(Megan Kennelly, KSU Plant Pathology)

I haven’t received any Pythium foliar blight samples yet, but I wanted to provide a heads up and reminder.

Pythium foliar blight, sometimes called cottony blight, is one of the most destructive turfgrass diseases. The disease can explode in only a few days if conditions are right. Perennial ryegrass and tee- or fairway-height creeping bentgrass are the most common hosts in Kansas. Though Pythium root rot (caused by different species) is common in putting greens, Pythium foliar blight is rare in putting greens. In 10 years, I have seen it only ONE time on a putting green. Tall fescue, Kentucky bluegrass, bermudagrass, and zoysiagrass can become infected, but this is extremely rare.

Conditions for Disease Development

The risk of Pythium blight is highest during humid weather when day temperatures are 86 to 95 degrees Fahrenheit and overnight lows are consistently at least 68 degrees Fahrenheit.

The disease is most common when soils are saturated with water, due to excessive rainfall or irrigation. Long dew periods, high relative humidity, and lush, dense turfgrass growth also favors disease development. Low areas, sites with poor air flow, and sites with poor drainage are particularly vulnerable.

Symptoms

In fairway-height bentgrass and perennial ryegrass, the first symptoms are irregularly shaped, water-soaked, greasy patches up to 4 inches in diameter.

If it is humid, a cottony growth may be present early in the morning.

The patches may merge into larger blighted areas.

The pathogen can be spread by equipment and in water drainage patterns. Here is some Pythium blight at Rocky Ford a couple of years ago, following the pattern where heavy rain caused a water flow across this plot from left to right.

Look-alikes: Pythium blight can be confused with brown patch, damage due to thick thatch, drought stress, or grubs. Brown patch is active during these same conditions. If you have any doubt, you can always send a sample to the diagnostic lab.

Management

Pythium thrives in water, so water management is the key to Pythium blight control. The following practices will reduce the risk of other diseases (and stresses), too:

- Improve drainage in areas where water is likely to stand for any length of time.

- Avoid overwatering, especially during hot, humid periods.

- Promote rapid turfgrass drying by proper spacing and pruning of shrubs and trees.

- Fans can improve airflow in closed-in areas where collars and approaches have a history of disease.

- Irrigate in the early morning to reduce the number of hours of leaf wetness.

- Excessive nitrogen fertilization stimulates lush growth that is more susceptible to Pythium blight. Maintain a proper balance of nutrients and avoid fertilizing during periods of Pythium blight activity.

- If active mycelium is present, avoid mowing, which can spread the pathogen.

