–by Raymond Cloyd — Horticultural Entomology

Month: September 2021

Insect Diagnostics 2021 Season Summary

–by Anthony Zukoff — Southwest Extension and Research Center

In May of 2021, the Insect Diagnostics program was brought back into service in an all-new digital format. Members of the public seeking assistance identifying an insect can access the Insect Diagnostics ID Request Form online. After providing observation information such as location and date of the sighting, followed by answering a set of questions intended to help with the identification process, one can then upload up to 3 photos and submit the form. The inquiry is then forwarded on to one of the entomology extension specialists. Within a few days, usually less than two, the identity of the insect along with appropriate life history information and/or control measures is then sent to the client by email or phone. The online submission process takes only a few minutes and can be accessed with desktop computers and mobile devices.

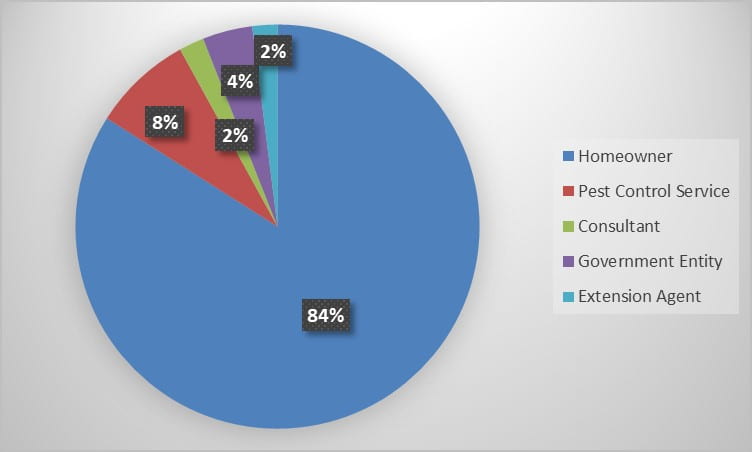

Between the initial launch in May and the end of September, Insect Diagnostics has processed 50 inquiries from 3 states. Kansas represented the majority of inquiries, but citizens of Colorado and Kentucky also utilized Insect Diagnostic’s services this year. Identification requests fell into several categories, from requests out of general curiosity to much more specific identification needs. The Home/Structural and General categories contained the bulk of this season’s inquiries (Figure 1). During the season, a variety of clientele reached out to our program for identification assistance. Homeowner’s submitted the most requests, followed by commercial pest control services (Figure 2). Government entities, independent agronomists and extension agents utilized our service as well.

Figure 1. Percent of total inquiries received for each request category during the 2021 season.

Figure 2. Percent of total inquiries received from each clientele category during the 2021 season.

While insects identified this season varied quite a bit, a few were more common in requests than others. Fall Armyworm was abundant in crops and lawns during the 2021 growing season and it showed up in requests frequently. As news outlets continued to report on the “Murder Hornets” in the Pacific Northwest, quite a few inquiries came in towards the end of summer for the unrelated, yet similar looking Cicada Killer wasp. Serious pests such as termites and bedbugs were identified several times and important control information was provided to the homeowners. Sometimes, inquiries were simply interesting insects that are not often observed, such as the Arkansas Clearwing moth (Figure 3.)

Figure 3. An Arkansas Clearwing Moth (Synanthedon arkansasensis). Photo by Jan Johnson, Shawnee Co.

The main season for insect activity may be coming to a close, but the Insect Diagnostics Program will continue to operate and accept online inquiries throughout the fall and winter. Insect Diagnostics would like to thank specialists Raymond Cloyd, Cassandra Olds, Jeff Whitworth and Frannie Miller for their contributions and expertise, which helped make the 2021 Insect Diagnostics reboot a success. If you need insect identification assistance, submit a request at https://entomology.k-state.edu/extension/diagnostician/.

Fall Armyworm – Second Generation

— by Raymond Cloyd — Horticultural Entomologist

Second-generation fall armyworm, Spodoptera frugiperda, caterpillars (larvae) are present throughout portions of Kansas. Those of you that have re-seeded your turfgrass should be on the lookout for the young caterpillars and take appropriate measures to prevent or minimize turfgrass damage.

Fall armyworm cannot survive exposure to freezing temperatures. Consequently, fall armyworm does not overwinter in Kansas, but can overwinter in mild climates such as southern Florida and Texas. The ability of fall armyworm to invade an area depends on prevailing weather conditions during the winter months in the regions where they overwinter. Cool, wet springs followed by warm, humid weather and abundant rainfall favor the movement of fall armyworm northward. Weather fronts are how fall armyworm moths disperse to other regions of the USA. Favorable conditions that can lead to massive infestations of fall armyworm include cool weather, abundant rainfall, well-managed turfgrass, and few natural enemies (e.g. parasitoids and predators). Fall armyworm outbreaks occur at irregular intervals throughout the USA.

