By Lucky Mehra

When it comes to plant health, physical samples are best. However, sometimes it is not practical to send physical samples, such as with large trees or shrubs. A digital sample can be a good alternative or a good first step. By ‘digital sample’ we mean submitting digital images of the plant problem to the KSU plant disease diagnostic clinic.

Consider the following tips to take the photos and provide all the relevant information to help us diagnose the problem quickly and correctly.

Pictures

The main component of a ‘digital sample’ is the set of digital images itself. Take the following types of pictures to help us understand both the ‘big’ and ‘small’ picture of the problem. Make sure that the plant or plant part is in focus when taking pictures. Some phones are pretty good at auto focus, but most of the time you will need to tap on the screen at the point of interest to guide your camera to focus at a particular point.

- Take pictures from a distance to give us the landscape view or the ‘big picture view’. It should include the whole tree/shrub along with neighboring plants (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1. The Hawthorn tree in the foreground has leaf spots. This image is to give an overall view of the landscape. For example, proximity of the tree to the concrete and adjoining trees.

- Photo of the affected plant(s) i.e. the plant(s) showing the problem.

- Photo of the affected plant part, whether it is leaf, flower, stem, twig, or root (FIg. 2).

Fig. 2. Affected leaves of the hawthorn tree.

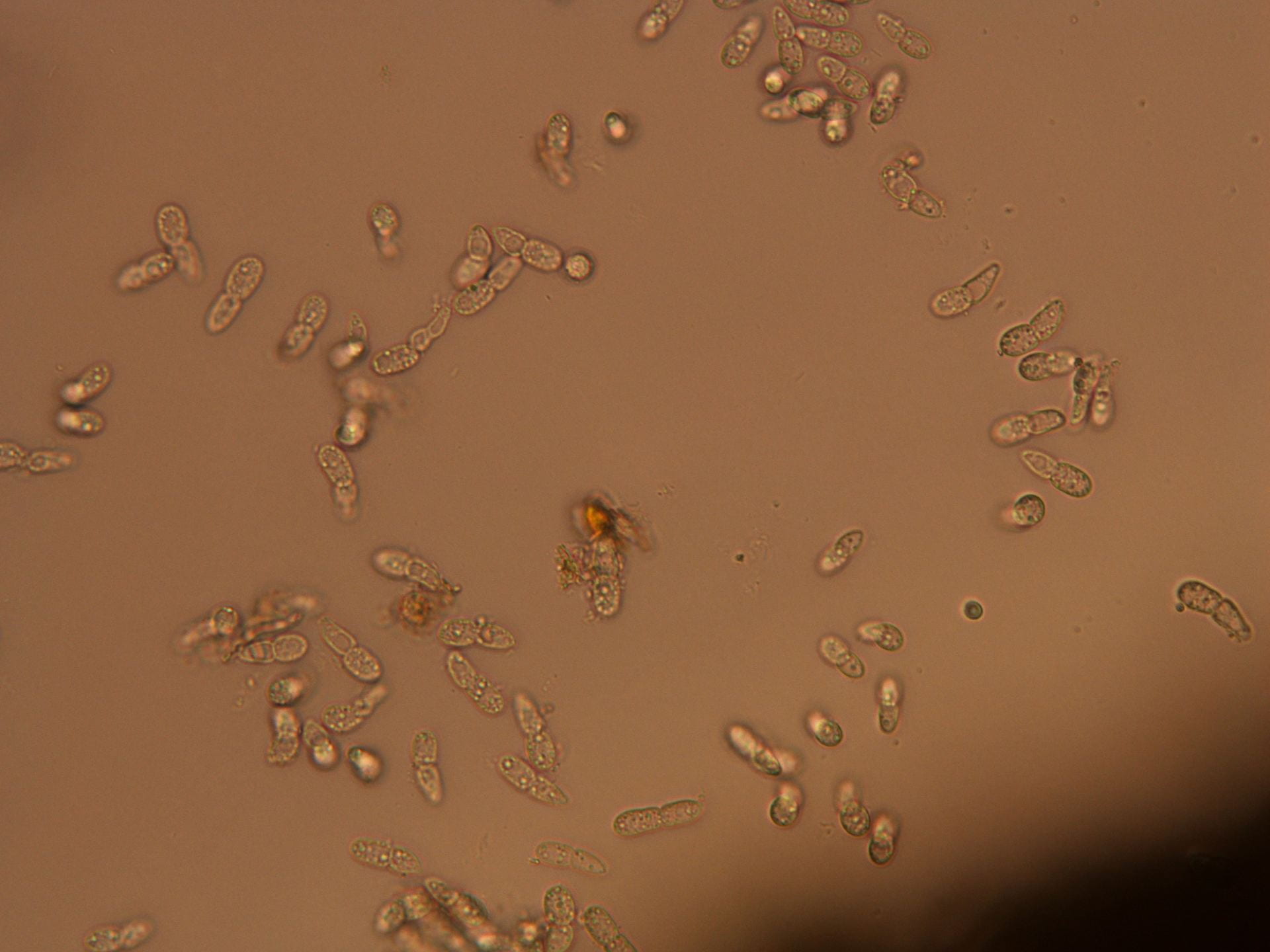

- Try to take a close-up shot of the problem symptoms (Fig. 3). If there are signs (actual parts of the pathogen i.e. fungal mycelium or other structures) present on the plant part, try to zoom in, tap to focus, and then take the photo. Take multiple photos to ensure that you will have at least a few good quality ones. If you have access to a microscope, you can bring the affected plant part to your home or office and focus it under the microscope. With some patience, you can also take really good macro shots with your phone through the eyepiece lens. Many of our students take photos this way in the lab.

Fig. 3. An example of close-up images of a hawthorn leaf (top side of leaf on the left, and underside of leaf on the right) with yellow spots taken with a phone camera, without any additional lens attachment.

Additional essential information

