–by Dr Bob Bauernfeind

A second spark was in the form of an e-mail received from Dr. Sarah Zukoff at the Southwest Research and Extension Center in Garden City: carpenterworms.

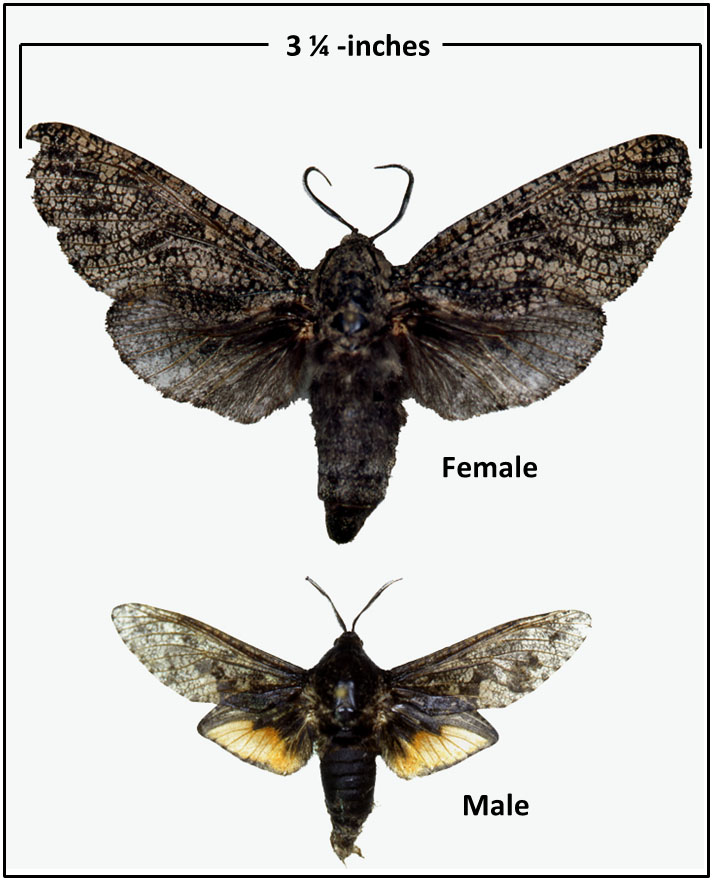

Over many years of operating blacklight traps throughout Kansas, I have collected hundreds of carpenterworm moths. Female moths are large (wingspread up to 3 ¼ inches) and rather drab in appearance. Male moths are smaller (wingspread ½ that of the female) and also appear drab when wings are folded. But upon spreading the forewings and exposing the hindwings, the coloration and pattern of the male’s hindwings is strikingly different from that of the female.

As common as the moths are, I have only been “on-site” once. On 10/04/2010, I arrived in McPherson in response to a resident’s request. It was apparent that carpenterworms were at work. They were creating tunnels and expelling large amounts of sawdust (a combination of wood chewings and frass) which was accumulating at the base of a large green ash situated next to a house. Given that carpenterworm life cycles are lengthy (2-3 years depending on environmental factors), the currently-present carpenterworms originated from eggs deposited in 2007 or 2008.

This tree has been under attack over a period of years as seen by extensive scarring of the bark. While the scarred bark surface presented a “healed appearance”,

it concealed the extreme underlying damage accrued by previous carpenterworm activities.

While carpenterworms seldom kill tree hosts, their extensive feeding damage reportedly can structurally weaken trees resulting in the breakage/falling of limbs and entire trees. This was the concern of the homeowner given the proximity of the tree to her house. Granted that while I am not a bona fide “tree person”, my unqualified assessment was that the tree was structurally sound. The local arborist disagreed and recommended removal. I was not present at the time of removal (December), but I did travel back shortly thereafter. The size of the borer tunnels were impressive in a cross section from the trunk. Yet, it was interesting to note that despite the ominous presence of carpenterworm activities, their tunneling activities were dismissive in comparison to the amount of solid wood. The tree was structurally sound.

A little background regarding carpenterworms. Although most people probably are not familiar with carpenterworms, they are not a “new pest species”. We are approaching the second century anniversary of the year in which they were first reported to damage trees (1818). Carpenterworms attack a wide variety of tree species including ash, birch, black locust, cottonwood elm, maple, oak and willow. Fruit trees such as apricot and pear are also listed, and possibly (by extension) would also include most any fruit tree species.

The carpenter worm developmental life cycle varies depending on their geographical latitude: 1-2 years in the Deep South to 4 years in the Northern States and southeast Canada. In Kansas (being somewhat in the middle), the carpenterworm life cycle probably lies between 2-3 years. However in any given year, overlapping generations are likely to occur.

Given a 3-year scenario: Female carpenterworm moths reportedly produce between 200 and 1,000 eggs which are preferably deposited in protected/hidden sites (bark crevices, under lichens, and near wounds and scars) on tree trunks and main/larger limbs. Newly hatched larvae penetrate the bark, or enter through existing openings. They create shallow tunnels in the inner bark in which they overwinter. Feeding resumes in the spring at which time larvae extend and widen tunnels. Moving inward, they form upward-slanting tunnels into and through the sapwood and then into the heartwood where they form vertical tunnels in which they overwinter. In the third summer, the vertical tunnels are extended (up to 9 inches long) and expanded (over ½-inch diameters). In the fall, larvae return to the area of the exit hole in the bark and produce a silken layer which lines the gallery walls and forms a curtain over the exit hole. Larvae then overwinter a final time. In spring, larvae move close to the exit hole and are transformed into pupae. Just prior to moth emergence, pupae will wiggle and force their way through the silken curtain. With the anterior of pupae thusly exposed, moths emerge outside of the tree where they will harden and be “free” to take flight.

Carpenterworms have a negative impact on lumber production. Individual or cumulative damage associated with extensive tunneling, staining and wood decay may seriously degrade the quality and quantity of lumber from individual trees. Fortunately, however, carpenterworm distribution (and consequently damage) within fully forested lumber production areas appears to be less than that seen on open-grown shade trees, roadside trees or trees in shelterbelts and edge-of-the-woods trees.

Due to the unpredictable appearance/occurrence of carpenter worms, little can be done in a preventative sense. The presence of carpenterworms usually is detected late (the third year) in their developmental cycle when excessive sawdust accumulations catch one’s attention. While the damage has already occurred, some people will attempt to kill larvae by inserting a wire probe into the carpenterworm’s tunnel. Depending on the larva’s position in the tunnel system, this may or may not work. If a person attempts to force a stream of insecticide into the tunnel, care should be taken to avoid a backsplash of the insecticide stream. Because carpenterworms seem to prefer repeatedly attack the same tree and ignore nearby trees, the “magnet tree” can be removed, thus eliminating the major local source of carpenterworm moths.