Adult female and male moths (Figure 1) are typically active at night (nocturnal) and are attracted to lights. After mating, females lay gray, cottony egg masses on the surface of an assortment of objects or surfaces, including plant leaves, grass blades, twigs, windowpanes, and fence posts (Figure 2), sides of buildings, flag poles, golf carts, and decks. The number of eggs per mass is between 100 and 200 with up to 2,000 eggs laid per female. The eggs are covered by dense hairs resembling gray cotton or flannel. Caterpillars emerge (eclose) from eggs in two to four days at temperatures between 70 and 80°F (21 and 26°C). The higher temperatures lead to faster development.

Figure 1. Fall armyworm adult (Raymond Cloyd, KSU)

Picture not available —– Figure 2

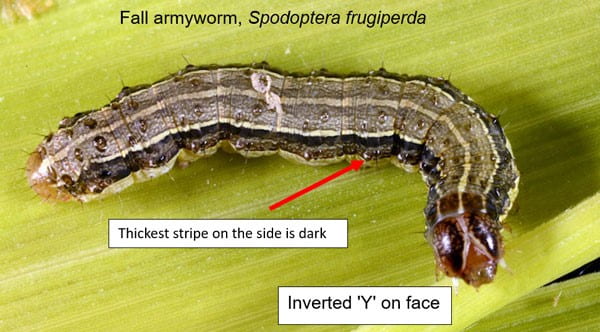

Caterpillars create silken strands, which allow them to reach the turfgrass. Early instar (young) caterpillars are 1/16 of an inch (2.0 mm) in length and light-green (Figure 3). Later instar (older) caterpillars are 1.5 inches (38 mm) long, tan to olive-green, with stripes that extend the length of both sides of the body (Figure 4). Fall armyworm caterpillars can be distinguished from true armyworm, Pseudaletia unipunctata, caterpillars by the presence of a light-colored, inverted Y-shaped marking on the front of the head (Figure 5). In addition, fall armyworm caterpillars have four black tubercles on the back of each abdominal segment.

Figure 3. Fall armyworm early instar caterpillar (Raymond Cloyd, KSU)

Figure 4. Fall armyworm later instar caterpillar (Raymond Cloyd, KSU)

Figure 5. Y-shaped marking on the head of fall armyworm caterpillar (Raymond Cloyd, KSU)

There are six larval instars. The first three instars feed on the underside of leaf blades, in leaf folds, or on the leaf margins resulting in a tattered appearance. The last three instars feed on leaf blades all the way down to the crown of the turfgrass resulting in extensive damage (Figure 6) in two to three days. At high densities, caterpillars will exhibit cannibalistic behavior—or eat each other.

Figure 6. Turfgrass damage caused by fall armyworm caterpillar feeding (Raymond Cloyd, KSU)

Caterpillars feed during the day and night. If disturbed, caterpillars will fall onto the soil surface and curl-up (Figure 7). If you look at the soil surface where the leaf blades have been chewed-down, you will notice piles of green frass or ‘caterpillar poop’ (Figure 8). Eventually, the sixth larval instar enters the soil and pupates in a silken webbing or cocoon at depths of 1.0 to 3.0 inches (2.5 to 7.6 cm). The soil depth that pupation occurs is contingent on soil texture, moisture, and temperature. Adult moths that emerge (eclose) from the pupae can live up to 21 days. The life cycle takes approximately four weeks to complete although development is dependent on temperature. Bermudagrass, Cynodon dactylon; tall fescue, Festuca arundinacea; and creeping bentgrass, Agrostis stolonifera, may be fed upon by fall armyworm caterpillars. There are one to two generations per year in Kansas.

Figure 7. Fall armyworm caterpillar curled-up on soil surface (Raymond Cloyd, KSU)

Figure 8. Fecal deposits or frass associated with fall armyworm caterpillar feeding (Raymond Cloyd, KSU)

There are no preventative treatments for fall armyworm. Consequently, when the young caterpillars are present, contact or stomach poison insecticides can be applied including those with the following active ingredients: azadirachtin, Bacillus thuringiensis subsp. kurstaki, bifenthrin, chlorantraniliprole, cyfluthrin, permethrin, lambda-cyhalothrin, and spinosad. Repeat applications of an insecticide may be needed depending on the extent of the infestation. However, check your turfgrass at least twice per week to determine if an insecticide application is warranted.

Bug Joke of the Week

–by Sharon Schroll

Q: What is a caterpillar scared of?

A: A dogerpillar!

Grasshoppers

–by Jeff Whitworth — Field Crops

Grasshoppers continue to be quite numerous in some alfalfa fields, and late-planted soybeans (see pic. 2). As these crops senesce or dry down, these grasshoppers sometimes move into wheat fields when the newly planted wheat starts to germinate where they can be a real hindrance to establishing a good stand.

