By Kansas Department of Agriculture.

The Kansas Department of Health and Environment and the Kansas Department of Agriculture are alerting the public to the first known occurrence of the Asian longhorned tick (ALHT), Haemaphysalis longicornis, in Kansas. KDHE identified the ALHT after it was found on a dog in Franklin County last week.

ALHT is an exotic, invasive tick species that was first identified in the United States in New Jersey in 2017. Since then, it has spread westward across the U.S. and, according to the U.S. Department of Agriculture, has now been documented in 21 states, with Kansas being the most recent (https://www.aphis.usda.gov/livestock-poultry-disease/cattle/ticks/asian-longhorned/asian-longhorned-tick-what-you-need-know).

“We have been monitoring the spread of the Asian longhorned tick, especially since it was confirmed in neighboring states,” said Kansas Animal Health Commissioner Dr. Justin Smith. “Now that it has been identified in Kansas, we have been in contact with accredited veterinarians across the state to remind them to be alert for this tick and to ensure they understand the risks.”

This prolific tick, which can reproduce without the need for a male tick, has both human and animal health implications. In 2019, an ALHT in Virginia was found to be infected with Bourbon virus, while Connecticut recently identified an ALHT infected with ehrlichiosis, both of which are tick-borne diseases that occur in Kansas but are currently transmitted by the Lone Star tick.

“We’re still learning about this tick and the ecologic role that it currently plays and may play in the future in terms of disease transmission to humans” Dr. Erin Petro, KDHE State Public Health Veterinarian, said. “While the human health implications are uncertain, this tick has serious implications for animal health.”

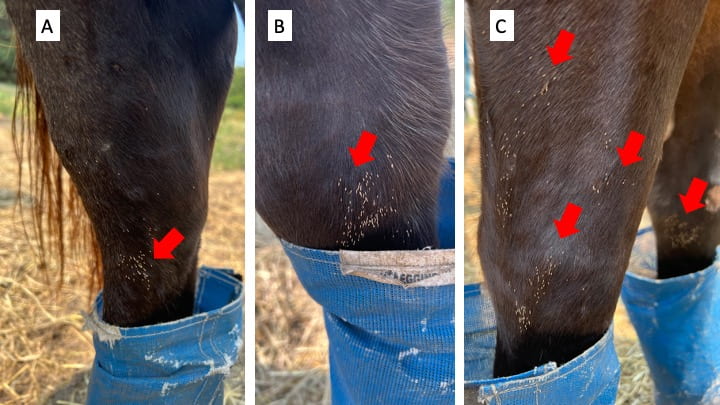

The ALHT can cause extreme infestations on affected animals, sometimes leading to severe anemia or even exsanguination. Beyond the physical threat, the ALHT also transmits the cattle parasite Theileria orientalis Ikeda strain, which causes bovine theileriosis.

In 2024, KDHE piloted a program to create a passive tick surveillance network of veterinary clinics throughout the state. Through this program, participating clinics submit tick samples from animals in their care to KDHE for identification. This program has been successful in providing information on where various ticks are found across the state and has been especially useful in under-surveyed areas. One of these partners submitted a routine sample which was later identified as ALHT by KDHE and confirmed by the USDA. In both humans and animals, tick bite prevention is key.

To reduce the risk of disease, follow these precautions:

- Be aware of where ticks are found and using preventive measures when in grassy, brushy, or wooded areas.

- Dress preventively by wearing long pants tucked into socks and shirt tucked into pants.

- Treat clothing and gear with permethrin.

- Use an EPA-approved repellent such as DEET, picaridin, or oil of lemon eucalyptus (OLE) when enjoying the outdoors or being in a tick habitat.

- After coming indoors, perform a thorough tick check, being sure to focus on the waistband, under the arms, in and around the ears, inside the belly button, back of knees, and in and around the hair.

- Check pets for ticks, especially around the tail, between the back legs, under the front legs, between the toes, in and around the ears, around the eyes, and under the collar.

- Shower soon after being in a tick habitat or engaging in outdoor activities. This will help remove any unattached ticks and identify any attached ticks.

- To remove attached ticks, use a pair of fine-tipped tweezers, grasp the tick near the skin, and apply gentle traction strait outwards until the tick is removed.

- Help prevent tick-borne diseases and tick infestations on pets by consulting with your veterinarian on use of a veterinary-approved flea and tick preventative.

- More information on tick bite prevention and controlling ticks in your environment can be found at Preventing Tick Bites | Ticks | CDC.

