After last week’s posts, I got several follow-up questions by phone and email on how to use moisture meters. Dr. Bremer is our microclimate guru, so I asked him to provide some pointers. – Megan Kennelly

How much water is too much or too little for your greens?

By Dale Bremer

As Dr. Jack Fry discussed in his recent article on this blog Good Water Management Will Help Get Greens Through Summer Stress, too much or too little water can be detrimental. I thought I would follow up with a few practical tips on how to determine the correct amount of water for your green using a soil moisture sensor that determines volumetric water content. The most common soil moisture sensor is probably a TDR (time domain reflectometry) such as the one shown in Figure 1. Keep in mind that different depths (lengths) of probes are available, and that you are primarily interested in measuring soil moisture in the root zone; any moisture that is below the root zone is unavailable to the plant. The depth of the root zone may vary during the summer (shallower in midsummer, deeper in spring and fall), but a good compromise would probably be the 3 inch probes.

(Figure 1)

Ideally we should avoid constantly saturating soils with water. Instead, allow them to dry down to a predetermined level of soil water content just before the onset of drought stress symptoms. By definition, soils are saturated when 100% of the soil pore volume is filled with water. After irrigation, the soil will eventually reach field capacity, which is the amount of water remaining in the soil after free drainage has ceased. At field capacity, soils have good aeration but also have sufficient water for plant use. General guidelines for the volumetric water content at field capacity are 15-20% in sandy soils, 35-45% for loam soils, and 45-55% for clay soils (1).

On the other end of the scale, permanent wilting point is the soil water content when plants wilt and don’t recover when the soil is rewetted. Obviously this should be avoided in a green! Textbook values for volumetric water content at the permanent wilting point are 5-10% for sandy soils, 10-15% for loam soils, and 15-20% in clay soils.

However, for a number of reasons soil water content values at field capacity and permanent wilting point may vary from the textbook values for your green. This could be caused by differences in sand particle size, organic matter content, age of a green, etc.

A simple way to determine how much water to apply to your greens is to calibrate your soil moisture probe to your soils with the following steps:

- Irrigate the turf thoroughly, then take readings with your soil moisture sensor one hour later. Measure in several spots around your green, perhaps even in a grid pattern as you see fit.

- Take readings twice daily and note visual stress symptoms of the turf.

- Continue taking readings until turf shows symptoms of drought stress.

- Once these levels have been determined, use them help guide future irrigation events.

- Calibrate for each soil type.

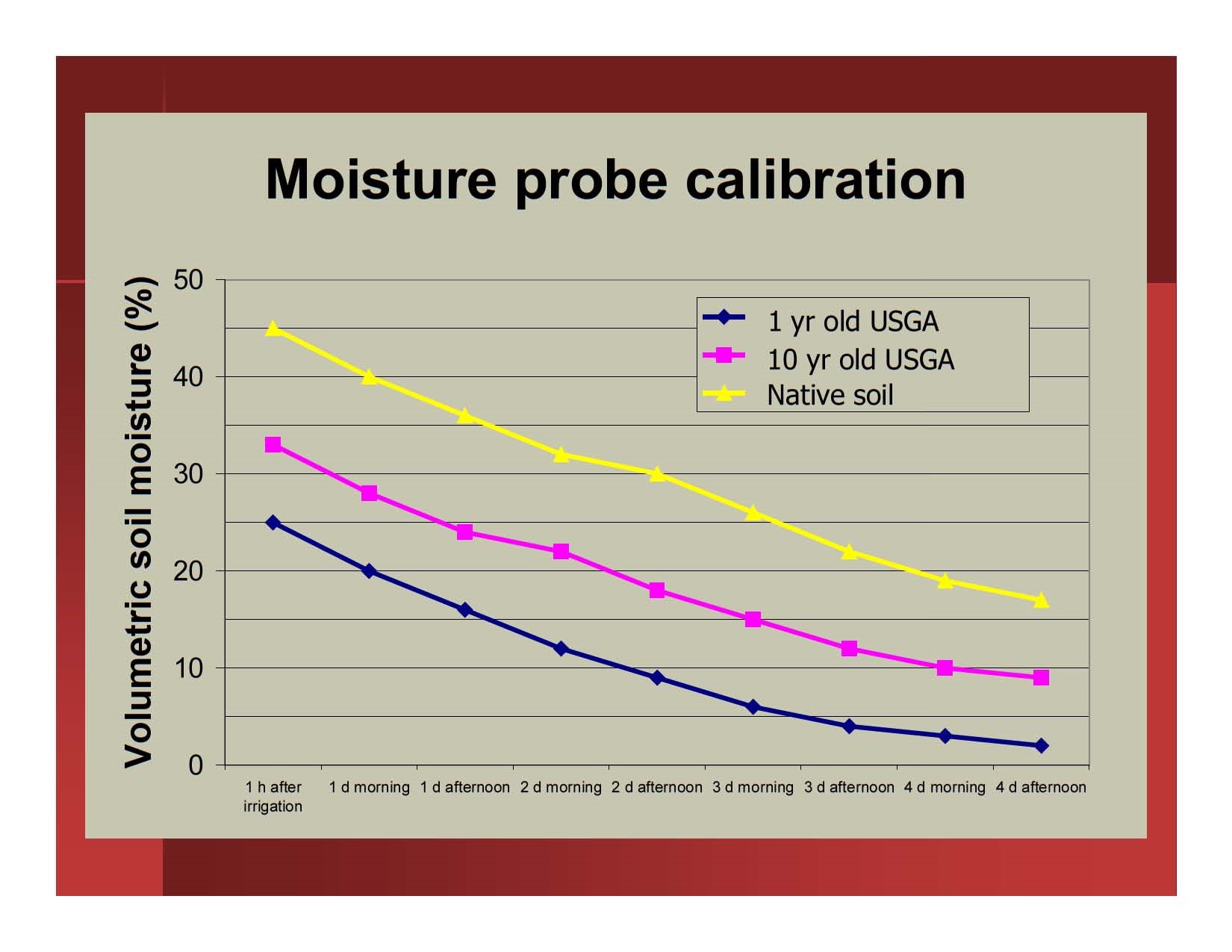

My colleagues at the University of Arkansas (Doug Karcher and Mike Richardson) (2) used this method on native soils and on 1-year old and 10-year old USGA greens and came up with the dry down curves in Figure 2.

Although soil moisture levels in the 10-year old green are higher than the 1-year old green, it is likely that drought symptoms begin at a higher soil moisture content in the 10-year old green; the same is likely for the native soil. This illustrates why it is a good idea to calibrate separately for different soils and for greens that may differ in age. It’s also important to note that drought threshold levels may change through the year, as the root system changes (as alluded to above). For example, a shallow root system in midsummer may require that irrigation be applied at a higher soil water threshold because roots are not able to “mine” water deeper in the soil as they may have earlier in the growing season.

References: