–by Raymond Cloyd — Horticultural Entomology

Female mosquitoes (Figure 1) are out-and-about biting people outdoors to obtain a blood meal for reproduction (egg laying). The three primary strategies that should be implemented to avoid mosquito bites are: 1) source reduction, 2) personal protection, and 3) insecticides.

Figure 1. Mosquito Sucking Blood (Inverse)

1) Source Reduction

Eliminate all mosquito-breeding sites to reduce mosquito populations by removing stagnant or standing water from items or areas that may collect water, such as the following:

* Wheelbarrows

* Pet food or water dishes

* Saucers/dishes underneath flowerpots

* Empty buckets

* Tires

* Toys

* Wading pools

* Birdbaths

* Ditches

* Equipment

* In addition, check gutters regularly to ensure they are draining properly and are not

collecting water

2) Personal Protection

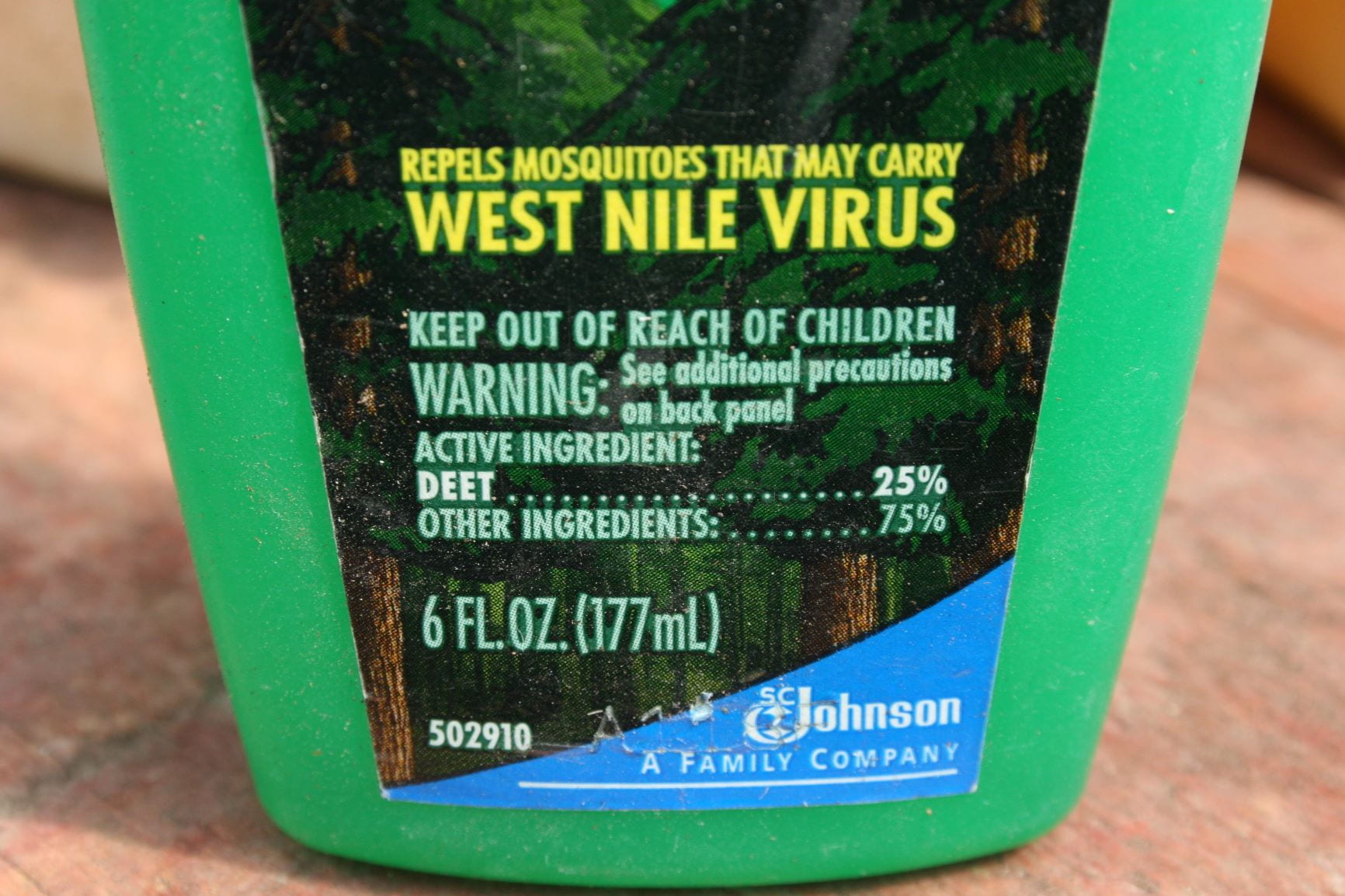

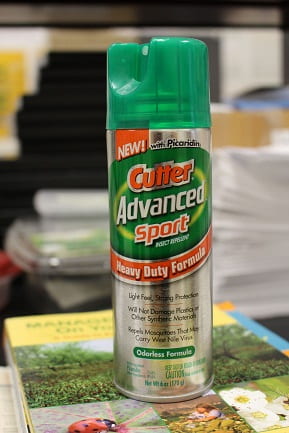

Protect yourself from mosquito bites by avoiding being outdoors during dawn or dusk when most mosquitoes are active. Repellents containing the following active ingredients: DEET (Figures 2 and 3) or picaridin (Figure 4) can be used. DEET, in general, provides up to 10 hours of protection whereas picaridin provides up to 8 hours of protection. A product with a higher percent of active ingredient will result in longer residual activity or repellency. For children, do not use any more than 30% active ingredient. In addition, do not use repellents on infants less than two months old. Clothing can be sprayed with DEET or permethrin, which is a pyrethroid-based insecticide. However, be sure to wash clothing separately afterward. Before applying any repellent, always read the product label carefully.

Figure 2. DEET Repellents (Raymond Cloyd, KSU)

Figure 3. DEET Repellents (Raymond Cloyd, KSU)

Figure 4. Repellent with Picaridin (Raymond Cloyd, KSU)

3) Insecticides

There are several products that may applied to stationary ponds, such as Mosquito Dunks and/or Mosquito Bits (Figure 5). Both contain the active ingredient, Bacillus thuringiensis subsp. israelensis, a bacterium that is ingested by mosquito larvae resulting in death. The bacterium only kills mosquito larvae with no direct effects to fish or other vertebrates. It is important to avoid making area-wide applications of contact insecticides because these are generally not effective, and may potentially kill many more beneficial insects and pollinators (e.g. bees) than mosquitoes.

Figure 5. Mosquito Dunks and Mosquito Bits (Raymond Cloyd, KSU)

What Does Not Work Against Mosquitoes

The following items are not effective in managing mosquito populations:

* Mosquito repellent plants (citronella plants)

* Bug zappers

* Electronic emitters

* Light traps/carbon dioxide traps.

If anyone has questions or comments regarding mosquito management, please contact your county extension office or Department of Entomology at Kansas State University (Manhattan, KS). For additional information on mosquitoes, I recommend the following publication:

Ortler, Brett. 2014. The Mosquito Book: An Entertaining, Fact-filled Look at the

Dreaded Pesky Bloodsuckers. Adventure Publications, Inc., Cambridge, MN.