–by Eva Zurek

Insect Diagnostic Laboratory Report

http://entomology.k-state.edu/extension/diagnostician/recent-samples.html

–by Eva Zurek

Insect Diagnostic Laboratory Report

http://entomology.k-state.edu/extension/diagnostician/recent-samples.html

–by Dr. Bob Bauernfeind

Whereas scratching an itch sometimes provides satisfying (almost pleasurable) relief, at other times scratching an itch can be painful and distressing. The latter situation is attributable to the mite, Pyemotes herfsi (Oudeman).

Unlike chiggers which have been long-recognized for producing annoying but fleeting bouts of itchiness, mysterious “bites” causing raised quarter-sized reddened areas each with a centralized pinhead-size blister were of widespread occurrence in 2004 in various Midwestern states.

Through investigative studies, the aforementioned Pyemotes herfsi mites were identified as being responsible for the mysterious bites. Although the existence of these mites had been well known for multiple decades, the correlation between them and reported widespread occurrences of human discomfort was unknown. The severity of the 2004 outbreaks resulted in cooperative efforts between K-State and the University of Nebraska entomologists, the resultant being the identification of Pyemotes herfsi as responsible for the stressful skin disorders.

Pyemotes herfsi were recovered from marginal fold galls on (primarily) pin oak leaves. Marginal galls are associated with the larvae/maggots of tiny midges. That is, Pyemotes herfsi prey upon the midge larvae. The following side-by-side close-up images show an intact marginal gall, and a dissected gall revealing female Pyemotes herfsi. Despite their small size, they become readily visible due to their bulbous abdomens which can contain up to 200 offspring.

Due to their minuscule size compared to that of midge larvae, Pyemotes herfsi possess a potent neurotoxin used to paralyze their maggot hosts. This toxin is that which is responsible for initiating the skin irritations which cause discomfort in individuals upon which Pyemotes herfsi happen to come in contact with. Because Pyemotes herfsi are associated with the midge larvae responsible for marginal galls on oak leaves, Pyemotes herfsi have been given the common name, Oak Leaf Itch Mite. It is believed that oak leaf itch mites also prey upon the larvae of another closely related midge species responsible for the formation of vein pocket galls on the undersides of oak leaves. A full description of the oak leaf itch mite life cycle is available online by accessing Kansas State University Extension Publication MF2806.

The good news is that oak leaf itch mite populations may be extremely low or absent for years-on-end —— people can enjoy the outdoors without having to contend with oak leaf itch mite encounters. The bad news is that the reappearance/resurgence of oak leaf itch mite populations is unpredictable. There are various unknown factors as to the whys-and-where their populations are and when they will surge. Undoubtedly there are ever-present reservoir populations of oak leaf itch mites, but, where are they? Possibly a major factor for population explosions is contingent on fluctuating populations of the appropriate gall midges responsible for the formation of marginal galls and/or vein pocket galls. An intriguing question then would be, “How do the tiny mites detect and move to the galls up in tree canopies?”

More bad news: Each female oak leaf itch mite produces many progeny. And the developmental cycle is reported to be just 7 days. The resultant is the production of uncountable numbers of oak leaf itch mites which ultimately leave the confines of leaf galls. Passive dispersal via air currents is the bane to people, especially those in neighborhoods where pin oaks constitute the main trees species.

The bad news continues: There is a wide time frame during which encounters with oak leaf itch mite might occur. It is not only the initial late summer encounters, but the presence of oak leaf itch mites extending well into the fall when people are raking leaves and kids having fun playing in leaf piles.

And if this is not enough negativity regarding oak leaf itch mites, there is little to be done (well, actually nothing to be done) in treating and reducing/eliminating their populations. THEY WILL HAVE THEIR WAY!

The people who are most likely to encounter oak leaf itch mites will be those in living in areas/neighborhoods where oaks (again, especially pin oaks) are the dominant tree species. When oak leaf itch mite populations are excessive, restricting outdoor activities is one method of reducing the risk of exposure. While the use of repellents may work against annoying insect species which actively seek a host, repellents have little effect against oak leaf itch mites which are passively dispersed, and lack the ability to alter their course/direction. It has been suggested that susceptible individuals (yes, some people do not have negative reactions to oak leaf itch mite bites) spend as little outdoor time as possible. And showers immediately upon returning indoors might eliminate/wash off mites before they bite and cause reactions.

