–by Dr. Jeff Whitworth and Dr. Holly Schwarting

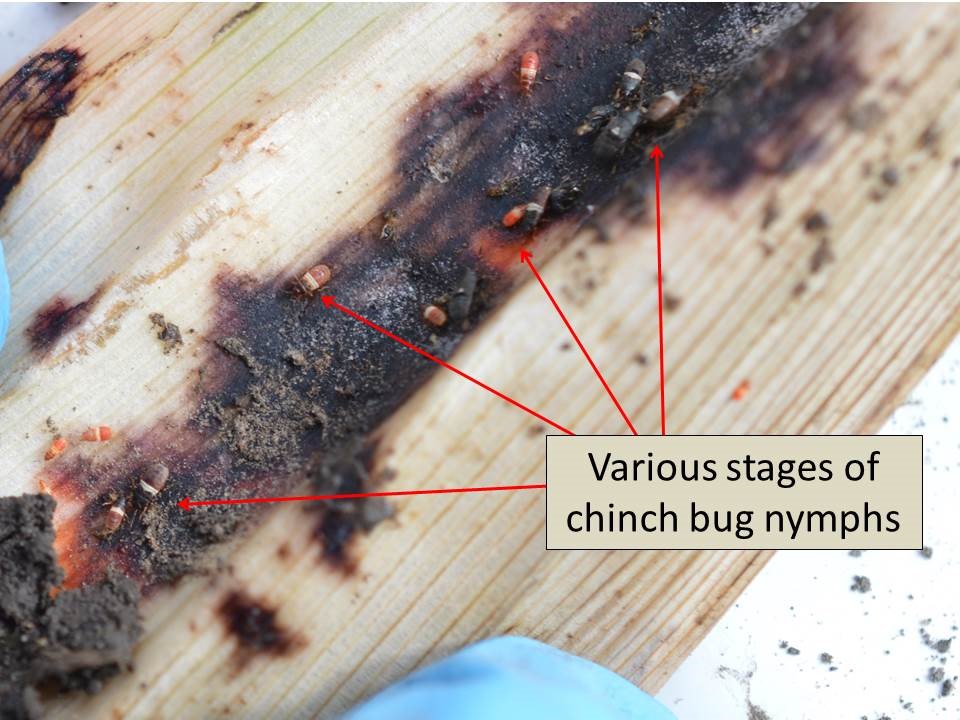

Chinch bugs continue to be very active in both corn and sorghum throughout north central Kansas. Both nymphs and adults are present.

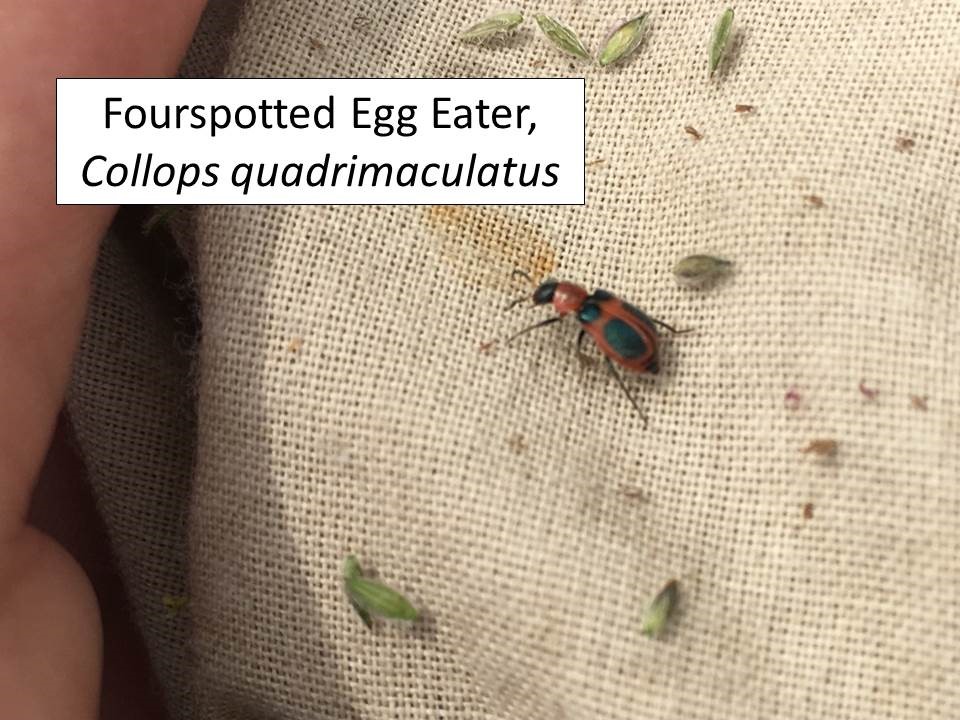

Many adults are still mating, which indicates that there are more eggs, nymphs, and adults yet to come. One consolation relative to the numerous chinch bugs in sorghum fields is that the four spotted egg eater, Collops quadrimaculatas, seems to be plentiful as well. They have been collected in samples while sweep sampling alfalfa and are also present in sorghum fields. These little beetles are predacious on insect eggs, and it has even been reported that they feed on chinch bug eggs. Not sure they will be able to provide a great deal of control on chinch bug populations but it sure can’t hurt!

Corn leaf aphids are also very plentiful throughout north central Kansas. These aphids usually feed on developing corn tassels and silks, but probably are more commonly associated with, or at least noticed in, whorl stage sorghum. These aphid colonies sometimes produce enough honeydew, and it is so sticky, that often the sorghum head gets bound up in the whorl and therefore doesn’t extend up properly. These colonies are not usually dense enough on a field-wide basis to justify and insecticide application. These plentiful aphids are also serving as a food source for many predators, i.e. lady beetles, green lacewings, etc.

Corn earworms are still plentiful in corn but as they mature, pupate, and become adults they most likely will migrate to sorghum to feed on developing kernels (between flowering and soft dough), and soybeans where they will feed on developing beans within the pods.

For more information on sorghum and soybean pest management, please consult the KSU Sorghum Insect Management guide: https://www.bookstore.ksre.ksu.edu/pubs/mf742.pdf

And the KSU Soybean Insect Management Guide: https://www.bookstore.ksre.ksu.edu/pubs/MF743.pdf