By Ross Braun, Ph.D., Kansas State University

It is September, winter is coming, now is the time to think about strategies to reduce winterkill risks in your warm-season turf. Last winter (2024-2025) was a tough one on some of our warm-season turfgrass managers. There were extensive reports of winterkill in zoysiagrass and bermudagrass areas on golf courses and sports fields in Kansas, Missouri, and many other areas in the transition zone. Winterkill injury is not easily identified until the warm-season grass is finished greening up in the spring (usually mid-to-late May in KS). At which point, you notice dead turf areas that never greened up with no active growth (Figure 1). What also didn’t help this spring was the below-average temperatures in May, with slightly below-normal precipitation amounts at the same time. This slowed down the spring green-up of our warm-season turfgrasses (zoysiagrass, bermudagrass, and buffalograss) and delayed the recovery needed in some areas, so that it did not start until mid-June or later. These winterkill risks will always be present, and some years we unfortunately see it more than others, but I still think warm-season turfgrasses are a solid choice for turfgrass managers in the transition zone because we can reduce a lot of management inputs (water, fertilizer, pesticides, mowing) compared to growing cool-season turfgrasses.

Over the past two years, my colleagues at other universities and I have collaborated to create “management guides” for bermudagrass and zoysiagrass managers, especially those in the transition zone that experience greater risks of winterkill. You will likely recognize that the authors include many familiar names of turfgrass scientists, as well as the wealth of knowledge they bring to these articles. These guides are written to help you identify potential vulnerable areas, the causes of winterkill, and offers solutions to prevent and recover from winterkill. I encourage you to check out these articles; they are both “open access,” meaning the authors have already paid for them to be freely available to the public (not behind a paywall). You can read them online or download each as a PDF to read on your computer or phone. I hope these management guides assist in decision-making and help to reduce potential winterkill risks in warm-season turfgrass systems.

Management strategies for preventing and recovering from zoysiagrass winterkill https://doi.org/10.1002/cft2.70050

Management strategies for preventing and recovering from bermudagrass winterkill https://doi.org/10.1002/cft2.20302

It should be neither too wet nor too dry, and the soil should crumble fairly easily when worked between your fingers. Go over the lawn enough times so that the aeration holes are about 2 inches apart.

It should be neither too wet nor too dry, and the soil should crumble fairly easily when worked between your fingers. Go over the lawn enough times so that the aeration holes are about 2 inches apart.

