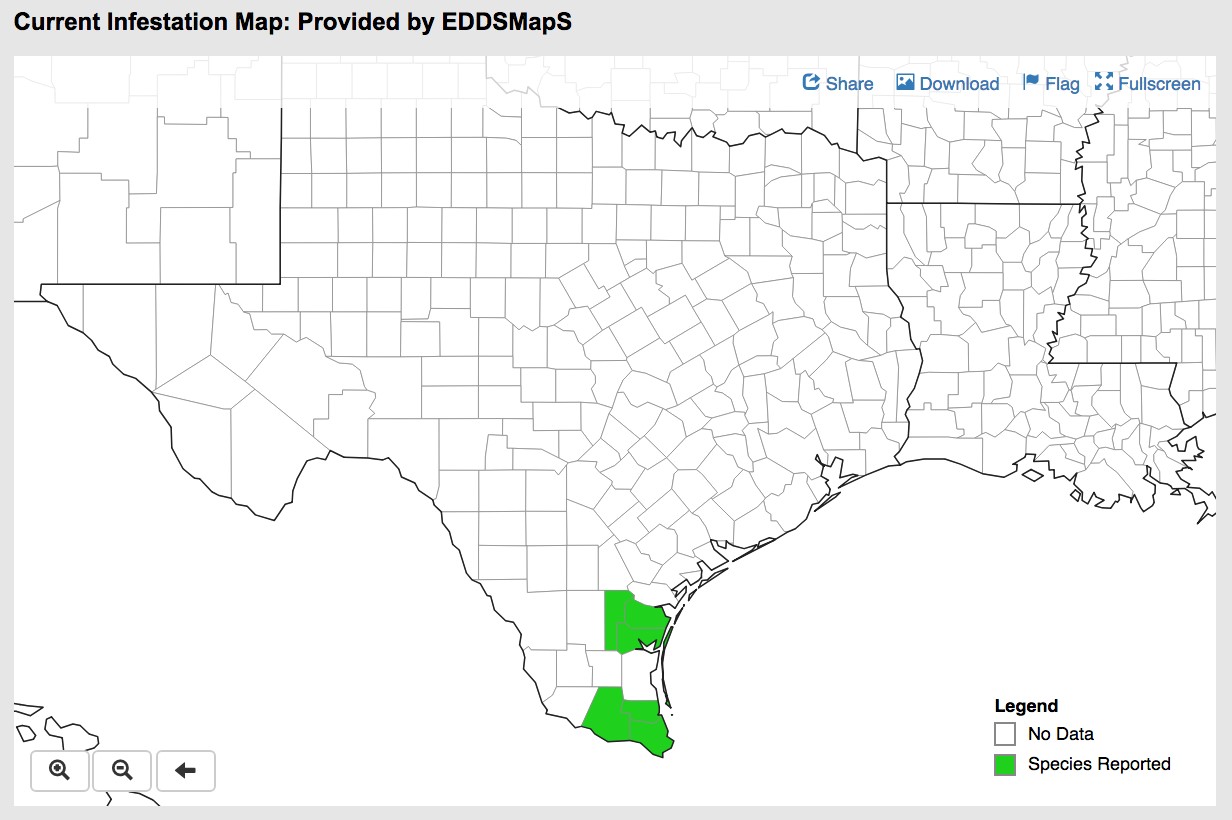

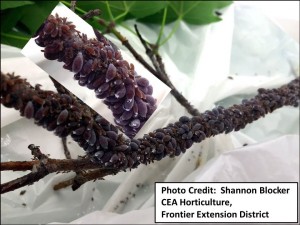

The first observation of sugarcane aphid occurring in production sorghum this season was in southern Texas on March 28, which is not unusual. Colleagues in Texas have indicated that overall aphid presence and population levels at this time are sparse in comparison to previous years. By April 19, SCA was detected only several counties (see picture below) north of the initial report, suggesting that northern movement could progress much slower than past seasons, even in regions where these aphids are known to overwinter on Johnsongrass. As we wait to see how northern migration of SCA plays out, you can plan your management strategy by reviewing current recommendations using the following link to myFields.info: https://www.myfields.info/pests/sugarcane-aphid. In addition, create a free account on myFields.info and be automatically signed up for state- and county-level email alerts when SCA is detected in your area. Furthermore, localized alerts will include contact information for Extension support in your area.

Future monitoring group efforts will include the release of a threshold-based sampling plan for help in making management decisions for SCA, improved mapping features for displaying the change in aphid distribution over time, and mapping the predicted movement of SCA before it happens to help inform farmers.