Sometimes, the plant problem is very peculiar, and it is easy to identify by just looking at the photos you submit (e.g. yellow spots on hawthorn leaves shown above are the symptoms of Cedar-hawthorn rust); however, most of the time it is not possible to diagnose a problem only based on photos. We need much more information from you to help us with the correct diagnosis. Provide as much information as you can. Please see below for the type of information that will be useful to us when making the diagnosis.

Site history and pattern

Make sure to provide information about the site where the shrub or tree is located. That information may include soil type if known, soil pH, slope, distance to the concrete sidewalk or road etc.

Are there any drainage problems? Is this the only plant affected? Are other plants of the same species affected? If yes, what is the pattern of these plants in the landscape i.e. is there a cluster of affected plants or the distribution is random? Are other plant species affected?

Plant pattern

Tell us about the affected plant part whether it is leaf, stem, flower, twig, stem or root. Additionally, report the location of symptoms on the plant. Some problems tend to occur on younger leaves, others are specific to older leaves. All this information can help us rule out some issues and narrow down the diagnosis.

Timing of the symptom appearance.

Was there any weather event such as temperature (too hot or too cold) or moisture extremes (e.g. heavy rainfall) prior to the symptom development. We can download these data from a local weather station as well, however, rainfall events can be non-uniform over the whole area covered by a weather station. So if you have onsite information about the weather data, report it to us.

Chemical history

Any history of chemical or fertilizer application should be provided. This can help the diagnostician in figuring out if the problem is arising due to chemical exposure or due to a biotic agent.

Iris leaf spot is not an easy disease to clean up because it overwinters in the residue. So the first step for management is to clean up the flower bed in the fall after frost has killed the tops. This will help to reduce the amount of disease that is carried over. Unfortunately it won’t get rid of the disease. If the planting is old and crowded, digging them up and respacing them will improve air flow. This can help to reduce disease severity.

Iris leaf spot is not an easy disease to clean up because it overwinters in the residue. So the first step for management is to clean up the flower bed in the fall after frost has killed the tops. This will help to reduce the amount of disease that is carried over. Unfortunately it won’t get rid of the disease. If the planting is old and crowded, digging them up and respacing them will improve air flow. This can help to reduce disease severity.