(Megan Kennelly, KSU Plant Pathology)

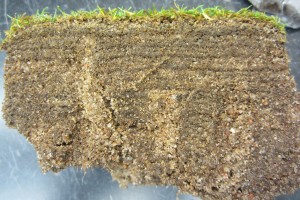

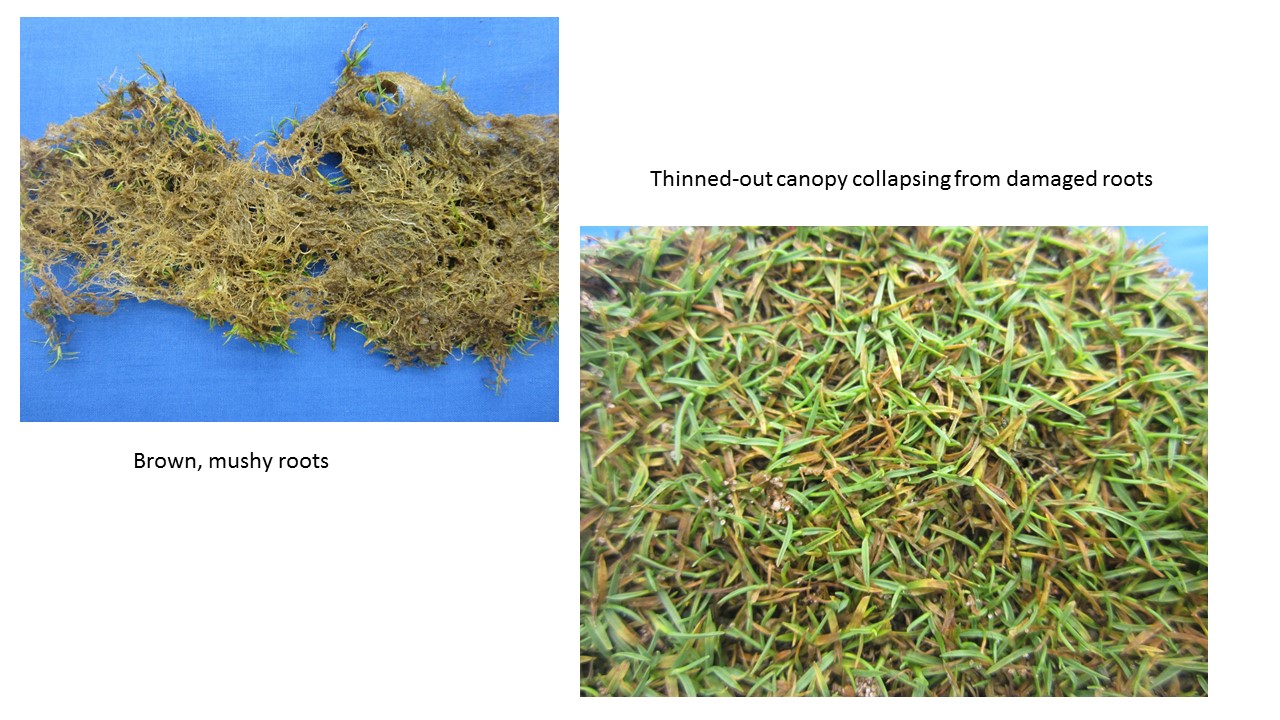

We had a sample come in with soggy roots, algae, and a lot of thinning.

Here is the root zone. Lots of organic matter holds water, which holds heat. Hot, wet roots can decline quickly.

Hot, soggy roots can’t support growth.

(I did not find Pythium root rot structures in this sample, but these same conditions can lead to that disease, too.)

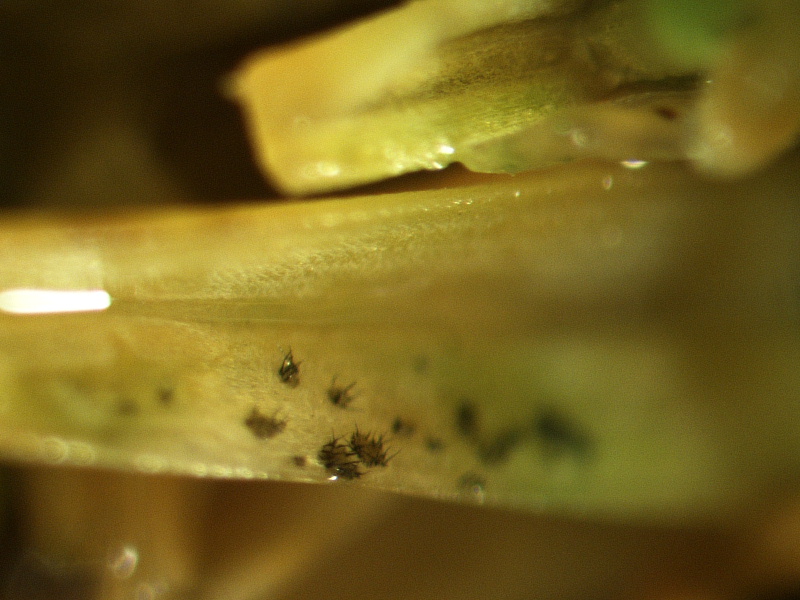

Looking closely, there was algae present. The dark green stringy stuff in the circled area is algae growing on the turf, viewed in the dissecting microscope. Algae is another indicator of wet conditions.

At closer inspection, in the compound microscope, spiny black structures were visible near the base of many declining plants that were just starting to fade from green to yellow or tan.

These structures are called setae, from the anthracnose pathogen, which is a fungus.

The publication Chemical Control of Turfgrass Diseases has a very detailed section about anthracnose, outlining many agronomic practices to reduce turf stress and reduce the threat of disease. You can find those tips at this link:

http://www2.ca.uky.edu/agcomm/pubs/ppa/ppa1/ppa1.pdf

The anthracnose section starts on page 8.

As you glance through, you may notice that many of the practices to reduce anthracnose are similar to practices to reduce overall summertime stress in putting greens, such as providing enough but not too much water, raising mowing height (even a tiny bit can make a difference), skipping mowing and rolling instead, and maintaining adequate N. You can find the whole list starting on page 6 of Chemical Control of Turfgrass Diseases which, in short, includes information about mowing height, watering, fertility, foot traffic, dew, phytoxicity warnings, and more. We highlighted those a few weeks back in another post.