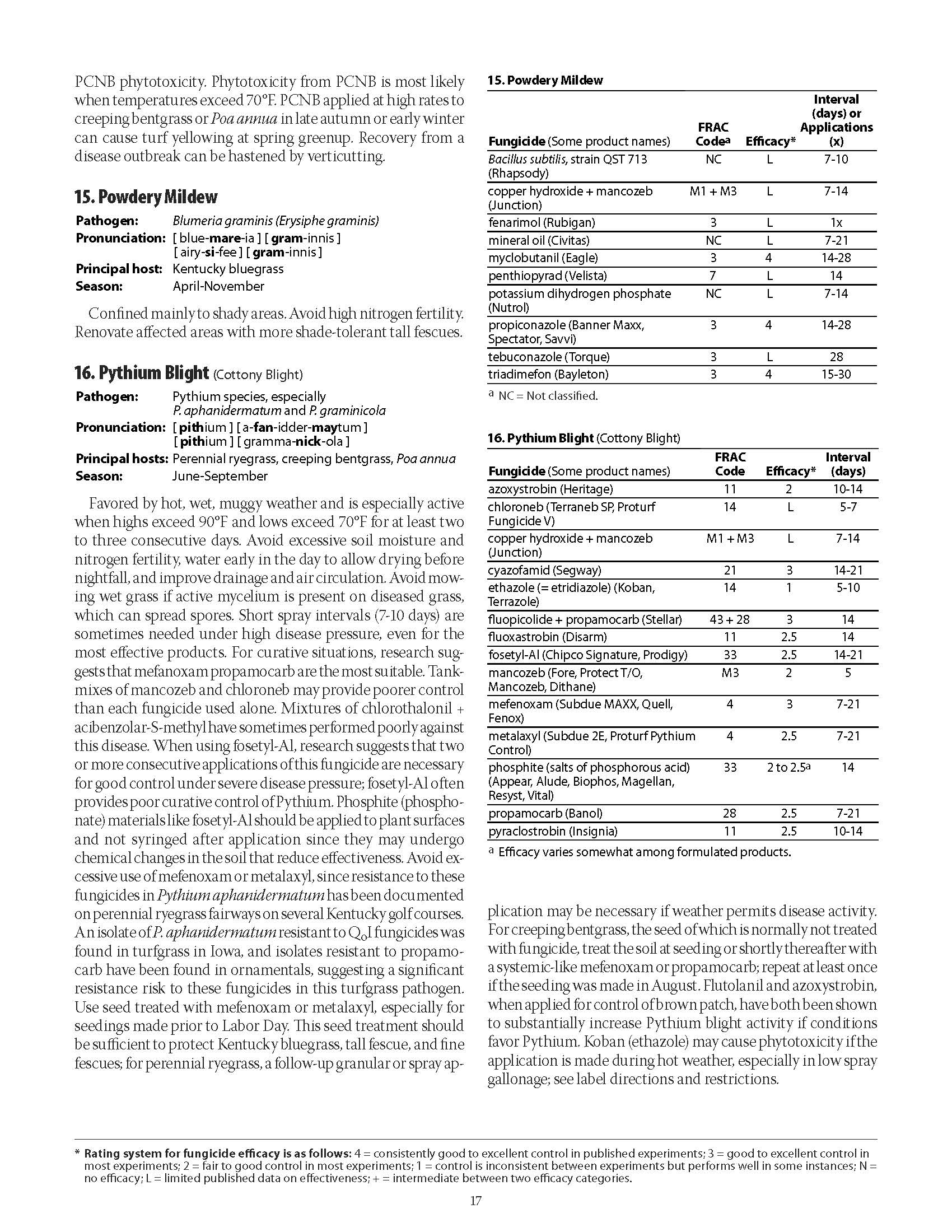

Preventive fungicide applications during the summer months may be necessary on perennial ryegrass or creeping bentgrass golf fairways.

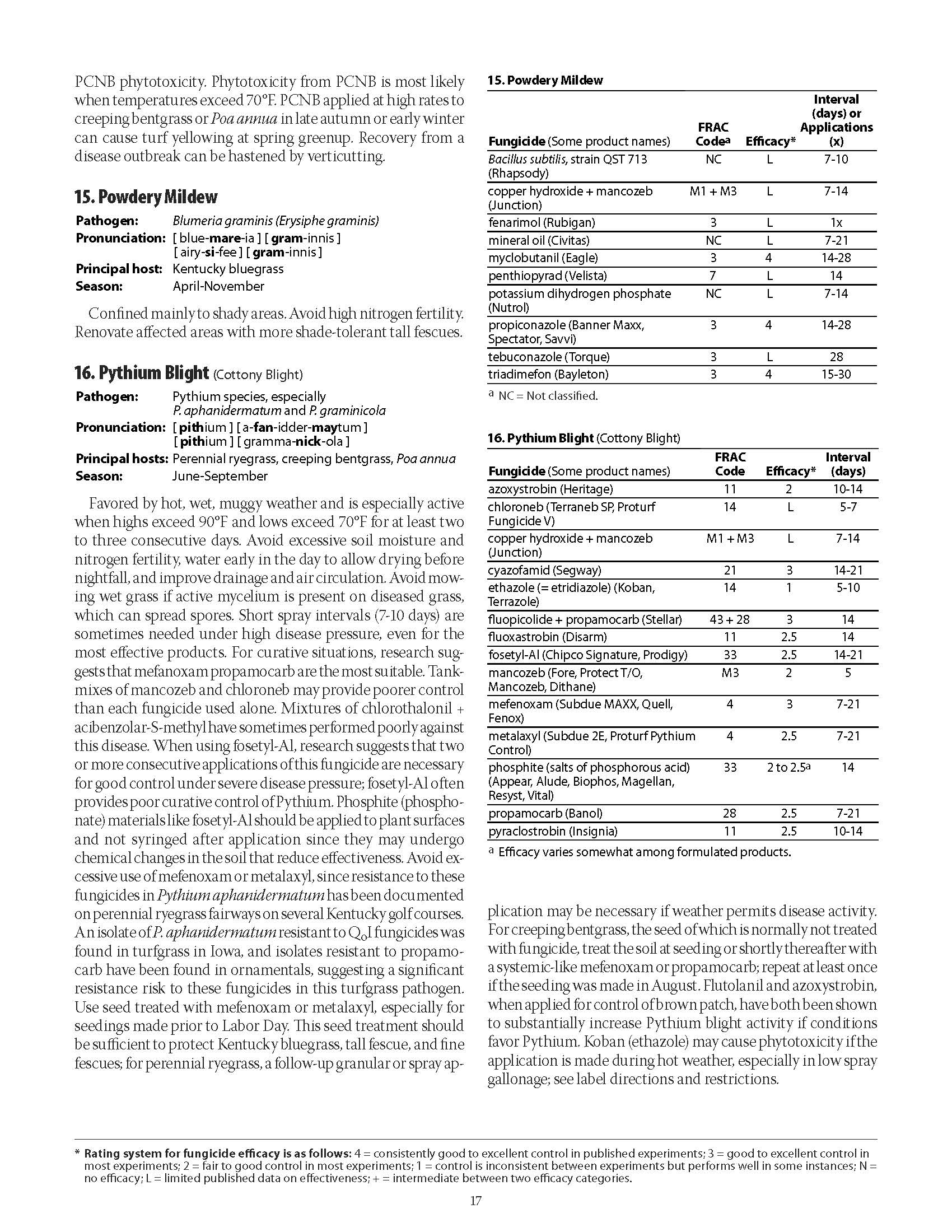

Below is the Pythium blight fungicide information from Chemical Control of Turfgrass Diseases by Paul Vincelli and Gregg Munshaw at University of Kentucky. You can click the image below to zoom. For the full guide, visit HERE.