Individuals experiencing oak leaf itch mite encounters might utilize medications and lotions so designed to provide relief from itching discomfort as well as secondary infections of excoriated areas. Seek advice and recommendations from appropriate personnel.

–by Dr. Bob Bauernfeind

Pushing the envelope (as I often do), how does one use Muhammad Ali’s “Float like a butterfly, sting like a bee”, epitomized boxing style, and the movie Poltergeist tagline, “They’re here”, as an introduction to a Kansas Insect Newsletter article? I spent time on Saturday and Sunday doing yardwork. It was Sunday afternoon that (out of the corner of my eye) I frequently glimpsed monarch butterflies lazily/lightly floating by. I had noticed none the day before. So, “They’re here” refers to their arrival in Kansas (well, Manhattan) on Sunday as they were on their southward migration to their overwintering grounds in Mexico.

There are individuals with passionate interests in the status of monarch butterfly populations and activities. Avid monarch-watchers access websites which better document the current presence/movements of migrating monarchs. My sighting certainly has no official status in terms of documentation —- just a “casual” observation on my part.

–by Dr. Jeff Whitworth and Dr. Holly Schwarting

The majority of the double cropped sorghum seems to be past flowering and almost to the soft dough stage. This means much of this crop is almost past the susceptible stage relative to corn earworms (a.k.a. sorghum headworms), which is about soft dough. Later planted sorghum still needs to be monitored though as earworm moths are still ovipositing in sorghum heads. Sugarcane aphids (SCA) are still very active in north central Kansas, as are their natural enemies, and thus these populations should also continue to be monitored. The insecticides registered for sugarcane aphids have performed really well at controlling these aphids, as have the products used for controlling headworms. Just remember, gallonage is extremely important for SCA applications.

–by Dr. Jeff Whitworth and Dr. Holly Schwarting

Double cropped soybeans are still very much in the reproductive stages throughout north central Kansas. Thus, they are still vulnerable to a variety of pests – and pest populations seem to be increasing. Green cloverworms (see pic) have been feeding on leaves for the past couple of weeks but are starting to cease feeding to begin pupating. They rarely cause actual yield loss but usually cause concern because of the amount of defoliation they often cause. While green cloverworms don’t feed on the pods or seeds, adult bean leaf beetles and corn earworm larvae (a.k.a. soybean podworms) do (see pics). Both species, bean leaf beetles and corn earworms, seem to be increasing throughout south central and north central parts of the state. The corn earworm larvae will usually feed on the seed within the pod and will only feed for about 10-14 days. However, bean leaf beetles will continue to feed until harvest, or they disperse to overwintering sites.

There are still a few soybean aphid populations in north central Kansas, however there are more winged adults present which probably means they are mostly finished feeding and preparing to migrate to overwintering sites (they probably do not overwinter successfully in Kansas – we hope).

We have received several calls this week relative to these “interesting little green worms” in soybeans. These are silver spotted skipper larvae and will feed on leaves but should not defoliate enough, on a field-wide basis, to impact yield.

