This yucky summer weather just keeps going. The past few days have been the most humid I have experienced in a while. Hot and humid = Pythium weather. We’ve mentioned foliar Pythium a few other times during this stressful summer of 2016. (As a reminder, foliar Pythium is distinct from root Pythium… which we’ve also discussed a few times!)

In the past we days we received a couple of samples of Pythium foliar blight (also called Pythium cottony blight). One was from a perennial ryegrass golf course fairway.

In the photo above you can see the greasy, matted down appearance of the turf. With a handlens, or even just with the naked eye if you looked closely, mycelium was present. In the microscope it was clearly Pythium (see the tall fescue pics below).

Here are some shots of the ryegrass in the field:

The second sample was from a tall fescue home lawn. Usually we think about Pythium on ryegrass or creeping bentgrass, but it can attack other cool-season turfgrasses. Tall fescue has more potential to recover than perennial rye or bentgrass. In 11 years, I have seen it on tall fescue only 1 or 2 two times before.

Below is a photo of the greasy, matted-down tall fescue turf. After incubating overnight in a plastic box with wet paper towel the mycelium was present.

In the microscope, the pathogen was clearly distinguishable as Pythium.

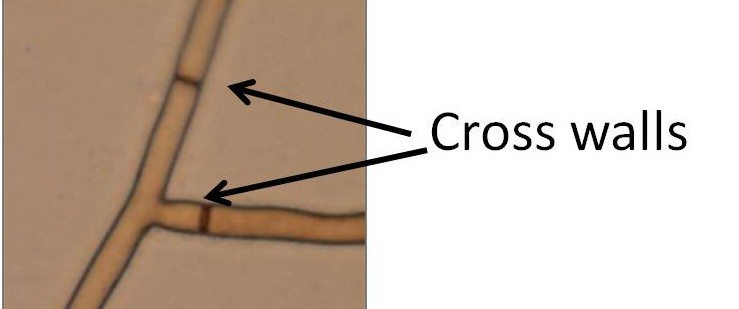

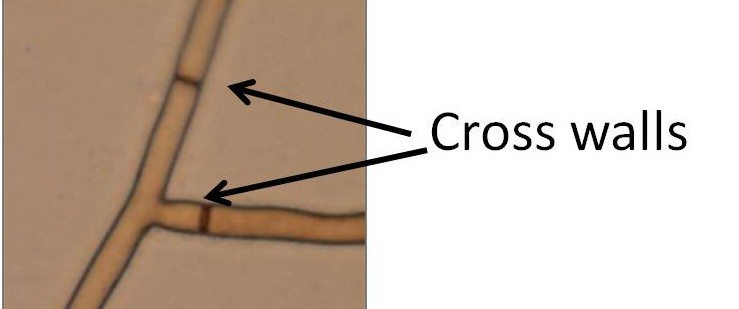

Just as a comparison, check out the strong crosswalls that are found in the brown patch pathogen, Rhizoctonia solani:

Here is a shot of the site, where it looks like the Pythium was tracked along with a mower:

The pattern is different from brown patch, and brown patch lesions were not present. I have seen weird tracking patterns with fertilizer burn or other chemical injuries, too. It can be challenging to know what is what. If you have any doubt, send in a sample, and email some photos.

Pythium thrives in wet conditions, so avoid overwatering. Water deeply and infrequently, and avoid watering in the evening. Improve drainage and try to increase airflow and sunlight. Avoid overfertilizing – Pythium loves an overly lush lawn. As a bonus, those practices will also reduce the risk of brown patch.

Pythium is not a true fungus, it is an oomycete. The most effective fungicides for Pythium are the ones specifically for oomycetes. There is a comprehensive list here, from the Chemical Control of Turfgrass Diseases publication from University of Kentucky (click the photo to zoom in):

There is some more excellent information, photos, and management tips here:

http://extension.missouri.edu/p/IPM1029-17#Pythiumfoliarblight

Brown patch is still active out there (it’s a little faint in the pic, but it’s there):

And dollar spot is active, too (mixed in with more brown patch):