By Chandler Day, Associate Diagnostician, K-State Plant Disease Diagnostic Lab

A quality diagnoses starts with a quality sample. A sample can be physical plants or digital images of plants. Digital images are a great screening tool to determine if a physical sample is required for diagnoses. In order to make a diagnosis, the quality of the images and/or samples is extremely important. Follow these tips for submitting your plant health questions. If you ever have questions about a plant problem, how to collect and/or ship a sample, feel

free to call or email us.

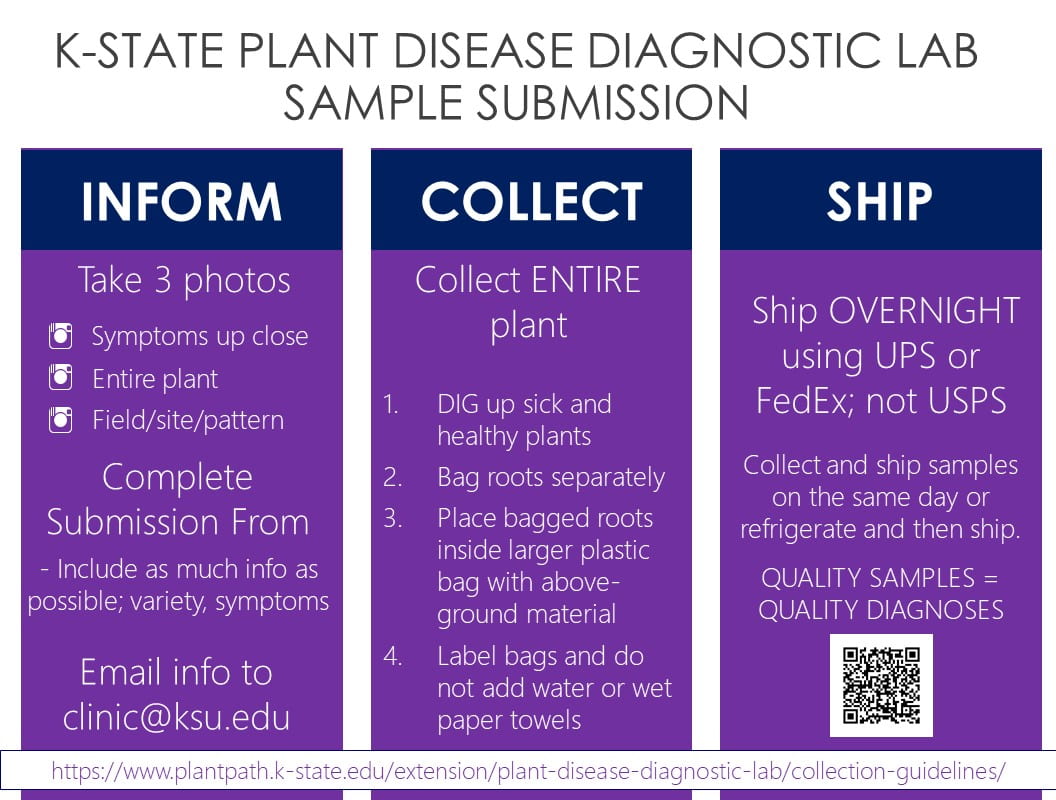

Inform. Collect. Ship.

Inform:

Send photos and background information to clinic@ksu.edu!

Three types of high quality digital images are an excellent way to pre-screen plant health issues.

- Symptoms up close (Fig. 1)

- Take zoomed in photos of the problem/symptoms.

- Ensure the image is in focus by tapping the image before you take the shot.

- Examples of symptoms: leaf spot, branch die-back, sunken tissue, scorched leaves.

- Entire plant. (Fig. 2.)

- Take photos of the entire plant that includes all plant parts from soil level to the top of the plant.

- Ensure the symptoms are still visible in this type of image.

- Example: whole tree or shrub (trunk/base to top of crown).

- Landscape pattern. (Fig. 3.)

- Stand back and capture the entire landscape where the plant resides.

- Include in the photo the surrounding plants, concrete, rocks, drain spouts, or whatever else is near the symptomatic plant. Don’t worry if the symptoms cannot be seen in this type of image.

- The importance of this image is not to capture the symptoms on the plant but to capture the landscape. This gives us look at how the affected plant is growing within the site and if there are any site issues that might be contributing to the problem.

Useful background information:

- Site history:

- Soil types, drainage, slope, sunny or shady problem areas, previous construction activity, proximity to structures such as roads or sidewalks, etc.

- Irrigation practices:

- Frequency of irrigation, length of time, irrigation application method (sprinkler, drip, hand held hose), time of day

- Chemical history:

- Pesticide usage and timing, fertilizer applications, etc.

- Pattern on plant:

- Describe the problem. Are symptoms on new or old growth? Top or bottom of plant?

- Pattern in landscape:

- One host or multiple hosts? Other plants in the landscape showing similar symptoms?

- Timing:

- When did the symptoms occur: All at once? (i.e. after a storm?) Slowly over time?

Collect:

- Complete the sample submission form with as much information as possible.

- Send a “healthy” plant and a “sick” plant.

- Submit entire plants when possible including roots. (EX. Tomatoes, annuals, turf grass, etc.)

- DIG up plants. Do NOT pull up plants as this can damage the roots.

- Bag roots separately and then place entire plant into larger plastic bag.

- Do NOT add water or use paper bags. These degrade the sample quality and affects the diagnostic process.

- For specific collection guidelines, go to the K-State Plant Disease Diagnostic Lab webpage, scroll down to where it says collection tips, and use the arrows on the right hand side to navigate to the appropriate collection strategy.

Ship:

- Collect and ship samples on the same day. If this is not possible, store plants in plastic bags in the refrigerator until shipping is possible.

- Ship plants overnight using UPS or FedEx. UPS can take up to 14 days even with 2 day priority shipping.

- Ship on or before Wednesday to avoid weekend storage.

The K-State Plant Disease Diagnostic Lab is here to help you identify your plant health problems. If you ever have questions about a plant problem, how to collect and/or ship a sample, feel free to call or email us.

K-State Plant Disease Diagnostic Lab

4032 Throckmorton PSC

1712 Claflin Road

Manhattan, KS 66506

clinic@ksu.edu

785-532-6176

Rose rosette is currently showing up in Kansas gardens. This disease is a serious problem in wild multiflora roses but also goes to many common garden roses.

Rose rosette is currently showing up in Kansas gardens. This disease is a serious problem in wild multiflora roses but also goes to many common garden roses. leaves that stands out above the normal growth habit of the shrub. Reddish leaves are a tricky symptom because roses put out new flushes of growth throughout the growing season and the new leaves commonly start out red and then green up.

leaves that stands out above the normal growth habit of the shrub. Reddish leaves are a tricky symptom because roses put out new flushes of growth throughout the growing season and the new leaves commonly start out red and then green up.