— by Dr. Jeff Whitworth and Dr. Holly Davis

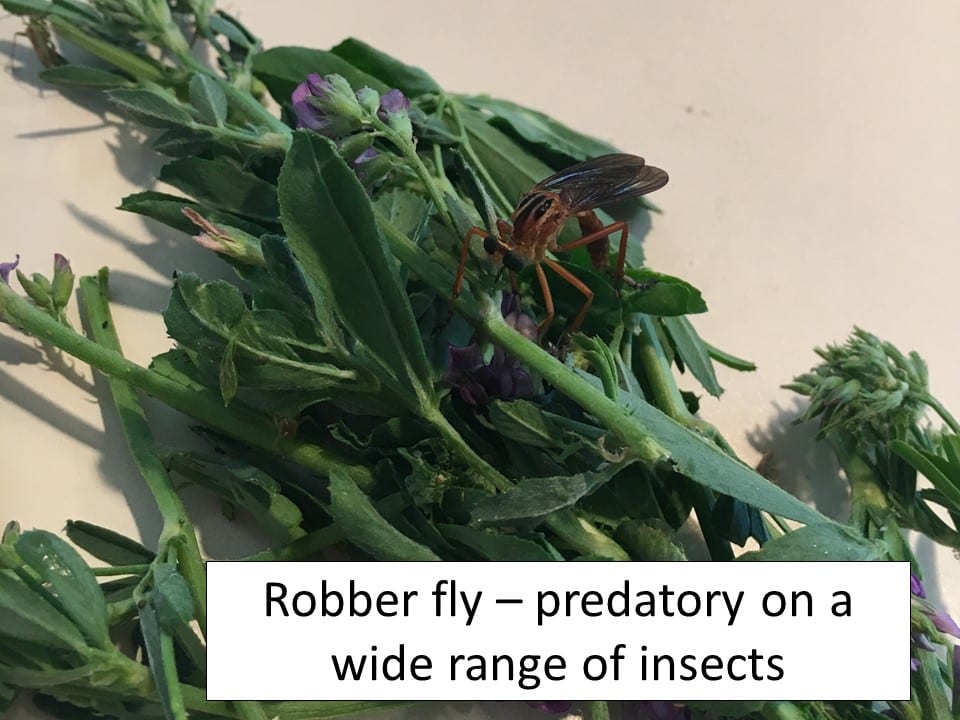

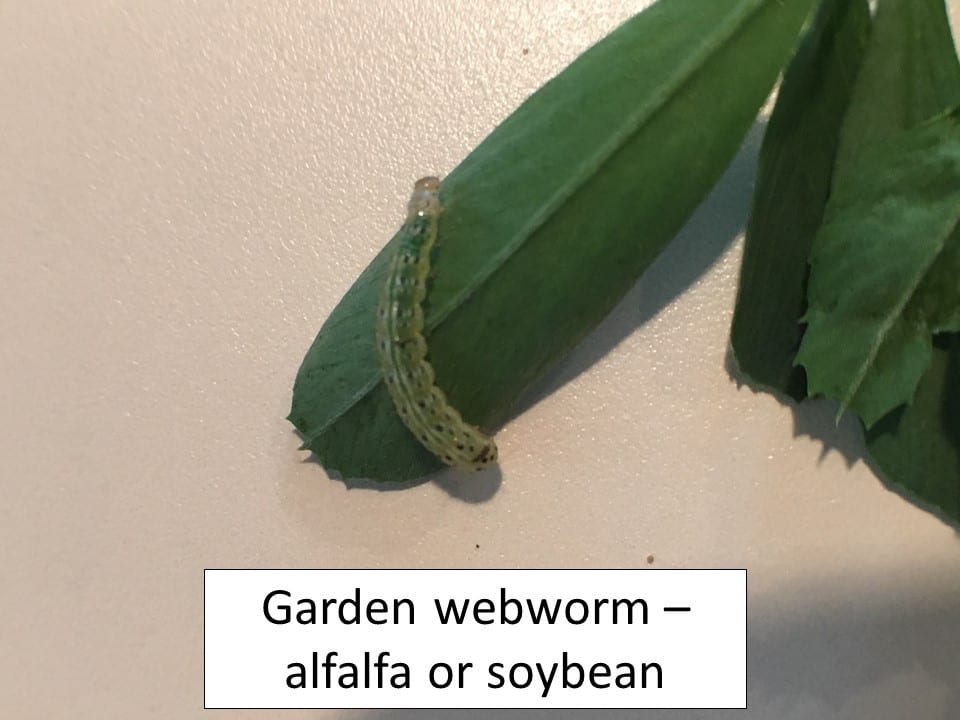

Several alfalfa fields were sampled in north central Kansas this past week. The alfalfa canopy remains an excellent habitat for many insects, especially those fields not treated for alfalfa weevils this year. Many of these insects are beneficial.

Very few pests, or potential pests, were detected although there were a few potato leafhoppers present. These small, lime green, herky-jerky, moving pests are apparently just beginning to migrate into KS, as we didn’t find any earlier in the week, and now are only finding a couple of adults. For more information relative to potato leafhopper management, please refer to the KSU 2018 Alfalfa Insect Management Guide: https://www.bookstore.ksre.ksu.edu/pubs/mf809.pdf