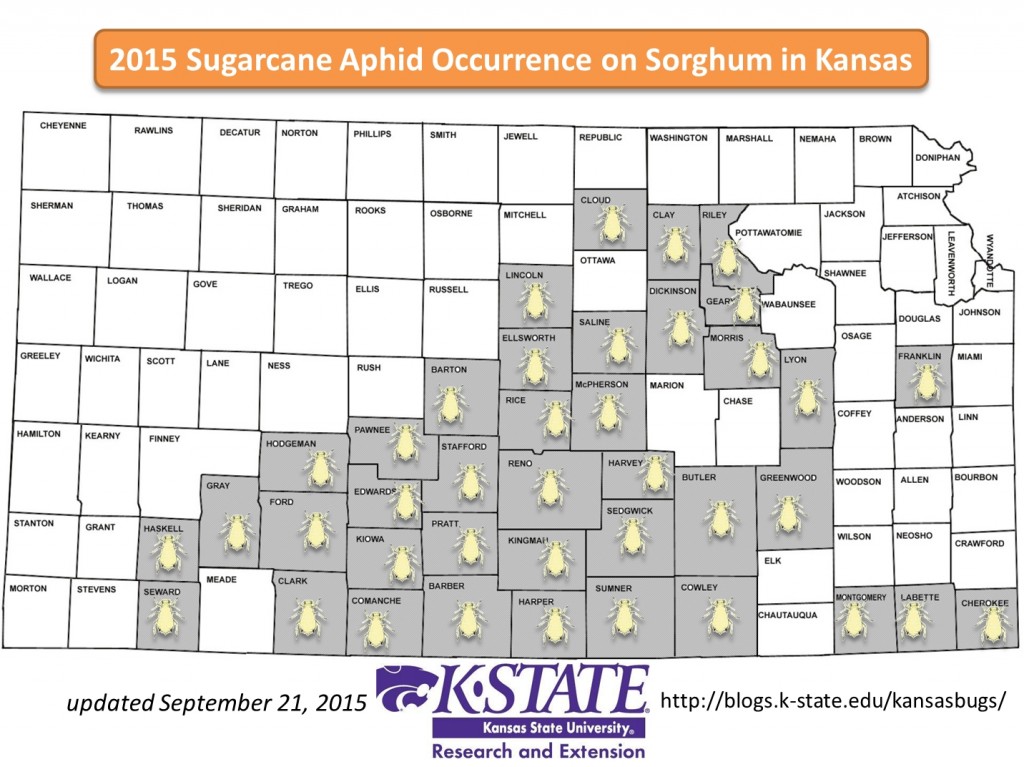

The sugarcane aphid (SCA) movement in Kansas has slowed down for the moment with the sorghum crop maturing and drying down. South-central Kansas seemed to be the “hot zone” this year, but many counties further north and west got to see populations of these aphids as well. Some chemical rep’s have suggested spraying sorghum fields as soon as SCA populations of any size are found, however finding a few SCA does not necessarily warrant immediate treatment. Using our new thresholds (found here), many farmers outside of the “hot zone” in Kansas did not have to spray their sorghum fields for SCA.

Next season it will be important to monitor the progression of the SCA northward from TX and OK and observe thresholds before treating. This is especially important because populations of SCA can be swept into the same fields multiple times depending on the weather, and the chemical options for treating the SCA will be even more limited next year. A federal judge recently ruled against the sale of Sulfoxaflor which is the active ingredient in one of our best tools against SCA, Transform insecticide (Article here). Our SCA Task Force is currently working on what this means for SCA control next season, but it will likely mean that Transform will not be sold anymore. We will keep you posted on this issue.

This map shows the states where sugarcane aphids were found in sorghum as of Sept. 18th this year. So far, several new state records have been recorded including Virginia, Tennessee, New Mexico, Colorado, and Illinois.

–by Eva Zurek

Insect Diagnostic Laboratory Report

http://entomology.k-state.edu/extension/diagnostician/recent-samples.html

–by Dr Bob Bauernfeind

A second spark was in the form of an e-mail received from Dr. Sarah Zukoff at the Southwest Research and Extension Center in Garden City: carpenterworms.

Over many years of operating blacklight traps throughout Kansas, I have collected hundreds of carpenterworm moths. Female moths are large (wingspread up to 3 ¼ inches) and rather drab in appearance. Male moths are smaller (wingspread ½ that of the female) and also appear drab when wings are folded. But upon spreading the forewings and exposing the hindwings, the coloration and pattern of the male’s hindwings is strikingly different from that of the female.

As common as the moths are, I have only been “on-site” once. On 10/04/2010, I arrived in McPherson in response to a resident’s request. It was apparent that carpenterworms were at work. They were creating tunnels and expelling large amounts of sawdust (a combination of wood chewings and frass) which was accumulating at the base of a large green ash situated next to a house. Given that carpenterworm life cycles are lengthy (2-3 years depending on environmental factors), the currently-present carpenterworms originated from eggs deposited in 2007 or 2008.

This tree has been under attack over a period of years as seen by extensive scarring of the bark. While the scarred bark surface presented a “healed appearance”,

it concealed the extreme underlying damage accrued by previous carpenterworm activities.

