Time to Fertilize Warm-Season Grasses

June is the time to fertilize warm-season lawn grasses such as bermudagrass, buffalograss, and zoysiagrass. These species all thrive in warmer summer weather, so this is the time they respond best to fertilization. The most important nutrient is nitrogen (N), and these three species need it in varying amounts.

Bermudagrass requires the most nitrogen. High-quality bermuda stands need about 4 lbs. nitrogen per 1,000 sq. ft. during the season (low maintenance areas can get by on 2 lbs.). Apply this as four separate applications, about 4 weeks apart, of 1 lb. N per 1,000 sq. ft. starting in early May. It is already too late for the May application, but the June application is just around the corner. The nitrogen can come from either a quick- or slow-release source. So any lawn fertilizer will work. Plan the last application for no later than August 15. This helps ensure the bermudagrass is not overstimulated, making it susceptible to winter-kill.

Zoysiagrass grows more slowly than bermudagrass and is prone to develop thatch. Consequently, it does not need as much nitrogen. In fact, too much is worse than too little. One and one-half to 2 pounds N per 1,000 sq. ft. during the season is sufficient. Split the total in two and apply once in early June and again around mid-July. Slow-release nitrogen is preferable but quick-release is acceptable. Slow-release nitrogen is sometimes listed as “slowly available” or “water insoluble.”

Buffalograss requires the least nitrogen of all lawn species commonly grown in Kansas. It will survive and persist with no supplemental nitrogen, but giving it 1 lb. N per 1,000 sq. ft. will improve color and density. This application should be made in early June. For a little darker color, fertilize it as described for zoysiagrass in the previous paragraph, but do not apply more than a total of 2 lb. N per 1,000 sq. ft. in one season. Buffalograss tends to get weedy when given too much nitrogen. As with zoysia, slow-release nitrogen is preferable, but fast-release is also OK. As for all turfgrasses, phosphorus and potassium are best applied according to soil test results because many soils already have adequate amounts of these nutrients for turfgrass growth. If you need to apply phosphorus or potassium, it is best to core aerate beforehand to ensure the nutrients reach the roots.

Thatch Control in Warm-Season Lawns

Thatch control for cool-season lawn grasses such as bluegrass and tall fescue is usually done in the fall but now is the time we should perform this operation for warm-season turfgrasses such as bermudagrass and zoysiagrass. Because these operations thin the lawn, they should be performed when the lawn is in the best position to recover. For warm-season grasses that time is June through July. Buffalograss, our other common warm-season grass, normally does not need to be dethatched.

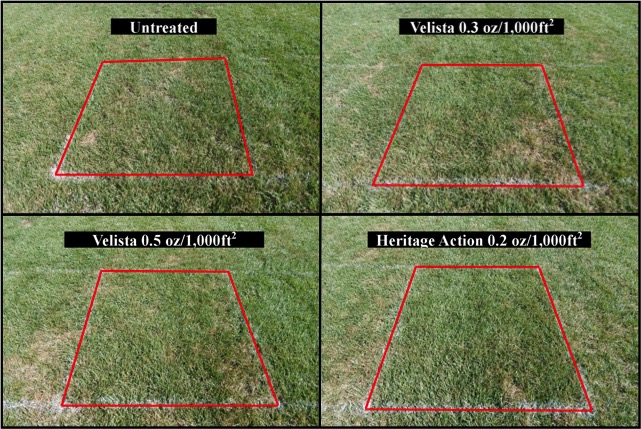

When thatch is less than one-half inch thick, there is little cause for concern; on the contrary, it may provide some protection to the crown (growing point) of the turfgrass. However, when thatch exceeds one-half inch in thickness, the lawn may start to deteriorate. Thatch is best kept in check by power-raking and/or core-aerating. If thatch is more than 3/4 inch thick, the lawn should be power-raked. Set the blades just deep enough to pull out the thatch. The lawn can be severely damaged by power-raking too deeply. In some cases, it may be easier to use a sod cutter to remove the existing sod and start over with seed, sprigs or plugs. If thatch is between one-half and a 3/4- inch, thick, core-aeration is a better choice.

The soil-moisture level is important to do a good job of core-aerating. It should be neither too wet nor too dry, and the soil should crumble fairly easily when worked between your fingers. Go over the lawn enough times so that the aeration holes are about 2 inches apart. Excessive thatch accumulation can be prevented by not overfertilizing with nitrogen. Frequent, light watering also encourages thatch. Water only when needed, and attempt to wet the entire root zone of the turf with each irrigation.

Finally, where thatch is excessive, control should be viewed as a long-term, integrated process (i.e., to include proper mowing, watering, and fertilizing) rather than a one-shot cure. One power-raking or core-aeration will seldom solve the problem.