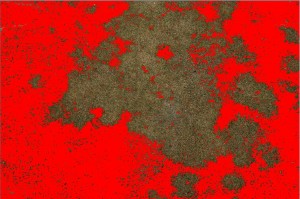

Dollar spot is active during temperatures of 65-85 F, and we definitely have had those conditions lately.

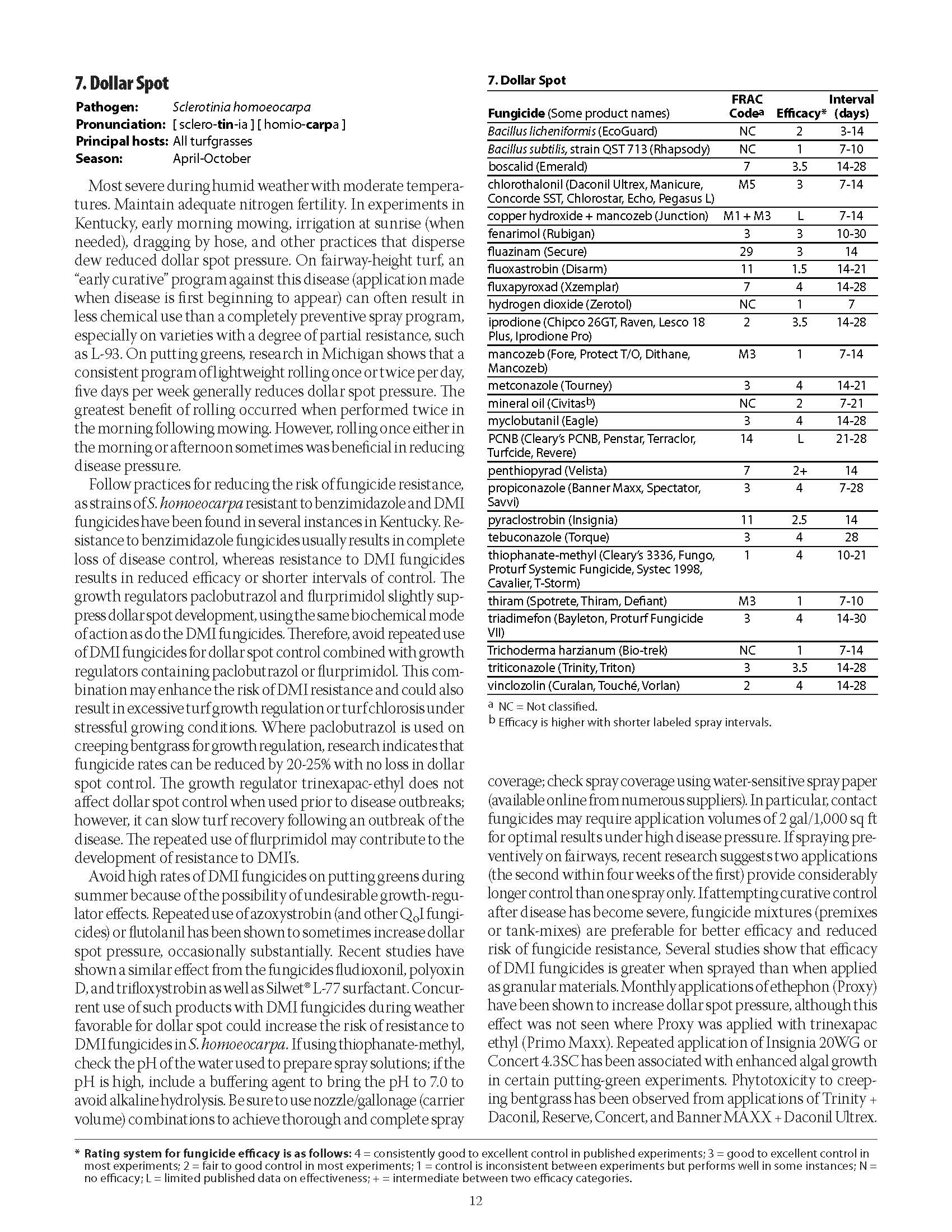

What to do? Rather than reinvent the wheel on describing potential management regimes, below is the dollar spot information from the excellent fungicide guide from University of Kentucky (for the full guide click HERE). (Oh I’m also excited to announce that one of the authors, Paul Vincelli, will be one of our speakers at the Kansas Turf Conference later this year).

But hold on – as an important side note – in a study at KSU a few years ago we found that 63 of the 65 dollar spot isolates (strains) we tested from across Kansas were fully resistant to thiophanate-methyl. (The study by my former M.S. student Jesse Ostrander was published HERE). Resistant isolates will grow through thiophanate-methyl like you didn’t do anything. I don’t think I know anyone relying on that material by itself for dollar spot, but this is just a heads up that resistance is definitely a problem for that product. I did have a conversation a year or two ago with someone using thiophanate-methyl plus a low rate of chlorothalonil and they had a lot of breakthrough. We did not test their isolates, but I’m guessing they had resistance to the thiophanate-methyl, and then the lower rate of the chlorothalonil was not enough to get them through the window they were hoping to cover. (Thiophanate methyl is a good product for some other diseases).

In addition, some of the other materials are at risk so be sure to rotate among mode-of-action groups. Some labels provide information about rotations.

What is YOUR dollar spot plan? Shoot me an email, or pop over to our Facebook account and leave a comment. I’ll share any great tips that you share.

Okay – now here is the guide. You can click the images below to make them bigger.