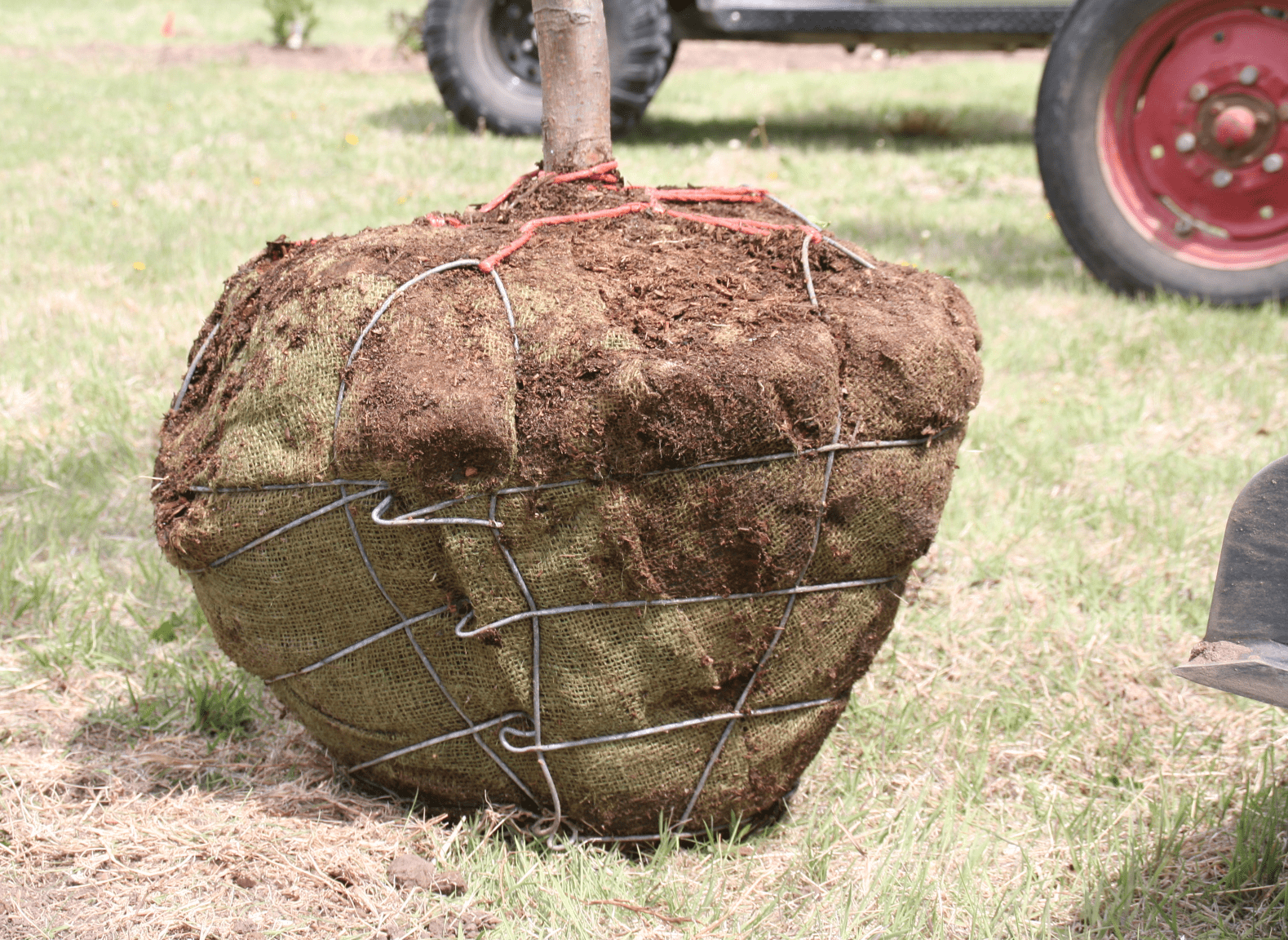

Last, there is the plant side. Is fall a good time to plant a new tree or shrub? Yes, and here is why. The primary job of a newly planted tree or shrub is to grow roots for survival. New roots are necessary for balled and burlapped plants to replace the ones lost during the harvest process at the nursery. If it’s a container plant, new roots are necessary to explore the soil and find nutrients and moisture necessary for long term survival. For the first year of a new plant’s life, it’s all about the roots!

Last, there is the plant side. Is fall a good time to plant a new tree or shrub? Yes, and here is why. The primary job of a newly planted tree or shrub is to grow roots for survival. New roots are necessary for balled and burlapped plants to replace the ones lost during the harvest process at the nursery. If it’s a container plant, new roots are necessary to explore the soil and find nutrients and moisture necessary for long term survival. For the first year of a new plant’s life, it’s all about the roots! Trees planted in spring have only a few weeks of peak root growth before Mother Nature unleashes the environmental stresses that come with summer weather. However, trees planted in fall have the long fall and early winter season to grow roots before they go dormant. As the soil warms in spring, they get another season of root growth prior to the stress of summer in Kansas. Fall planted trees, therefore, have the advantage of two full seasons of root growth before summer drought and heat strike. It’s not too late. As long as the soil isn’t frozen at your planting site, you can still get plants in the ground. So is spring a bad time to plant? No, spring is a great time to plant. Those trees just need a little more TLC during that first summer than fall planted trees.

Trees planted in spring have only a few weeks of peak root growth before Mother Nature unleashes the environmental stresses that come with summer weather. However, trees planted in fall have the long fall and early winter season to grow roots before they go dormant. As the soil warms in spring, they get another season of root growth prior to the stress of summer in Kansas. Fall planted trees, therefore, have the advantage of two full seasons of root growth before summer drought and heat strike. It’s not too late. As long as the soil isn’t frozen at your planting site, you can still get plants in the ground. So is spring a bad time to plant? No, spring is a great time to plant. Those trees just need a little more TLC during that first summer than fall planted trees.