–Dr. Robert Bauernfeind

An old friend revisited – Wooly maple/briar aphids (WMBA)

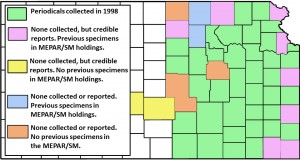

It has been a number of years since I have had occasion to address wooly briar/maple aphids. And matching dates of past encounters, the timing is right on (in 2007, June 1, and in 2009, May 29).

The inclusion of two very different host plants might have a person asking, “Well, are they on maple or are they on briar?” In fact, both a primary woody host (maple) and an unrelated secondary/alternate herbaceous host (brier) are required for these aphids to complete their seasonal life cycle.

Despite their rather simple and familiar appearance, some aphid species (such as wooly maple/brier aphids) have very unusual and complex reproductive adaptations. While most people are aware that the aphids which they encounter in their gardens and landscape plantings are all females which (in the absence of males) reproduce parthogenically by giving birth to living offspring, sexual forms are required for mating purposes and the eventual production of overwintering eggs. This is where maple trees come in — where (in the Fall) WMBA deposit overwintering eggs.

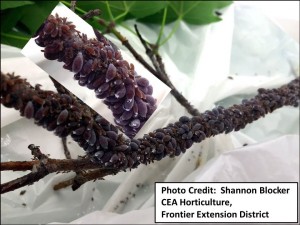

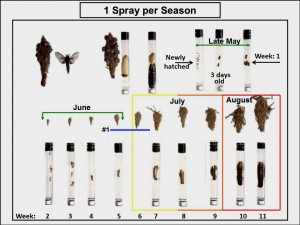

Thus, beginning in Spring, each 1st generation aphid emerging from an overwintered egg is a wingless female called a fundatrix (foundress-of-a-colony). The offspring of each succeeding generation (all females, called fundatriginae) also produce living young. These aphids eventually become overcrowded as they colonize twigs and branches.

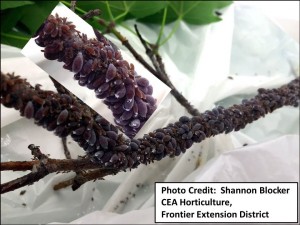

While the above-pictured aphids appear to be “normal aphids”, they aren’t called wooly aphids for no reason. That is, these aphids possess specialized wax-producing glands. And at some point, they will begin producing white flocculent strands which provides them with their “wooly appearance”.

While not being sure of the exact stimulus at work, at some point, possibly overcrowding and constant touching/bumping-into-each-other “triggers” an internal response mechanism promoting wing production in developing aphids. By mid- to late June, those aphids (again, all females which are now called exules) emigrate from their woody maple host to their alternate herbaceous host which, in Kansas, would likely be the plentifully-abundant greenbrier.

Upon reaching the summer host, exules deposit their offspring (you guessed it, all wingless females) which in turn account for additional summer generations on their briar hosts. Upon entering Fall, shortened daylight hours hourst, decreased temperatures or a combination of both set off another change in aphid forms (now called sexuparae) of which there are two types: Gynoparae are winged females which emigrate back to the primary host where they produce wingless females called oviparae; and androparae are winged females which emigrate back to the primary host where they produce wingless males. Males mate with oviparous females which then deposit the aforementioned fertilized overwintering eggs.

Now to the discussion on wooly maple/briar aphids that most readers care about. Are they harmful? Is there a need to control them?

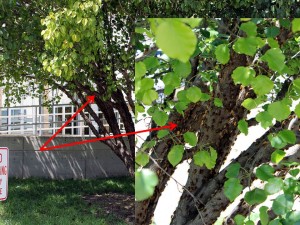

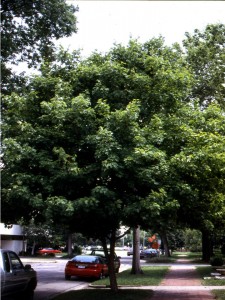

The only real complaint leveled against wooly maple/briar aphids revolves around the “sticky mess” which they are responsible for. WMBA congregate on the twigs and branches of the different varieties of sugar maples. They insert their piercing-sucking mouthparts into the phloem elements which conduct the flow of plant juices/sap. Fairly stationary, aphids continually withdraw the sugar-rich sap. The excess juices are eliminated/excreted in the form of “honeydew”. The honeydew “rain” will coat anything beneath WMBA-infested trees — vehicles, sidewalks, driveways, house decks, picnic/patio furniture, children’s swing sets and toys, items on clothes lines, and so on. Being sticky and nutrient-rich, captured airborne fungal spores can proliferate into unsightly accumulations of dark-colored sooty mold. But other than that, trees easily withstand wooly maple/briar aphid infestations as seen below.

While insecticidal sprays and/or the use of forceful water sprays might seem called for, neither is practical in practice. And, unnecessary! By the time such infestations are discovered, within a very short period of time (2 weeks, possibly less), as described in the prior explanation of their seasonal developmental cycle, they will quickly dissipate on their own when they seek out their alternate summer host. IT IS HIGHLY UNLIKELY THAT THEY WILL FIND THEIR WAY BACK TO THE SAME TREE HOST FROM WHICH THEY IMMIGRATED —- at least by my experiences/inspections.

Maybe one last-and-legitimate gripe: handle with care. They do leave a hard-to-remove stain that might relegate good clothing to a wear-only-at-home status.