Adapted from the K-State Turf and Landscape Problem Solver

Careful turfgrass selection is an important first step in establishing, overseeding, or renovating a turfgrass. Many potential problems related to turf use, appearance, environment, insect or disease pests, and cultural practices can be avoided by properly choosing species and cultivars that best fit the situation in which the turfgrass will be grown. A turfgrass, when planted in areas where it is not adapted, often deteriorates or fails. The result of planting a turfgrass where it is not adapted is a poor-quality turf that requires excessive pesticide applications, fertilization, and replanting to retain a green ground cover. A high-quality turf may not be obtainable in this situation.

Consider these criteria when selecting a turfgrass:

- Desired quality

- Appearance – turf color, texture, density, growth habit, and uniformity

- Use – turf purpose, e. g., athletic or play surface, lawn, erosion control

- Pest resistance – turf resistance or tolerance to disease or insect pests

- Culture – turf management requirements from a time and a financial view point

- Site – turf soil and sunlight requirements compared to those of the final planting site.

Turfgrasses differ with regard to these criteria. For example, some Kentucky bluegrass cultivars form a dark emerald green turf adapted to high maintenance and light shade. This can be contrasted with buffalograss, a gray-green, low-maintenance turfgrass that performs poorly in light shade. Other differences among species and cultivars also exist regarding wear tolerance, environmental adaptation, pest resistance, and cultural requirements. Careful selection at planting time is the best way to solve potential problems in the future.

Generally, the cost of planting turfgrasses, whether from seed, sod, plugs, sprigs, or stolons, should be of minimal concern. In most normal plantings, the cost difference between poor-quality and high-quality seed or vegetative propagules is small, and the time and money spent trying to produce high-quality turf from low-quality seed or vegetative material can often become great. The long-term benefit of planting high-quality turfgrasses in appropriate conditions is a healthy, cost-effective, quality turf.

- Turfgrass Categories Based on Function, Maintenance, and Quality

- Cool Season and Warm Season Species

- Cultivars and Varieties, and Blends and Mixes

- Turfgrass Species for the Midwest

- Other Species Occasionally Used in the Midwest

The effort and time expended selecting the right grass species, mixes, and/or blends will be well spent. Consider the site, use, desired appearance, and management the turf will receive when selecting the species combination. Then select cultivars that best fulfill the desired outcome. Often, there may be more than one “good fit” between turf species, mixes, and/or blends for the specific situation. In such cases, cost and availability may become important factors in the final decision. Plant only high-quality propagules (e. g., seed, sod, plugs). When these steps are followed and the actual turf is planted, many potential problems will be reduced, or in the best of situations, eliminated.

The 73rd annual Kansas Turfgrass and Landscape Conference, held November 29 & 30 (Wednesday and Thursday), 2023 at the Hilton Garden Inn, Manhattan also hosts a trade show to see all the latest products and supplies from local and national vendors.

The 73rd annual Kansas Turfgrass and Landscape Conference, held November 29 & 30 (Wednesday and Thursday), 2023 at the Hilton Garden Inn, Manhattan also hosts a trade show to see all the latest products and supplies from local and national vendors. Vendors will have a booth with representatives present for the following companies:

Vendors will have a booth with representatives present for the following companies: Interested in being part of the trade show as an exhibitor or as sponsor for the event?