For more information on the Asian longhorned tick including where it has been found in the U.S., visit the USDA Longhorned Tick Story Map at https://www.aphis.usda.gov/livestock-poultry-disease/cattle/ticks/asian-longhorned/asian-longhorned-tick-what-you-need-know. To find more information on other ticks, their geographic distributions, and the diseases they transmit in Kansas, visit KDHE’s Tickborne Disease Data Stories at https://maps.kdhe.state.ks.us/kstbdhome/.

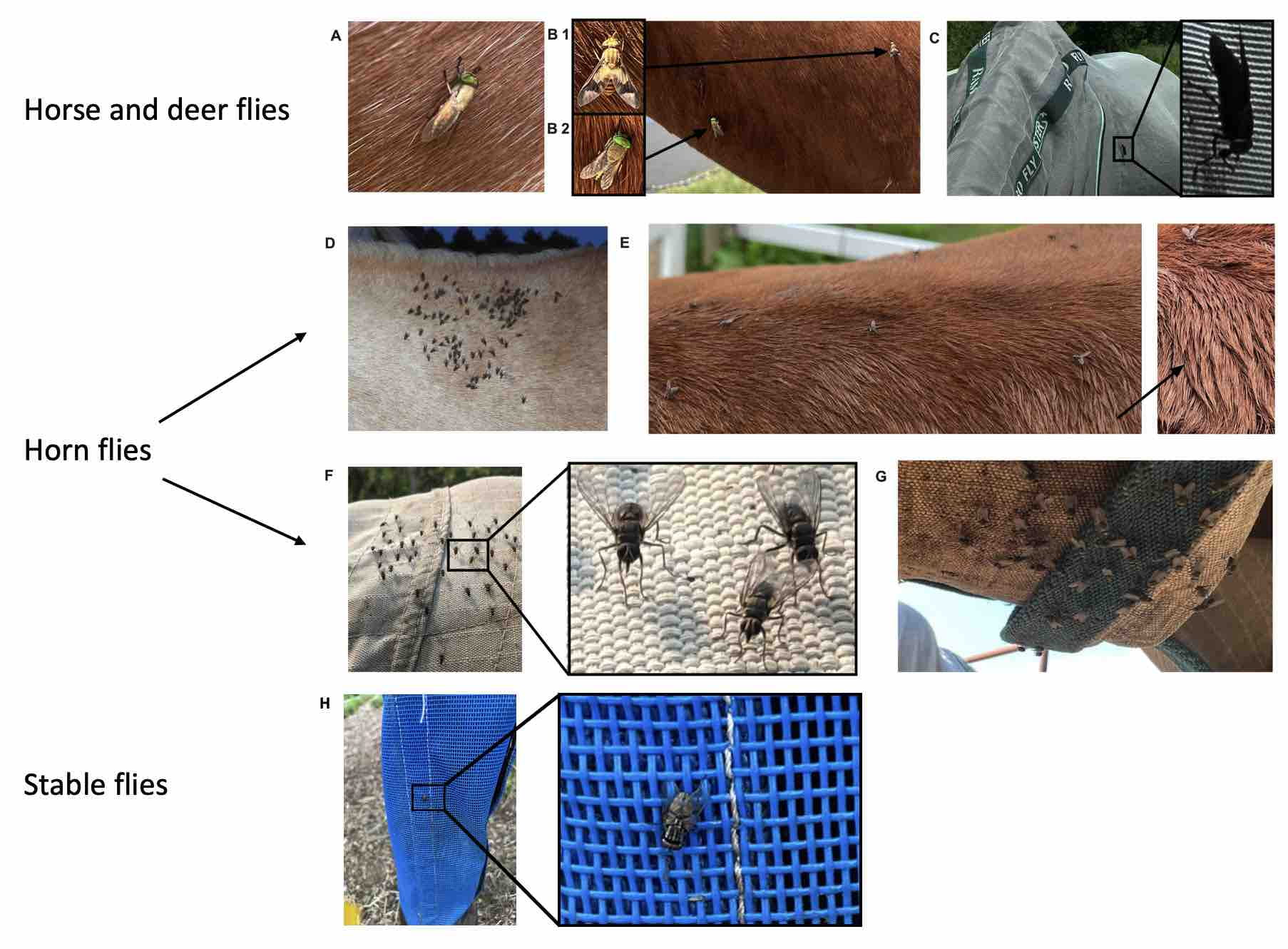

Dr. Cassandra Olds specializes in veterinary entomology and works with livestock producers, veterinarians and others through her extension efforts. For contact info and her lab: https://entomology.k-state.edu/about/people/faculty/Olds-Cassandra.html

Photo provided for the cover is courtesy of Joshua Jackson, entomology graduate student in the Olds Veterinary Entomology Lab.