–by Eva Zurek

Insect Diagnostic Laboratory Report

http://entomology.k-state.edu/extension/diagnostician/recent-samples.html

–by Eva Zurek

Insect Diagnostic Laboratory Report

http://entomology.k-state.edu/extension/diagnostician/recent-samples.html

–Dr. Bob Bauernfeind

Currently, we are only in mid-summer —- quite a ways away from consistently cool fall weather. Yet because we have had a couple days and evenings of unseasonably cool weather, people project forward and express concerns about spiders entering homes. And on my evening walks this past weekend, I noticed spiders resting on the roadway and in the gutters presumably soaking up the stored heat-of-the-day. These spiders are “hunters” (as opposed to webbing species – to be presented later) who are seeking prey. And hunting spiders are the types that are more likely to wander and roam and possibly/eventually enter homes later in the season.

There are various groups of hunting spiders. Unless people are especially observant, crab spiders (so named for their crab-like appearance and gait) escape detection due to their camouflaging ability, blending in to the background of the flower upon which they lay-in-wait to ambush unwary insects attracted to the flower. Given their habits, crab spiders are unlikely to enter homes.

Jumping spiders probably are more tolerated due to their non-menacing appearance. They are small (½ or less) and “cute” (colorful and somewhat fuzzy). They have a sort of herky-jerky walking motion. Jumping spiders are “visual hunters” and therefore possess quite large eyes which provide them with the visual acuity required to locate and leap/jump atop their prey. With a quick bite, they immobilize their prey. Occasionally jumping spiders enter homes. But because of the aforementioned traits, they tend to be regarded as “harmless”.

The anxiety when it comes to outdoor spiders entering homes usually applies to “wolf spiders”. Perhaps it is because of their name that the heebie-jeebies set in —- wolves bite so wolf spiders must automatically set out to bite (not so!). Perhaps it is because some of the many wolf spider species are large — body length in excess of 1¼-inches (I personally have never encountered one even reaching 1-inch). They may appear even larger given their long legs —- splayed out, spanning 3½ inches (that one I do have in a riker display). They are hairy (scarier than fuzzy). They are dark/sinister in appearance, being varying shades from brown to grey to black with some mottling — this coloration enabling them to blend into their habitat background and thus escape detection.

Wolf spiders are solitary hunters with excellent vision that is useful for detecting prey as they roam about. Some species create burrows where they lay-in-wait at the entrance, snatching prey that wander too close. Female wolf spiders attach and carry their egg sac to the spinnerets on the rear of their abdomen. When the spiderlings hatch, they climb on to their mothers backs who then carry them until they are ready to depart and be on their own.

Wolf spiders (like most spiders) tend to be shy and timid/non-aggressive. If provoked, they may deliver a justifiable “defensive bite”. However because their venom is mild, only redness, some swelling, mild pain and itching occur. Yet, if one wishes an added sense of relief, consult with and receive advice from a personal physician.

The following may seem like déjà vu. It isn’t. If you read Kansas Insect Newsletter #17 (two weeks ago), you saw much of the following text except that I have inserted the word spider for cricket.

The most successful approach for preventing spider “guests” is to EXCLUDE THEM! Spiders (as well as any other commonly named “fall guests” such as boxelder bugs, elm leaf beetles, multicolored Asian lady beetles, rollie pollies, crickets) gain entrance via any available crack/crevice/hole/gap. Attempt to insect-proof houses and buildings by thoroughly inspecting and identifying entry points. Check for cracks and gaps in structure foundations, ill-fitting doorways and garage doors, overhang louvers, chimney vents, roof ducts, soffits, air conditioner connections, outdoor faucets and siding. Use caulk to seal cracks and crevices, weather stripping to make doorways and garage doors tightfitting, and metal screening over/under/behind other entry points.

An oft-asked question is with regard to the effectiveness of barrier insecticide treatments around the outside perimeter a home. Although handbooks and manuals recommend such an approach, the wording is vague and noncommittal as to the effectiveness of such applications. I am not aware of any quantitative data validating the effectiveness of perimeter treatments. Given the speed and movement of spiders, I think it doubtful that they spend an adequate amount of time on a treated surface sufficient for insecticides to have effect.

*************************************

Aside from spiders entering homes/buildings, the other objection to their presence is just that — their mere presence. Fear of spiders is a learned response —- being raised in an environment where being fearful of spiders is taught.

Also, unsightly webbing is an aesthetic objection to the presence of spiders. We are at that time of year when spiders are becoming more evident. While spiderlings have been secretively feeding/growing/maturing throughout the summer (and webs were small and unobserved), now is when fully-grown females construct “noticeable” webs. Webs seemingly occur anywhere and everywhere. In bushes, lawns, gardens. Under eaves and other nooks and crannies of homes and buildings. Although there is no reason to do anything about webs, if people deem them to be unsightly, simply remove them.

For many years, my junipers and mugos have been home to funnel weavers.

Funnel weaving spiders themselves are secreted away in a tubular portion of their web where they await the arrival of a visitor. Vibrations sensed by the spider cause her to react by rushing out to capture her prey. You can bait a web and watch the action.

In lawns and other low grassy areas, similar “sheets” of webbing are also made by sheetweb weavers. These spiders wait beneath the webbing and bite their victims from below, after which they are pulled through the sheet where they are then consumed.

A third category of spiders (orb-weavers) produce beautiful symmetric webs designed to ensnare intruders which (by chance) happen by. There are many species of orb weavers. No one description fits all. Some have a daily routine of constructing temporary webs. With the approach of sunrise, “used silk” is taken

down/gathered and consumed. With the approach of evening dark, she constructs her new web, recycling the silk from her previous web. Others orb weavers construct permanent webs which require repair from time to time.

Depending on the species, some orb weavers hide by day. If you encounter an in-tact orb web during daylight hours, the web’s owner usually can be located nearby, perhaps in a curled up leaf or in some out-of-way concealed location. Or, if you know where an orb weaver has its “nightly web”, during the day, you can find her “snoozing away” as she awaits night’s return.

Others (such as the golden garden spider) do not hide during the day. Rather, they are continually present, positioning themselves head-down in the central hub of their web. This offers ample opportunity for people/kids to “interact” with them. Especially interesting is the speed with which a spider detects and instantly moves towards her prey, and the dexterity and speed with which she enwraps her catch. She will then feed at her leisure. When no longer of food value (“sucked dry”), she will cut loose her depleted prey to then simply drop to the ground.

Webbing spiders are opportunistic generalist feeders. Whatever blunders into a web becomes a meal. If the victim happens to be regarded as a pest species such as the ensnared grasshopper (above) or a male bagworm moth (to the right), we think,

“GREAT!”

If the captured insect is (in of itself) considered a beneficial insect (a praying mantid), we utter,

Awww. Geez.”

But again, spiders are opportunists regardless of how we might view their victims.

The capture/demise of individual insect pests might be used by some individuals as evidence/proof to point to and express, “See? Spiders are important for biological control!” While hypothetical calculations have been used to extoll the benefits of spiders as biological control entities, in truth, such expectations likely are unrealistic. Again, because spiders are indiscriminate feeders, they are not “pest specialists”. Additionally, not being socially adept (rather, viewing any neighboring kin as “food”), spider populations are not sufficiently dense to accomplish meaningful biological control of insect species deemed “pests”. This being said, allow them their existence and space. Simply, respect them for their beauty and fascinating habits.

An update on my spider friends? As of today (as I write this), the landscape people are busy at my home. I expect to see a very different picture when I arrive home after work. My original 1993 plantings will be gone —- so no more “home sites” for my spider friends.

–by Dr. Jeff Whitworth and Dr. Holly Schwarting

Sorghum headworm (corn earworm, fall armyworm) populations continue to cause much concern throughout south central and north central Kansas. Sorghum is most vulnerable to headworms from flowering to soft dough. The general rule is that headworms may cause 5% loss per worm per head during the approximately 2 weeks the worms are feeding directly on the grain. So early detection, while the larvae are small, is always recommended, and thus if treatment is justified, control will be achieved before maximum damage is realized. For more information on sorghum headworm and control options, please visit: http://entomology.k-state.edu/extension/insect-information/crop-pests/sorghum/cornearworm.html