While carpenterworms seldom kill tree hosts, their extensive feeding damage reportedly can structurally weaken trees resulting in the breakage/falling of limbs and entire trees. This was the concern of the homeowner given the proximity of the tree to her house. Granted that while I am not a bona fide “tree person”, my unqualified assessment was that the tree was structurally sound. The local arborist disagreed and recommended removal. I was not present at the time of removal (December), but I did travel back shortly thereafter. The size of the borer tunnels were impressive in a cross section from the trunk. Yet, it was interesting to note that despite the ominous presence of carpenterworm activities, their tunneling activities were dismissive in comparison to the amount of solid wood. The tree was structurally sound.

A little background regarding carpenterworms. Although most people probably are not familiar with carpenterworms, they are not a “new pest species”. We are approaching the second century anniversary of the year in which they were first reported to damage trees (1818). Carpenterworms attack a wide variety of tree species including ash, birch, black locust, cottonwood elm, maple, oak and willow. Fruit trees such as apricot and pear are also listed, and possibly (by extension) would also include most any fruit tree species.

The carpenter worm developmental life cycle varies depending on their geographical latitude: 1-2 years in the Deep South to 4 years in the Northern States and southeast Canada. In Kansas (being somewhat in the middle), the carpenterworm life cycle probably lies between 2-3 years. However in any given year, overlapping generations are likely to occur.

Given a 3-year scenario: Female carpenterworm moths reportedly produce between 200 and 1,000 eggs which are preferably deposited in protected/hidden sites (bark crevices, under lichens, and near wounds and scars) on tree trunks and main/larger limbs. Newly hatched larvae penetrate the bark, or enter through existing openings. They create shallow tunnels in the inner bark in which they overwinter. Feeding resumes in the spring at which time larvae extend and widen tunnels. Moving inward, they form upward-slanting tunnels into and through the sapwood and then into the heartwood where they form vertical tunnels in which they overwinter. In the third summer, the vertical tunnels are extended (up to 9 inches long) and expanded (over ½-inch diameters). In the fall, larvae return to the area of the exit hole in the bark and produce a silken layer which lines the gallery walls and forms a curtain over the exit hole. Larvae then overwinter a final time. In spring, larvae move close to the exit hole and are transformed into pupae. Just prior to moth emergence, pupae will wiggle and force their way through the silken curtain. With the anterior of pupae thusly exposed, moths emerge outside of the tree where they will harden and be “free” to take flight.

Carpenterworms have a negative impact on lumber production. Individual or cumulative damage associated with extensive tunneling, staining and wood decay may seriously degrade the quality and quantity of lumber from individual trees. Fortunately, however, carpenterworm distribution (and consequently damage) within fully forested lumber production areas appears to be less than that seen on open-grown shade trees, roadside trees or trees in shelterbelts and edge-of-the-woods trees.

Due to the unpredictable appearance/occurrence of carpenter worms, little can be done in a preventative sense. The presence of carpenterworms usually is detected late (the third year) in their developmental cycle when excessive sawdust accumulations catch one’s attention. While the damage has already occurred, some people will attempt to kill larvae by inserting a wire probe into the carpenterworm’s tunnel. Depending on the larva’s position in the tunnel system, this may or may not work. If a person attempts to force a stream of insecticide into the tunnel, care should be taken to avoid a backsplash of the insecticide stream. Because carpenterworms seem to prefer repeatedly attack the same tree and ignore nearby trees, the “magnet tree” can be removed, thus eliminating the major local source of carpenterworm moths.

–by Dr Bob Bauernfeind

There are times when I struggle coming up with a “timely topic” for the Kansas Insect Newsletter. But then I encounter something that “ignites the fire”.

The spark? – Yesterday morning (Labor Day), I went out to water my tomatoes. I noticed a portion of a branch lying on the ground. Picking it up, the end/break point had the characteristic smooth buzz saw cut pattern of a twig girdler.

The following is a cut-and-paste from a previous Kansas Insect Newsletter. So possibly (for some) this will be “old news”, but a useful review. For first time readers, this hopefully will be interesting and informative “new news” regarding the seasonal activities of Oncideres cingulata, the longhorned beetle commonly called the twig girdler.

Given its name, the image below shows a “fresh girdle”.