Adult Grasshopper (there are many different kinds currently in the fields – this is a Differential Grasshopper) (pic by Cayden Wyckoff)

Stinkbugs

–Jeff Whitworth – Field Crops

Stinkbugs are still quite common this time of year and many are still nymphs (see pic. 1). Fortunately, most crops should be past the stage that might be susceptible to stinkbugs. Soybeans are probably the crop of most concern relative to stinkbugs. However, they seem to be very general feeders–sucking juice out of just about any juicy, succulent plant. Their relatively long, but somewhat fragile, mouthparts are used to pierce into plants to suck the fluid that they feed on. This is usually while the plants are actively growing and thus the epidermis is relatively tender or the mouthparts can’t penetrate. Thus, stinkbugs should not be a problem now relative to soybean yield, unless the soybeans are still in the early reproductive stages.

Picture 1: Stink Bug Nymph (pic by Cayden Wyckoff)

Fall armyworm infestations in early-planted wheat in central Kansas

–by J.P. Michaud — Entomologist, Agricultural Research Center, Hays, KS

There have been some heavy infestations of fall armyworms in early-planted wheat in Ellis County, with some plantings completely destroyed, and the larvae trying to finish up on the pigweeds. This is a very asynchronous, late generation of fall armyworm, with most larvae now almost mature, but some still quite small. Treatment will not be justified at this point. The best recommendation is to just wait until worms have finished feeding, recalling that larvae can “march” across to new fields after killing plants. If larvae are still active in adjacent fields, it will be best to wait until later in the planting window (up to 2nd week of October for Ellis County). The emerging moths should migrate south without laying any more eggs.

There have been many reports across the Midwest of large fall armyworm populations damaging crops, lawns and turf, so they are having a good year. There were some reports of true armyworms also. The color of these caterpillars is highly variable; the dark color depends on melanin deposition, which can increase at low temperatures, and the intensity of bright colors depends on plant pigments obtained in the diet. To help distinguish between these two worms, refer to the features identified in photos shown below.

Figure 1. Fall armyworm showing key identifying features. Photo by J. Obermeyer.

Figure 2. True armyworm with key identifying features. Photo by M. Spellman.

Bug Joke of the Week

–by Raymond Cloyd — Horticultural Entomology

Q: How Do Caterpillars Order The Latest Fashions?

A: Using Caterloges!

WORMS, WORMS, and MORE WORMS (army cutworms, fall armyworms)

–by Jeff Whitworth — Field Crops

2021 might be called the “year of the worm”. Starting in late winter/early spring, 2021, there was considerable activity by army cutworms. Most of the problem was caused by the larvae decimating thin strands of wheat and/or alfalfa. Then, since late spring/early summer, a combination of armyworms and fall armyworms have been causing serious concern and damage in lawns, pastures, and alfalfa fields throughout about the eastern 2/3rd’s of the state. Army cutworms spend the summer in the Rocky Mountains but start to migrate back into Kansas in early fall every year. The larvae may feed on just about any plants but mostly affect wheat and alfalfa, as these are usually the only plants actively growing this time of year. Armyworms, probably more so than fall armyworms, may continue to cycle through another generation or even two as they overwinter in Kansas, and thus it will probably take a “hard” frost or freeze to stop them. Fall armyworms, since they don’t usually overwinter in Kansas, may migrate south after this generation become adults-but there could be another, or at least partial generation. Armyworms infest primarily grasses, i.e. sorghum, corn, brome pastures, lawns, and often this time of year, wheat, but occasionally alfalfa, etc. Thus, if armyworms are the problem they could be around through another generation or maybe even two depending upon the weather. So, if armyworms are relatively small (see pic 1) they will probably feed for another 10-14 days then pupate (stop feeding). If they are relatively large (see pic 2) however, they will probably pupate in the next 3-7 days. There will probably be at least one more generation of armyworms. Fall armyworms (see pic 3) have a little wider host range, which includes alfalfa, soybeans, corn, sorghum, wheat, etc., but don’t usually overwinter in Kansas, thus, hopefully, will be heading south after these larvae finish feeding and become moths. Also, in the next 30-60 days army cutworm moths should have returned from their summer Rocky Mountain retreats to deposit eggs throughout at least the western 2/3rd’s of the state and thus, these tiny worms will start feeding on wheat and/or alfalfa all winter.

Picture 1: Small Armyworm (pic by Cayden Wyckoff)

Picture 2: Larger Armyworm (pic by Cayden Wyckoff)

Picture 3: Fall Armyworms (pic by Jay Wisbey)

New Extension Publications

–by Raymond Cloyd — Horticultural Entomology

Euonymus Scale: Insect Pest of Euonymus Plants Grown in Landscapes (MF3586 August 2021)

https://bookstore.ksre.ksu.edu/pubs/MF3586.pdf

Pollinators and Beneficial Insects (MF3588 September 2021)

https://bookstore.ksre.ksu.edu/pubs/MF3588.pdf