–by Frannie Miller

Category: Household

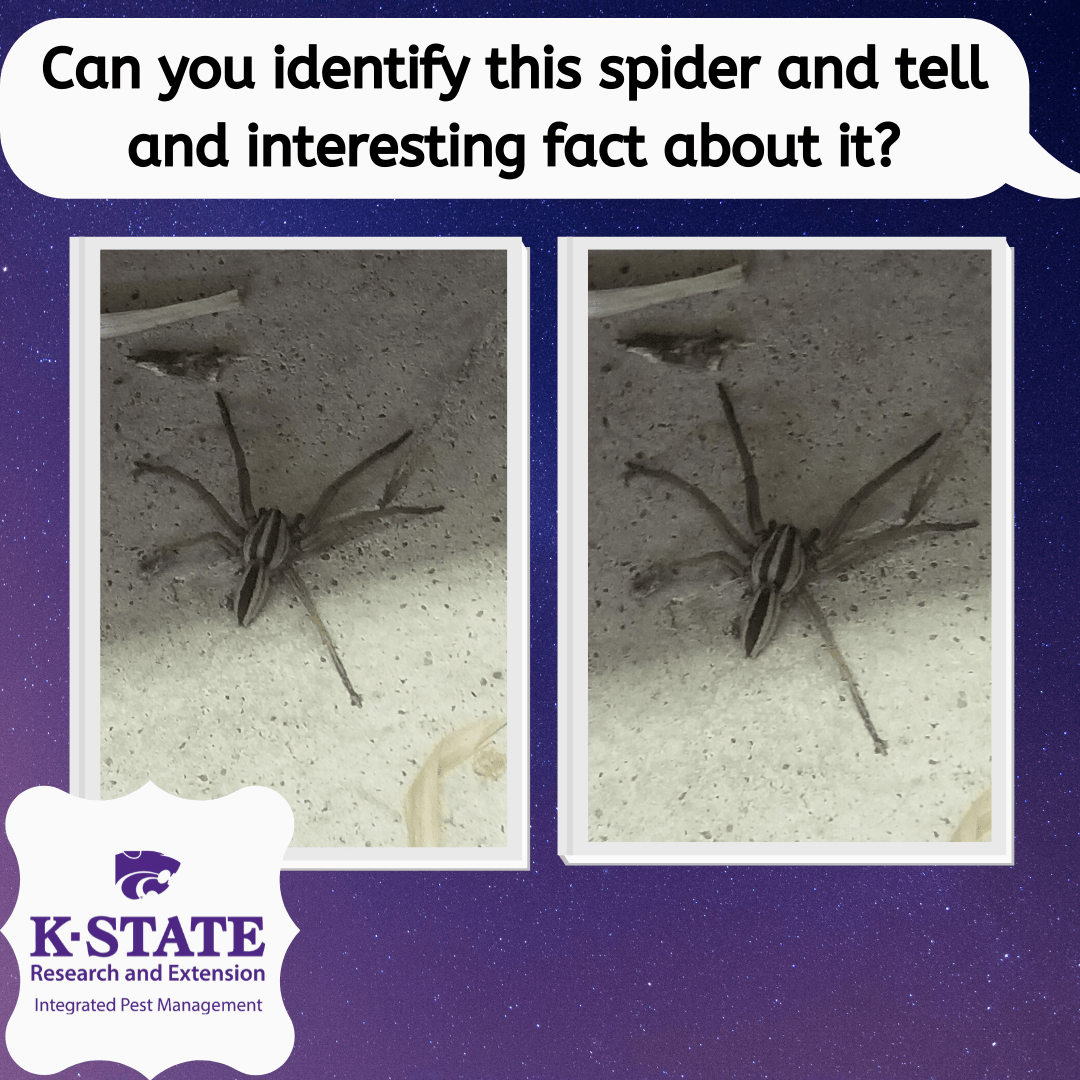

ID to last week’s bug

— by Frannie Miller

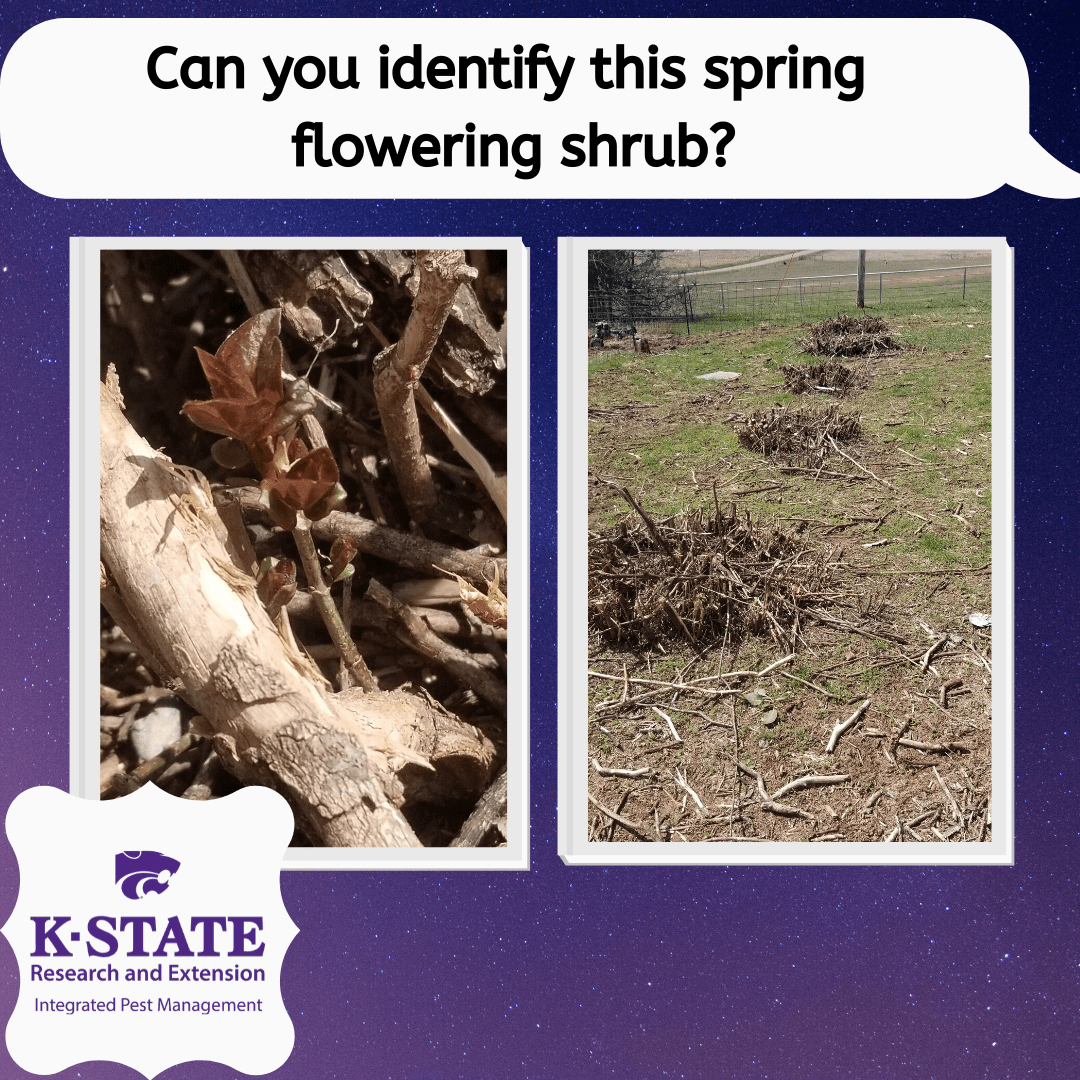

Lilacs – These are lilacs. Lilacs bloom on old wood, so I did not get to enjoy the blossoms this year. In this situation, our donkeys took a liking to them and decided to eat some of the bark, so they needed to be pruned to produce some new growth. Pruning is also an important practice if you have ash lilac borers.