One has but to look at the head of a twig girdler to realize that it is well-equipped for the girdling task. The head is compressed from front to back, and somewhat elongate from top to bottom —- just right for allowing it to fit into the V-shaped girdle it creates. Under magnification, her mandibles resemble the “jaws-of-life” rescue equipment —- stout and strong, ready to cut/girdle branches ranging in size from 6 to 13 mm in diameter —- apparently dependent on the size of the individual female beetle whose legs are uniquely positioned —– her 4 front legs to encircle/grasp, and her hind legs positioned rearward and utilized to anchor against.

The girdling process is not a complete shearing of branches. Rather, the smooth cut stops, but an intact central core remains, thus preventing the branch from dropping. However, because girdling severs vascular elements, the portion of the branch beyond the girdle dies and dries out. This results in the central core becoming brittle. It is at this point, then, the weight of the branch (with or without the aid of the wind) overcomes the ability of the core to support the branch. The core snaps and the branch falls to the ground.

Twig girdlers have a wide host range including hickory, pecan, dogwood, honeylocust, oak, maple and hackberry. While hackberry is listed as “high” on the list of hosts, in Kansas, most reports of littered lawns occur beneath elms. This preference for elm over hackberry was exemplified in an observation of side-by-side girdled elms and untouched hackberry trees.

Several questions arise regarding girdlers:

Why do they girdle branches? The larvae of twig girdlers require a “drier wood” for their growth and development. Beetles deposit their eggs beyond the “cut” thus ensuring the survival of the larvae in the fallen branches. Beetles gnaw through the bark (creating an ovipositional scar) and deposit an egg just beneath the bark. Egg sites can easily be detected by closely examining areas near twig side shoots.

Of what harm are girdlers? This depends on where and what they are girdling. In nut production orchards, twig girdlers can be detrimental when damaging newly transplanted trees or stymieing/setting back young trees not yet in production mode. In harvestable orchards, there have been reported incidences of reduced nut production and reduced yields following extensive twig girdler activities the previous season.

Can people monitor for the presence of twig girdlers and apply an insecticide treatment to eliminate them before their girdling activities? This is impractical. There is not a single succinct time of beetle appearance. Rather, their emergence pattern is lengthy, spanning from late August into October. This being said, the impracticality continues. It is not possible to inspect large trees for the presence of beetles. And while twig girdlers have a very distinctive appearance, they can be easily overlooked because they blend in to the background.

For homeowners, twig girdlers are more of a nuisance in causing the aforementioned branch litter. The recommendation is to gather up and dispose of branches. This will eliminate those beetles which emerge the following year. However, this does not mean that twig girdlers won’t appear the following year: look up, and you may see many more dead branches still attached or caught up in tree canopies.

For certain, there is one site where girdling activities have ceased.

–by Dr. Raymond Cloyd

If you haven’t noticed yet, hordes of goldenrod soldier beetle (Chauliognathus pennsylvanicus) adults are feeding on goldenrod (Solidago spp.) and other flowering plants such milkweed (Asclepias spp.). Adults are extremely abundant feeding on the flowers of chive (Allium Schoenoprasum), and can also be seen feeding on linden trees (Tilia spp.) when in bloom. In fact, adults may be observed both feeding and mating (occasionally at the same time). The goldenrod soldier beetle is common to both the western and eastern portions of Kansas.

Adults are about 1/2 inch (12 mm) in length, elongated, and orange in color with two dark bands on the base of the forewings (elytra) and thorax (middle section). They are typically present from August through September. Adult soldier beetles feed on the pollen and nectar of flowers, but they are also predators and may consume small insects such as aphids and caterpillars. Flowers are a great place for the male and female soldier beetles adults to meet, get acquainted, and mate (there is no wasting time here). Soldier beetle adults do not cause any plant damage. Sometimes adults may enter homes; however, they are rarely concern. The best way to deal with adults in the home is to sweep, hand-pick, or vacuum.

Adult females lay clusters of eggs in the soil. Larvae are dark-colored, slender, and covered with small dense hairs or bristles, which gives the larvae a velvety appearance. Larvae reside in the soil where the feed on grasshopper eggs; however, they may emerge from the soil to feed on soft-bodied insects and small caterpillars.