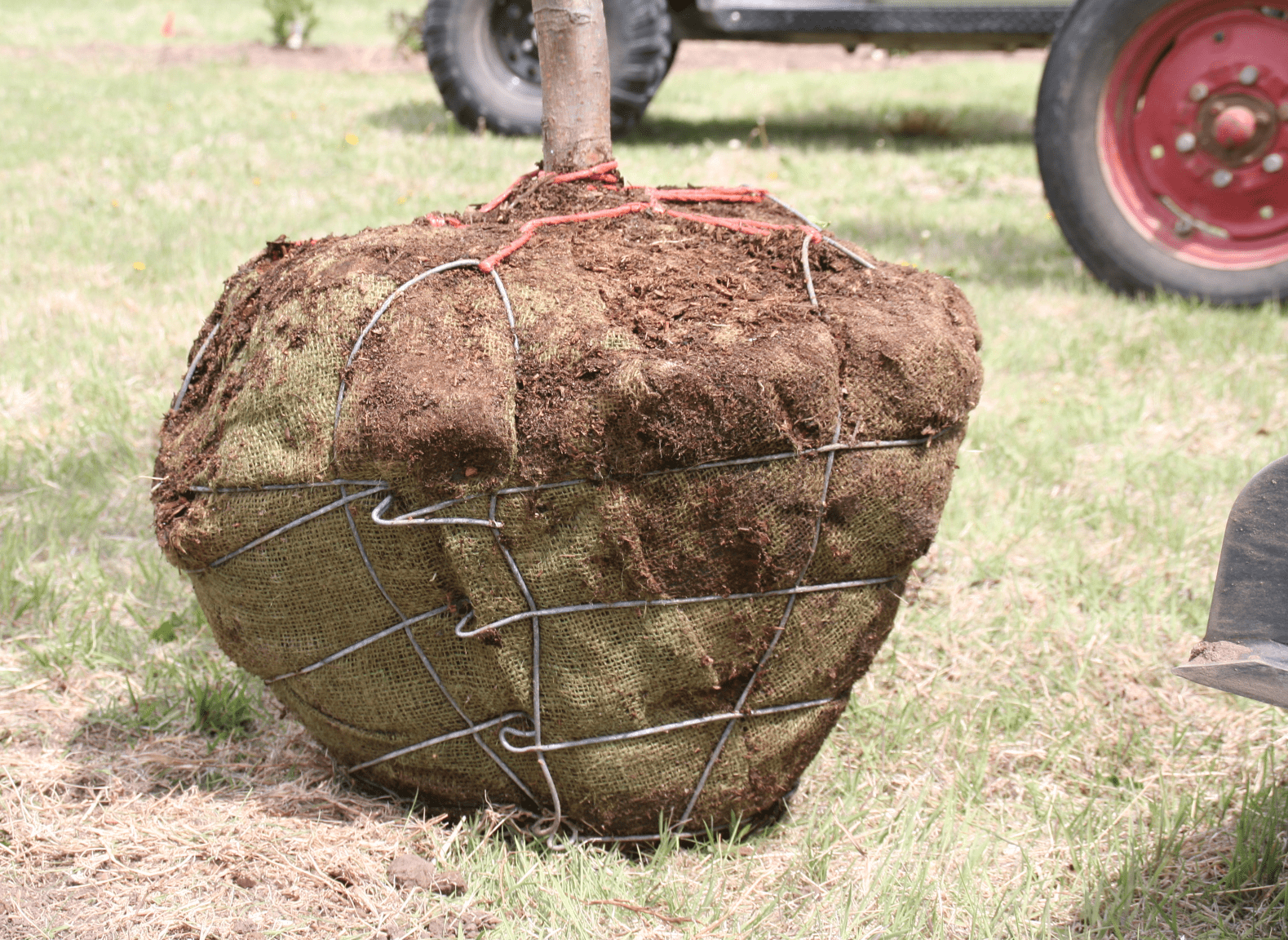

Interested in being part of the trade show as an exhibitor or as sponsor for the event?  Last, there is the plant side. Is fall a good time to plant a new tree or shrub? Yes, and here is why. The primary job of a newly planted tree or shrub is to grow roots for survival. New roots are necessary for balled and burlapped plants to replace the ones lost during the harvest process at the nursery. If it’s a container plant, new roots are necessary to explore the soil and find nutrients and moisture necessary for long term survival. For the first year of a new plant’s life, it’s all about the roots!

Last, there is the plant side. Is fall a good time to plant a new tree or shrub? Yes, and here is why. The primary job of a newly planted tree or shrub is to grow roots for survival. New roots are necessary for balled and burlapped plants to replace the ones lost during the harvest process at the nursery. If it’s a container plant, new roots are necessary to explore the soil and find nutrients and moisture necessary for long term survival. For the first year of a new plant’s life, it’s all about the roots! Trees planted in spring have only a few weeks of peak root growth before Mother Nature unleashes the environmental stresses that come with summer weather. However, trees planted in fall have the long fall and early winter season to grow roots before they go dormant. As the soil warms in spring, they get another season of root growth prior to the stress of summer in Kansas. Fall planted trees, therefore, have the advantage of two full seasons of root growth before summer drought and heat strike. It’s not too late. As long as the soil isn’t frozen at your planting site, you can still get plants in the ground. So is spring a bad time to plant? No, spring is a great time to plant. Those trees just need a little more TLC during that first summer than fall planted trees.

Trees planted in spring have only a few weeks of peak root growth before Mother Nature unleashes the environmental stresses that come with summer weather. However, trees planted in fall have the long fall and early winter season to grow roots before they go dormant. As the soil warms in spring, they get another season of root growth prior to the stress of summer in Kansas. Fall planted trees, therefore, have the advantage of two full seasons of root growth before summer drought and heat strike. It’s not too late. As long as the soil isn’t frozen at your planting site, you can still get plants in the ground. So is spring a bad time to plant? No, spring is a great time to plant. Those trees just need a little more TLC during that first summer than fall planted trees.