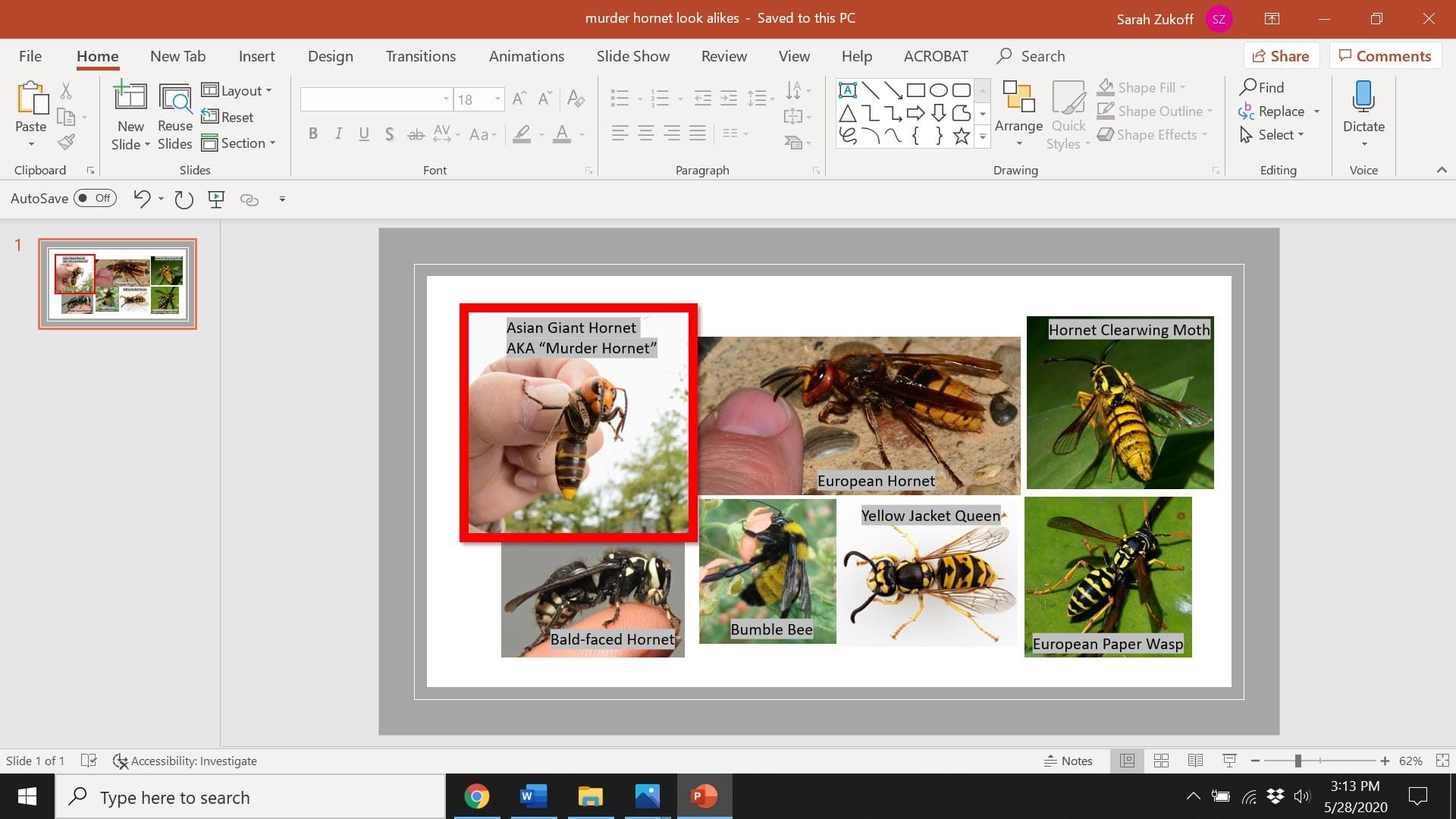

The Buzz about Asian Giant Hornets

–by Frannie Miller and Sarah Zukoff

The Asian Giant Hornet has created a buzz, since being found in the state of Washington/Canada border. These insects have been nicknamed “murder hornets” by the news media. It is important to remember none of these hornets have been found in the state of Kansas. These impressive hornets are similar to our US hornets in that they are not much more aggressive towards people unless their nest or food source is threatened. They do differ however by having a very potent, painful sting. Multiple stings by the Asian giant hornet would warrant medical attention even if the person were not allergic. The hornets build their nests each year underground in abandoned animal burrows or around the roots of trees making the nests hard to detect.

One cause for concern regarding their presence in the United States is their predatory nature towards honeybees. This hornet could devastate European honeybee colonies who have developed no defense mechanisms. Individual guard bees are no contest for the much larger hornet. Groups of hornets can go into a “slaughter phase” where they decimate an entire hive of bees. Then they will occupy the hive and feast upon the honeybee brood.

Japanese honey bees have developed a defensive mechanism to deal with the threat. They form a mass around the hornet and buzz their wings to create heat. The generated heat kills the hornet because the honeybees can survive at higher temperatures. Basically, a good depiction might be the thought of sticking the hornet in a honeybee microwave as illustrated in the cartoon.

Sadly, in all of the hysteria, many of our look-alike pollinators have been mistaken for the Asian Giant Hornet. Reports of panic killing of bumble bees, wasps, and others have been observed on various news and social media outlets.

The Asian Giant Hornet prefers mountainous valleys and has never been recorded from plains regions of any country. It has not been found in Kansas.

Identify This Insect

ID to last week’s bug

–by Frannie Miller

Snowy tree cricket – The image is of a snowy tree cricket. They are members of the order Orthoptera, which makes them more closely related to a grasshopper. They are sometimes referred to as “thermometer crickets” because you can estimate the temperature by counting the number of chirps for 15 seconds and adding 40.