–by Dr. Jeff Whitworth and Dr. Holly Schwarting

Soybean aphids were detected in north central Kansas on 21 August (see photo). These aphids have been observed every year since 2002, when they were first detected in Kansas, but have rarely reached populations that stressed plants. Double cropped fields just reaching reproductive stages could be most susceptible if these populations increase. Probably the easiest way to find soybean aphid colonies that are just starting is to look for ants on soybean plants (see photo). If you sweep net soybean canopies and find ants in your sweep net, this indicates there are aphids in the field. Ants are phenomenal at finding these aphids when they are just beginning to produce honeydew. Or, if you are scouting plants and see ants on the plants, again, that indicates that soybean aphids are nearby producing the honeydew that ants are interested in. For more information on the soybean aphid, please visit: http://entomology.k-state.edu/extension/insect-information/crop-pests/soybeans/sba/

–by Dr. Jeff Whitworth and Dr. Holly Schwarting

Alfalfa continues to cause concern throughout north central and south central Kansas due to defoliation by “worms”. There seems to be a combination of garden (alfalfa) webworms, fall armyworms, armyworms, yellow striped armyworms, etc. feeding on the foliage. Generally, if the alfalfa is within 10 days of swathing or if the “worms” are mature, (maybe ½ inch long for webworms which are naturally smaller than the others; or ¾ inch long for the others), it probably is best to just cut the field and not treat. If treatment is justified, please pay attention to the pre harvest interval (PHI) for whatever product is used. These worms won’t feed on the foliage after it is cut, but they may feed under the windrows holding back the regrowth and causing striping in these fields. For more information on these insects and their control options, as well as PHI’s, please visit: http://www.bookstore.ksre.ksu.edu/pubs/MF809.PDF

Mississippi State just released some very good preliminary data on the efficacy of Transform and Sivanto for sugarcane aphid control during cool temperatures. Cooler temps (<60F) slow the aphids activity down and they do not feed as much and are not taking the product up as fast. For maximum efficacy, apply these two chemicals during the hottest part of the day especially during cooler days.

http://www.mississippi-crops.com/2015/08/24/sugarcane-aphid-control-with-falling-temperatures/

-Sarah Zukoff

Discovery of Rusty Plum Aphid, Hysteroneura setariae (Thomas), in Southwestern Kansas

As if cereal farmers didn’t have enough to worry about with the explosion of sugarcane aphid in sorghum and recent reports of the hedgehog grain aphid, Sipha maydis, New Mexico, Colorado and Missouri. Last week, samples of a reddish-brown aphid were collected from sorghum in mixed infestations of sugarcane aphid, Melanaphis sacchari, and corn leaf aphid, Rhopalosiphum maidis. Specimens were identified by Dr. Susan Halbert (Dept. of Plant Industry, Florida) as rusty plum aphid, Hysteroneura setariae (Thomas). The aphids were discovered in a dryland sorghum field just north of a grassy pasture in Stevens county.

The host range of this aphid is quite broad and includes grasses in the genera Cynodon, Eragrotis, Eleusine, Hordeum, Oryza, Panicum, Pennisetum, Saccharum, Setaria, Sorghum and Triticum. Thus, it has the potential to infest wheat, sorghum, barley, millet and sugarcane; it is a recognized pest of rice in Asia and Africa. Plants in the family Cyperaceae (sedges), cocconut seedlings, peanut and papaya have also been reported as hosts. Direct feeding damage to plants appears limited to sap removal, and it may have greater economic importance as a vector of many plant viruses including sugarcane mosaic potyvirus, cucumber mosaic, watermelon mosaic 2, papaya ringspot, and zucchini yellow mosaic.

The rusty plum aphid is capable of sexual reproduction (and thus overwintering in the egg stage) wherever trees of the genus Prunus are present, although it can also remain asexual on cereals year-round in warm climates. It has been found in North America for many years, primarily in California and Florida, and as far north as Minnesota and several northeast states, but very little is known about its biology or its potential to attain pest status the High Plains cereal crops.

The key features for identifying rusty plum aphid are the first 3 antennal segments that, along with the tibia (lower leg), are very pale, almost colorless, with the distal segments of these appendages shading to black. The cornicles (‘tailpipes’) are long and uniformly dark and the cauda (tail) is pale.

