By Cody Domenghini, Assistant Professor, Landscape Management

A mulch ring is a circular border surrounding a tree commonly made of organic material such as wood chips. Trees planted in turfgrass should have mulch rings installed around them for a couple of reasons. Creating a mulch boundary around trees prevents lawn maintenance equipment such as string trimmers and mowers from getting too close to the trunk and causing damage. When grass is allowed to grow right up to the trunk the tree roots are in competition with the turfgrass for water and nutrients. A mulch layer over the root zone eliminates this conflict.

Ideally, trees should be planted in a landscape bed rather than in the middle of a lawn. However, when grown in a lawn, trees should have a mulch ring at least three feet in diameter for every inch of tree trunk caliper surrounding them.

The mulch should resemble the shape of a donut with the center of the ring creating a 4-6” gap between the trunk of the tree and the start of the mulch. The space between the tree trunk and the mulch ring allows oxygen and water to easily reach the roots and prevents the risk of rot at the base of the trunk.

Avoid the common mistake of “volcano mulching”. Layer the mulch 2-4” deep. Throughout the year the mulch will breakdown, contributing organic matter to the soil and improving soil quality. Mulch should be reapplied annually. When adding a tree ring to an already established tree in a lawn, carefully remove the sod from the top few inches to not damage any tree roots.

Mulch rings for large trees should be large enough to create a barrier between the edge of the turfgrass and the trunk of the tree to prevent damage to the trunk from mowing equipment, but do not necessarily have to follow the size guidelines advised for younger trees. Adding tree rings and mulch around trees is best done in the spring, but can be completed anytime of the year.

Below is a link to an extension article discussing the proper way to mulch trees.

https://www.johnson.k-state.edu/lawn-garden/agent-articles/trees-shrubs/how-to-mulch-trees.html

Rose rosette is currently showing up in Kansas gardens. This disease is a serious problem in wild multiflora roses but also goes to many common garden roses.

Rose rosette is currently showing up in Kansas gardens. This disease is a serious problem in wild multiflora roses but also goes to many common garden roses. leaves that stands out above the normal growth habit of the shrub. Reddish leaves are a tricky symptom because roses put out new flushes of growth throughout the growing season and the new leaves commonly start out red and then green up.

leaves that stands out above the normal growth habit of the shrub. Reddish leaves are a tricky symptom because roses put out new flushes of growth throughout the growing season and the new leaves commonly start out red and then green up. The larvae will fall onto the soil surface to pupate. Rose sawflies overwinter as pupae in earthen cells created by the larvae. There is typically one generation per year in Kansas. Rose sawfly larvae cause damage by feeding on the underside of rose leaves causing the leaves to appear skeletonized.

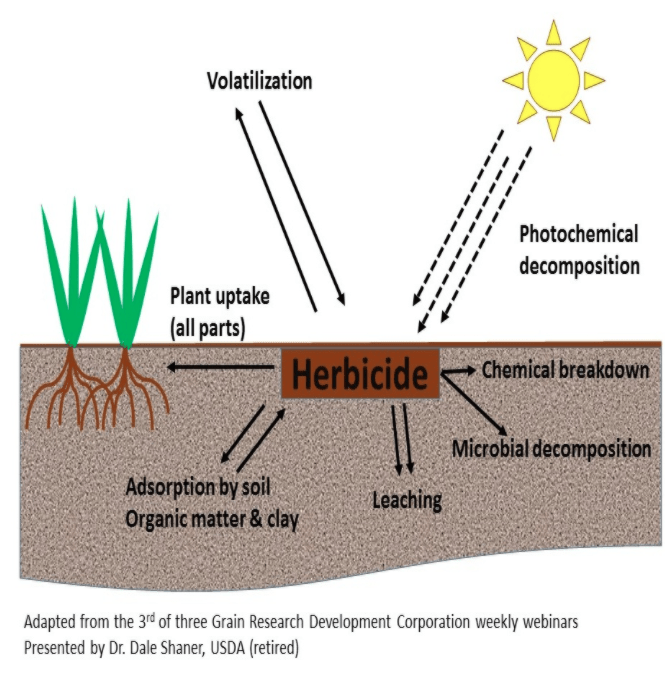

The larvae will fall onto the soil surface to pupate. Rose sawflies overwinter as pupae in earthen cells created by the larvae. There is typically one generation per year in Kansas. Rose sawfly larvae cause damage by feeding on the underside of rose leaves causing the leaves to appear skeletonized. Small infestations of rose sawflies are best dealt with by removing the larvae by hand and placing into a container of soapy water. A high pressure water spray will quickly dislodge sawfly larvae from rose plants. Once dislodged the larvae will not crawl back onto rose plants. There are contact insecticides containing various active ingredients that are effective in managing populations of sawflies. Sawflies are not caterpillars.

Small infestations of rose sawflies are best dealt with by removing the larvae by hand and placing into a container of soapy water. A high pressure water spray will quickly dislodge sawfly larvae from rose plants. Once dislodged the larvae will not crawl back onto rose plants. There are contact insecticides containing various active ingredients that are effective in managing populations of sawflies. Sawflies are not caterpillars.