Get Ready…Get Set…Go…Get Those Bagworms!

–by Dr. Raymond Cloyd

For those of you that have been waiting patiently by reading another book or counting your stockpile of toilet paper, or for some…impatiently, it is time to look for bagworms. Although the cool weather we have experienced this spring will slow development, and consequently larvae hatching from eggs, bagworm caterpillars will eventually be present throughout Kansas feeding on broadleaf and evergreen trees and shrubs. Therefore, be prepared to act against bagworms once observed on plants. Bagworms are primarily a pest of conifers; however, they feed on a wide-range of host plants including a number of broadleaf plants, such as; rose, honey locust, hackberry, and flowering plum. It is important to apply insecticides when bagworms are less than 1/4 inch long to maximize effectiveness of insecticide applications and subsequently reduce plant damage.

Several insecticides are labeled for use against bagworms including those with the following active ingredients: acephate, Bacillus thuringiensis subsp. kurstaki, cyfluthrin, lambda-cyhalothrin, trichlorfon, indoxacarb, chlorantraniliprole, and spinosad. Most of these active ingredients are commercially available and sold under various trade names or as generic products. However, several insecticides, however, may not be directly available to homeowners.

The key to managing bagworms with insecticides at this time of year is to apply insecticides early and frequently enough to kill the highly susceptible young caterpillars feeding on plant foliage (Figures 1 and 2). Applying insecticides weekly for four to five weeks when bagworms are first noticed will reduce problems with bagworms later in the year. The bacterium, Bacillus thuringiensis subsp. kurstaki, which sold under various trade names, is only active on young caterpillars and must be consumed or ingested to be

Fig 1. Young Bagworm Larva Or Caterpillar Feeding On Conifer (Auth–Raymond Cloyd, KSU)

Fig 2. Young Bagworm Larva Or Caterpillar Feeding On Plant Foliage (Auth–Raymond Cloyd, KSU)

effective. Therefore, thorough coverage of all plant parts and frequent applications are required. The insecticide is sensitive to ultra-violet light degradation and rainfall, which can reduce residual activity (persistence). Spinosad is the active ingredient in several homeowner products, including: Borer, Bagworm, Tent Caterpillar, and Leafminer Spray; Captain Jack’s DeadBug Brew; and Monterey Garden Insect Spray. The insecticide works by contact and ingestion; however, activity is greatest when ingested by bagworms.

Cyfluthrin, lambda-cyhalothrin, trichlorfon, chlorantraniliprole, and indoxacarb can also be used against young caterpillars. Again, thorough coverage of all plant parts, especially the tops of trees and shrubs, where bagworms commonly start feeding, and frequent applications are essential in achieving sufficient suppression of bagworm populations. The reason multiple applications are needed is that bagworm larvae do not hatch from eggs simultaneously, but hatch over time depending on temperature. In addition, young bagworms can ‘blow in’ (called ‘ballooning’) from neighboring plants on silken threads. If left unchecked, bagworms can cause significant damage and ruin the aesthetic quality of plants. In addition, bagworms may kill plants, especially newly transplanted small evergreens, since evergreens do not usually produce another flush of growth after being fed upon or defoliated by bagworms

If you have any questions on how to manage bagworms in your garden or landscape, contact your county horticultural agent, or university-based or state extension entomologist. You can also read the new extension publication on bagworms:

Cloyd, R. A. 2019. Bagworm: insect pest of trees and shrubs. Kansas State University

Agricultural Experiment Station and Cooperative Extension Service. Kansas State University; Manhattan, KS. MF3474. 4 pgs.

http://www.bookstore.ksre.ksu.edu/pubs/MF3474.pdf

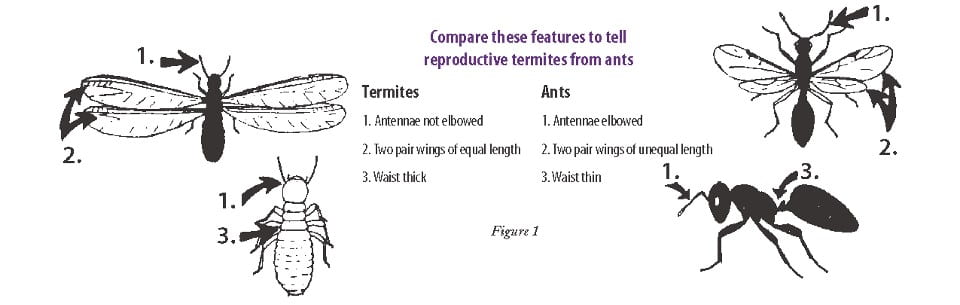

TERMITES

–by Dr. Jeff Whitworth

It seems termite swarming “season” is a little later than usual. However, they are now swarming in different parts of the state (fig. 4) (see picture from Sedgwick Co. on 20 May). Please remember to properly distinguish between ant swarmer’s vs. termite swarmer’s (fig. 5) (see diagram) as termite colonies are much more difficult (and expensive) to control then are ant colonies.