-Sarah Zukoff and J.P. Michaud

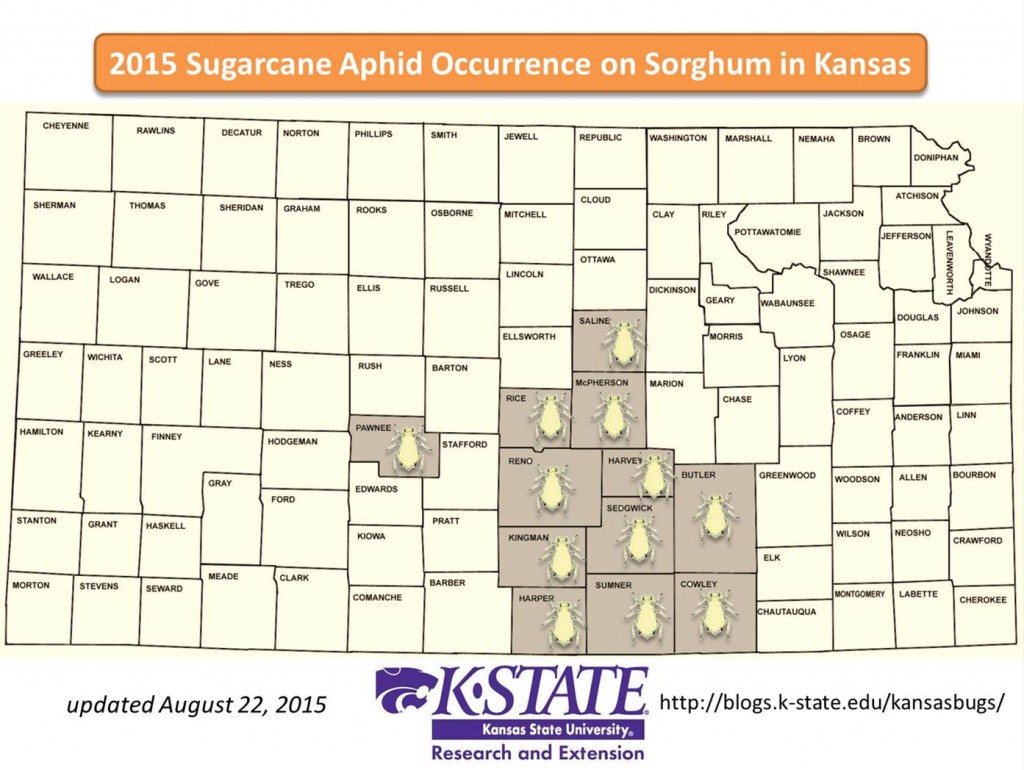

The sugarcane aphid continues to spread in Kansas sorghum and has now reached as far west as Haskell county and as far north as Dickinson county. In addition to these counties, the SCA was discovered in Edwards county today. Populations are low in these counties so far, but fields in these areas should be monitored closely. Contact your local extension agent if you discover the SCA or if you need help identifying aphids in your sorghum.

The sugarcane aphid on sorghum continues to move northward from south central Kansas. Recent winds have brought flights of other aphids as well. Of these, light colored corn leaf aphid and light colored greenbugs tend to be the aphids that are most confused with the sugarcane aphids (see below). The nymphs can be especially hard to differential without a magnification.

The sugarcane aphid on sorghum continues to move northward from south central Kansas. Recent winds have brought flights of other aphids as well. Of these, light colored corn leaf aphid and light colored greenbugs tend to be the aphids that are most confused with the sugarcane aphids (see below). The nymphs can be especially hard to differential without a magnification.

Greenbugs have dark feet, dark antennae, but light colored cornicles (tail pipes). Greenbugs will often have a green stripe down their backs, but this can be hard to see in light colored aphids. The sugarcane aphid also has dark feet and darker antennae, however it has dark cornicles and no green stripe down its back.

Thresholds have recently changed for the sugarcane aphid. See here for the latest threshold and scouting information for Kansas.

For information on chemical options, see the “Insecticide Selection for Sorghum at Risk to Sugarcane Aphids” from Texas A&M.

-Dr. Sarah Zukoff

–by Eva Zurek

Insect Diagnostic Laboratory Report

http://entomology.k-state.edu/extension/diagnostician/recent-samples.html