Figure 4 Termites swarming from a local business (20 May 2020)

Figure 5 Diagram comparing termites and ants

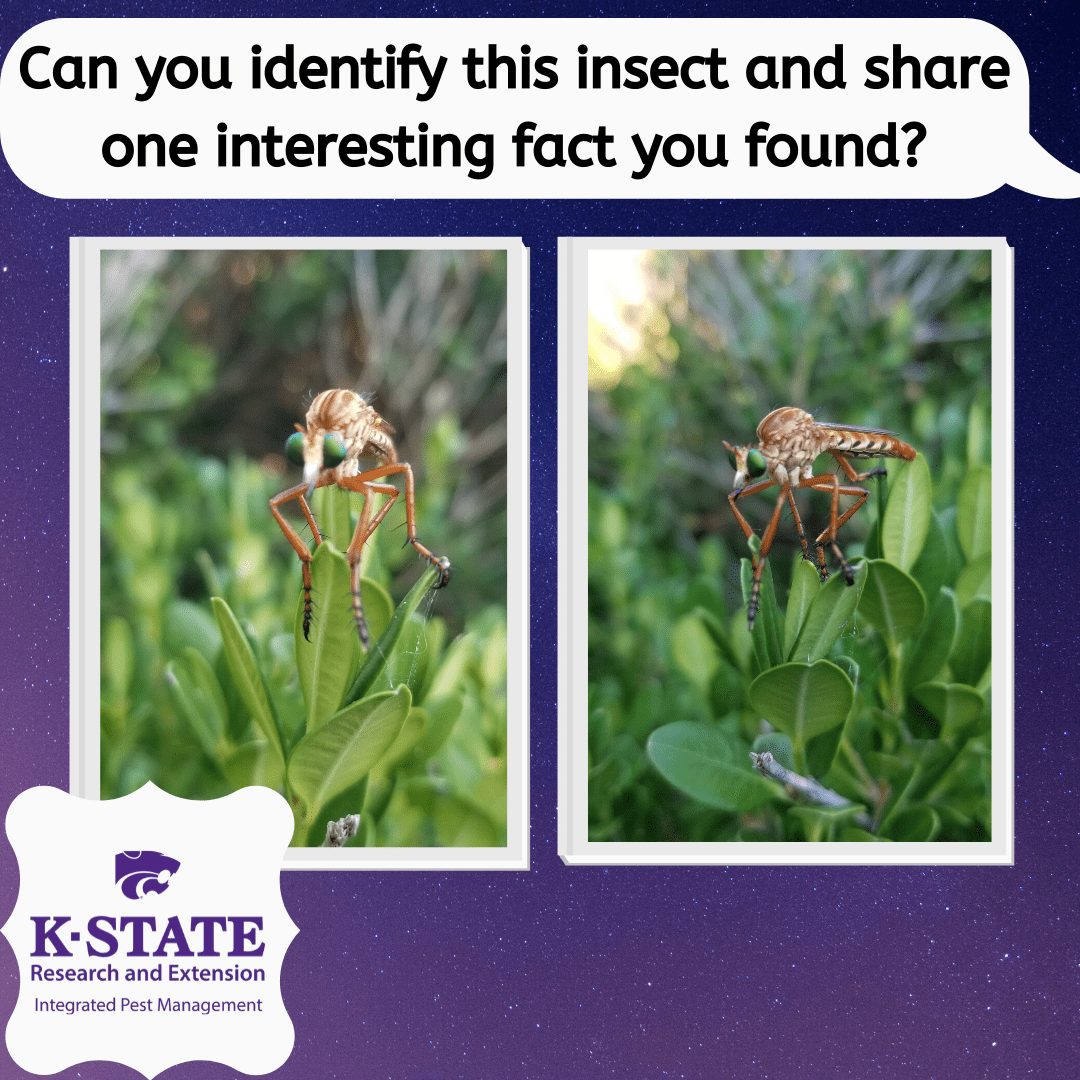

Identify This Insect

ID to last week’s bug

–by Frannie Miller

Robber Fly– This is an example of a robber fly. They are great predators and feed on a wide variety of arthropods, such as wasps, bees, grasshoppers etc. Robber flies have bristled, strong legs to help aid in catching prey.